Financing Secrets Of A Millionaire Real Estate Investor

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in

regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the pub-

lisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If

legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent pro-

fessional person should be sought.

Vice President and Publisher: Cynthia A. Zigmund

Editorial Director: Donald J. Hull

Senior Managing Editor: Jack Kiburz

Interior Design: Lucy Jenkins

Cover Design: Design Alliance, Inc.

Typesetting: Elizabeth Pitts

2003 by William Bronchick

Published by Dearborn Trade Publishing

A Kaplan Professional Company

All rights reserved. The text of this publication, or any part thereof, may not be repro-

duced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

030405060710987654321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bronchick, William.

Financing secrets of a millionaire real estate investor / William

Bronchick.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-7931-6820-1

(

7.25

×

9 pbk.)

1. Mortgage loans—United States. 2. Secondary mortgage

market—United States. 3. Real property—United States—Finance. 4.

Real estate investment—United States—Finance. I. Title.

HG2040.5.U5B767 2003

332.7

′

22—dc21

2003000057

Dearborn Trade books are available at special quantity discounts to use for sales pro-

motions, employee premiums, or educational purposes. Please call our Special Sales

Department, to order or for more information, at 800-621-9621, ext. 4404, or e-mail

trade@dearborn.com.

v

C

ONTENTS

1. Introduction to Real Estate Financing

1

Understanding the Time Value of Money 2

The Concept of Leverage 2

Owning Property “Free and Clear” 5

How Financing Affects the Real Estate Market 6

How Financing Affects Particular Transactions 7

How Real Estate Investors Use Financing 8

When Is Cash Better Than Financing? 9

What to Expect from This Book 10

Key Points 10

2. A Legal Primer on Real Estate Loans

11

What Is a Mortgage? 11

Promissory Note in Detail 12

The Mortgage in Detail 14

The Deed of Trust 15

The Public Recording System 15

Priority of Liens 16

What Is Foreclosure? 17

Judicial Foreclosure 17

Nonjudicial Foreclosure 18

Strict Foreclosure 19

Key Points 19

3. Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

21

Institutional Lenders 21

Primary versus Secondary Mortgage Markets 22

Mortgage Bankers versus Mortgage Brokers 23

Conventional versus Nonconventional Loans 25

Conforming Loans 25

Nonconforming Loans 28

vi

CONTENTS

Government Loan Programs 28

Federal Housing Administration Loans 29

The Department of Veterans Affairs 30

State and Local Loan Programs 31

Commercial Lenders 31

Key Points 32

4. Working with Lenders 33

Interest Rate 33

Loan Amortization 34

15-Year Amortization versus 30-Year Amortization 36

Balloon Mortgage 37

Reverse Amortization 38

Property Taxes and Insurance Escrows 38

Loan Costs 39

Origination Fee 39

Discount Points 39

Yield Spread Premiums: The Little Secret Your Lender

Doesn’t Want You to Know 39

Loan Junk Fees 40

“Standard” Loan Costs 41

Risk 44

Nothing Down 45

Loan Types 46

Choosing a Lender 48

Length of Time in Business 49

Company Size 50

Experience in Investment Properties 50

How to Present the Deal to a Lender 51

Your Credit Score 52

Your Provable Income 56

The Property 56

Loan-to-Value 58

The Down Payment 59

Income Potential and Resale Value of the Property 60

Financing Junker Properties 60

Refinancing—Worth It? 61

Filling Out a Loan Application 61

Key Points 62

CONTENTS

vii

5. Creative Financing through Institutional Lenders

63

Double Closing—Short-Term Financing without Cash 63

Seasoning of Title 65

The Middleman Technique 67

Case Study #1: Tag Team Investing 69

Case Study #2: Tag Team Investing 70

Using Two Mortgages 71

No Documentation and Nonincome Verification Loans 72

Develop a Loan Package 75

Subordination and Substitution of Collateral 76

Case Study: Subordination and Substitution 77

Using Additional Collateral 79

Blanket Mortgage 79

Using Bonds as Additional Collateral 80

Key Points 82

6. Hard Money and Private Money

83

Emergency Money 83

Where to Find Hard-Money Lenders 84

Borrowing from Friends and Relatives 85

Using Lines of Credit 86

Credit Cards 86

Key Points 87

7. Partnerships and Equity Sharing

89

Basic Equity-Sharing Arrangement 90

Scenario #1: Buyer with Credit and No Cash 90

Scenario #2: Buyer with Cash and No Credit 91

Your Credit Is Worth More Than Cash 91

Tax Code Compliance 92

Pitfalls 93

Alternatives to Equity Sharing 93

Joint Ventures 94

Using Joint Venture Partnerships for Financing 94

Legal Issues 95

Alternative Arrangement for Partnership 95

Case Study: Shared Equity Mortgage with Seller 96

When Does a Partnership Not Make Sense? 97

Key Points 98

viii

CONTENTS

8. The Lease Option

99

Financing Alternative 100

Lease—The Right to Possession 100

Sublease 100

Assignment 100

More on Options, the “Right” to Buy 101

An Option Can Be Sold or Exercised 102

Alternative to Selling Your Option 102

The Lease Option 103

The Lease Purchase 103

Lease Option of Your Personal Residence 104

The Sandwich Lease Option 106

Cash Flow 107

Equity Buildup 107

Straight Option without the Lease 108

Case Study: Sandwich Lease Option 109

Sale-Leaseback 110

Case Study: Sale-Leaseback 111

Key Points 112

9. Owner Financing

113

Advantages of Owner Financing 115

Easy Qualification 115

Cheaper Costs 116

Faster Closing 116

Less Risk 116

Future Discounting 117

Assuming the Existing Loan 117

Assumable Mortgages 117

Assumable with Qualification 118

Buying Subject to the Existing Loan 118

Risk versus Reward 119

Convincing the Seller 120

A Workaround for Down-Payment Requirements 121

Installment Land Contract 122

Benefits of the Land Contract 124

Problems with the Land Contract 125

Using a Purcahse Money Note 125

Variation: Create Two Notes, Sell One 126

Another Variation: Sell the Income Stream 126

CONTENTS

ix

Wraparound Financing 127

The Basics of Wraparound Financing 127

Wraparound versus Second Mortgage 130

Mirror Wraparound 132

Wraparound Mortgage versus Land Contract 133

Key Points 133

10. Epilogue

135

Appendix A Interest Payments Chart 139

Appendix B State-by-State Foreclosure Guide 141

Appendix C Sample Forms 143

Uniform Residential Loan Application

[

FNMA Form 1003

]

144

Good Faith Estimate of Settlement Costs 148

Settlement Statement

[

HUD-1

]

149

Note

[

Promissory—FNMA

]

151

California Deed of Trust

(

Short Form

)

153

Mortgage

[

Florida—FNMA

]

155

Option to Purchase Real Estate

[

Buyer-Slanted

]

171

Wrap Around Mortgage

[

or Deed of Trust

]

Rider 173

Installment Land Contract 174

Subordination Agreement 176

Glossary 179

Resources 187

Suggested Reading 187

Suggested Web Sites 188

Real Estate Financing Discussion Forums 188

Index 189

1

CHAPTER

1

Introduction to Real

Estate Financing

Knowledge is power.

—Francis Bacon

In 1991, I made my first attempt at financing an investment prop-

erty through creative means. With a lot of guts and a little knowledge,

I made an offer that was accepted by the seller. I tendered $1,000 as

earnest money on the sales contract, then proceeded to try to make

the deal work. I failed, lost my $1,000, but I learned an important les-

son—a little knowledge can be dangerous. I decided then to become a

master at real estate finance.

Financing has traditionally been, and will always be, an integral

part of the purchase and sale of real estate. Few people have the funds

to purchase properties for all cash, and those that do rarely sink all of

their money in one place. Even institutional and corporate buyers of

real estate use borrowed money to buy real estate.

This book explains how to utilize real estate financing in the

most effective and profitable way possible. Mostly, this book focuses

on acquisition techniques for investors, but these techniques are also

applicable to potential homeowners.

2

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Understanding the Time Value of Money

In order to understand real estate financing, it is important that

you understand the time value of money. Because of inflation, a dollar

today is generally worth less in the future. Thus, while real estate val-

ues may increase, an all-cash purchase may not be economically feasi-

ble, because the investor’s cash may be utilized in more effective ways.

The cost of borrowing money is expressed in interest payments,

usually a percent of the loan amount. Interest payments can be calcu-

lated in a variety of ways, the most common of which is simple inter-

est. Simple interest is calculated by multiplying the loan amount by the

interest rate, then dividing it up into period

(

12 months, 15 years, etc

)

.

Example:

A $100,000 loan at 12% simple interest is $12,000

per year, or $1,000 per month. To calculate monthly simple-

interest payments, take the loan amount

(

principal

)

, multiply

it by the interest rate, and then divide by 12. In this example,

$100,000 × .12 = $12,000 per year ÷ 12 = $1,000 per month.

Mortgage loans are generally not paid in simple interest but

rather by amortization schedules

(

discussed in Chapter 4

)

, calculated

by amortization tables

(

see Appendix A

)

.

Amortization,

derived from

the Latin word “amorta”

(

death

)

, is to pay down or “kill” a debt. Amor-

tized payments remain the same throughout the life of the loan but are

broken down into interest and principal. The payments made near the

beginning of the loan are mostly interest, while the payments near the

end are mostly principal. Lenders increase their return and reduce

their risk by having most of the profit

(

interest

)

built into the front of

the loan.

The Concept of Leverage

Leverage

is the process of using borrowed money to make a re-

turn on an investment. Let’s say you bought a house using all of your

cash for $100,000. If the property were to increase in value 10 percent

☛

1 / Introduction to Real Estate Financing

3

The Federal Reserve and Interest Rates

The Federal Reserve

(

the Fed

)

is an independent

entity created by an Act of Congress in 1913 to

serve as the central bank of the United States.

There are 12 regional banks that make up the Fed-

eral Reserve System. While the regional banks are

corporations whose stock is owned by member

banks, the shareholders have no influence over the

Federal Reserve banks’ policies.

Among other things, the function of the Fed is

to try to regulate inf lation and credit conditions in

the U.S. economy. The Federal Reserve banks also

supervise and regulate depository institutions.

So how does the Fed’s policy affect interest

rates on loans? To put it simply, by manipulating

“supply and demand.” The Fed changes the money

supply by increasing or decreasing reserves in the

banking system through the buying and selling of

securities. The changes in the money supply, in

turn, affect interest rates: the lower the supply of

money, the higher the interest rate that is charged

for loans between banks. The more it costs a bank

to borrow money, the more they charge in interest

to consumers to borrow that money. The preced-

ing is a simplified explanation, because there are

other factors in the world economy that affect

interest rates and money supply. And, of course,

there are also widely varying opinions by econo-

mists as to what factors drive the economy and

interest rates.

4

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

over 12 months, it would now be worth $110,000. Your return on in-

vestment would be 10 percent annually

(

of course, you would actually

net less because you would incur costs in selling the property

)

.

Equity = Property value – Mortgage debt

If you purchased a property using $10,000 of your own cash and

$90,000 in borrowed money, a 10 percent increase in value would

still result in $10,000 of increased equity, but your return on cash is

100 percent

(

$10,000 investment yielding $20,000 in equity

)

. Of

course, the borrowed money isn’t free; you would have to incur loan

costs and interest payments in borrowing money. However, by rent-

ing the property in the meantime, you would offset the interest

expense of the loan.

Let’s also look at the income versus expense ratios. If you pur-

chased a property all cash for $100,000 and collected $1,000 per

month in rent, your annual cash-on-cash return is 12 percent

(

simply

divide the annual income, $12,000, by the amount of cash invested,

$100,000

)

.

If you borrowed $90,000 and the payments on the loan were

$660 per month, your annual net income is $4,080

(

$12,000 –

[

$660

× 12

])

, but your annual cash-on-cash return is about 40 percent

(

annual cash of $4,080 divided by $10,000 invested

)

.

Calculating Return on Investment

Annual return on investment

(

ROI

)

is the interest

rate you yield on your cash investment. It is calcu-

lated by taking the annual cash flow or equity

increase and dividing it by the amount of cash

invested.

1 / Introduction to Real Estate Financing

5

So, if you purchased ten properties with 10 percent down and

90 percent financing, you could increase your overall profit by more

than threefold. Of course, you would also increase your risk, which

will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

Owning Property “Free and Clear”

For some investors, the goal is to own properties “free and clear,”

that is, with no mortgage debt. While this is a worthy goal, it does not

necessarily make financial sense. See Figure 1.1.

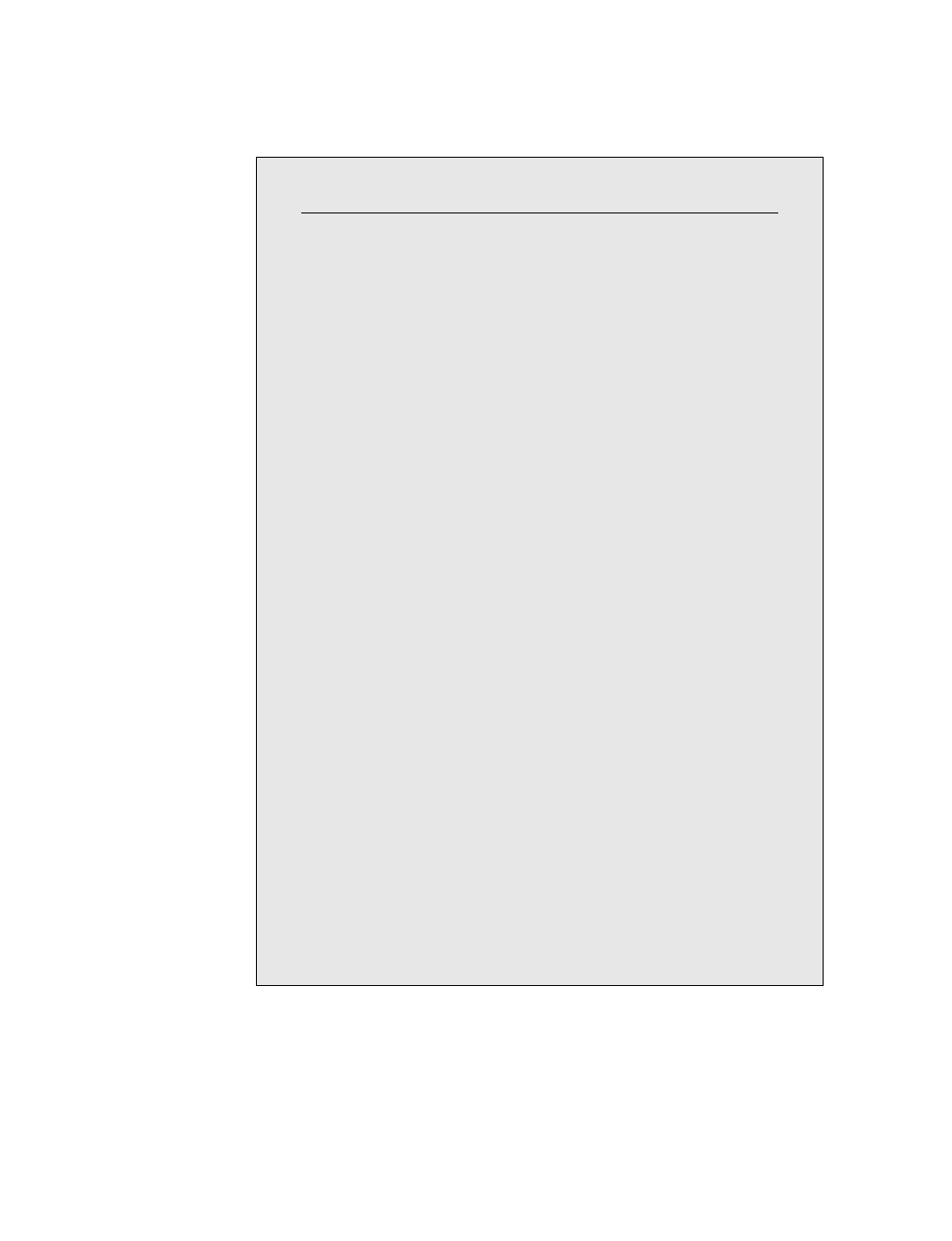

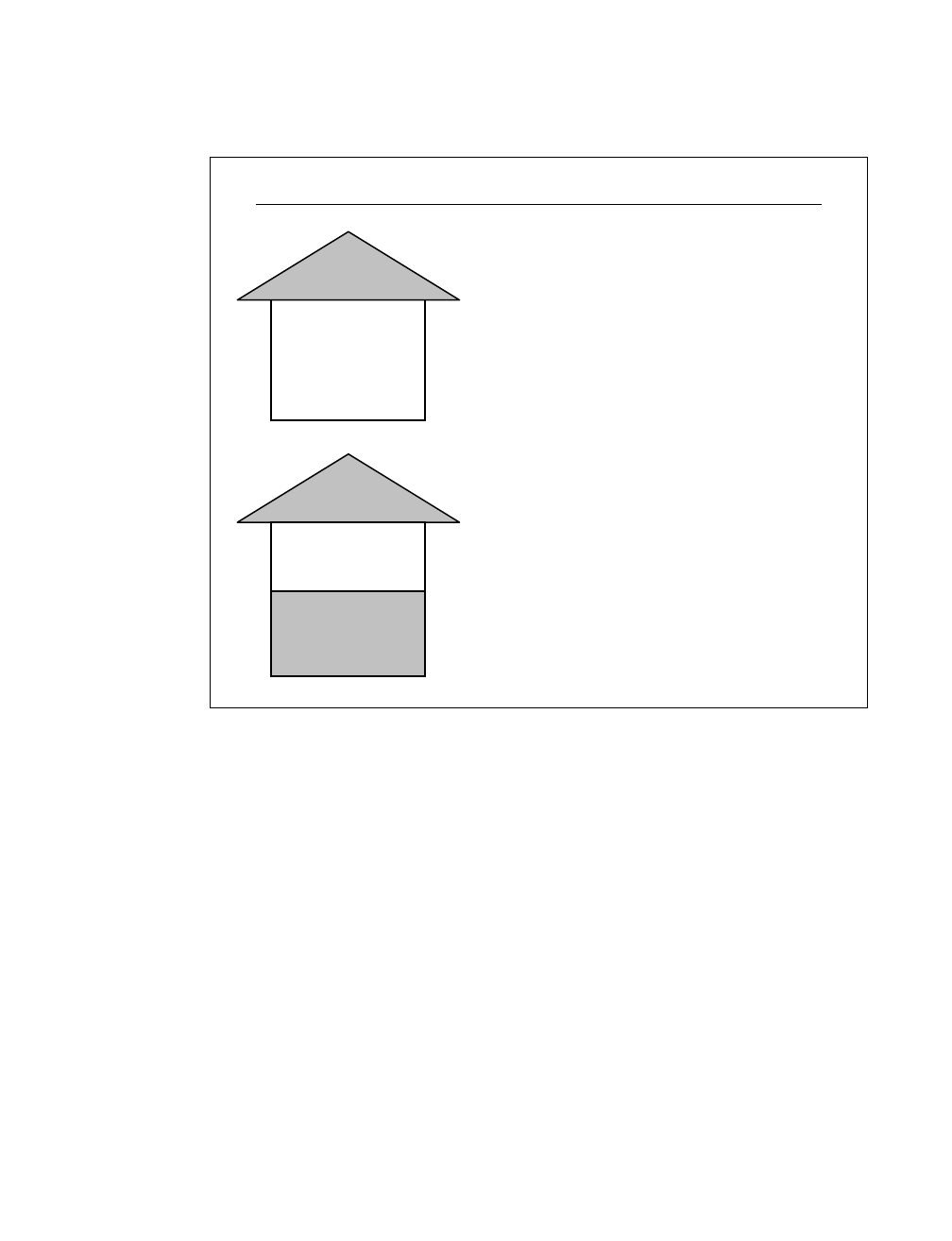

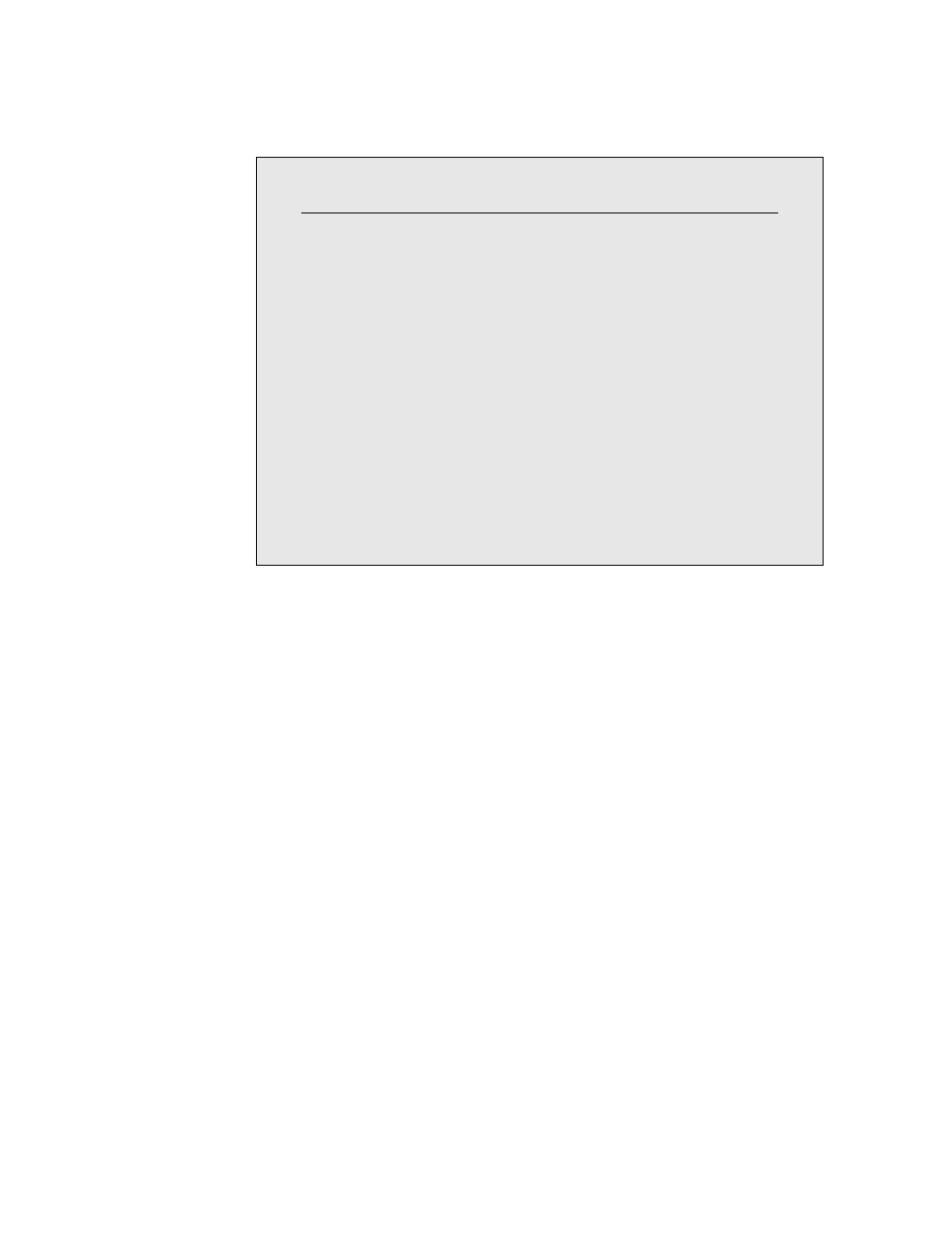

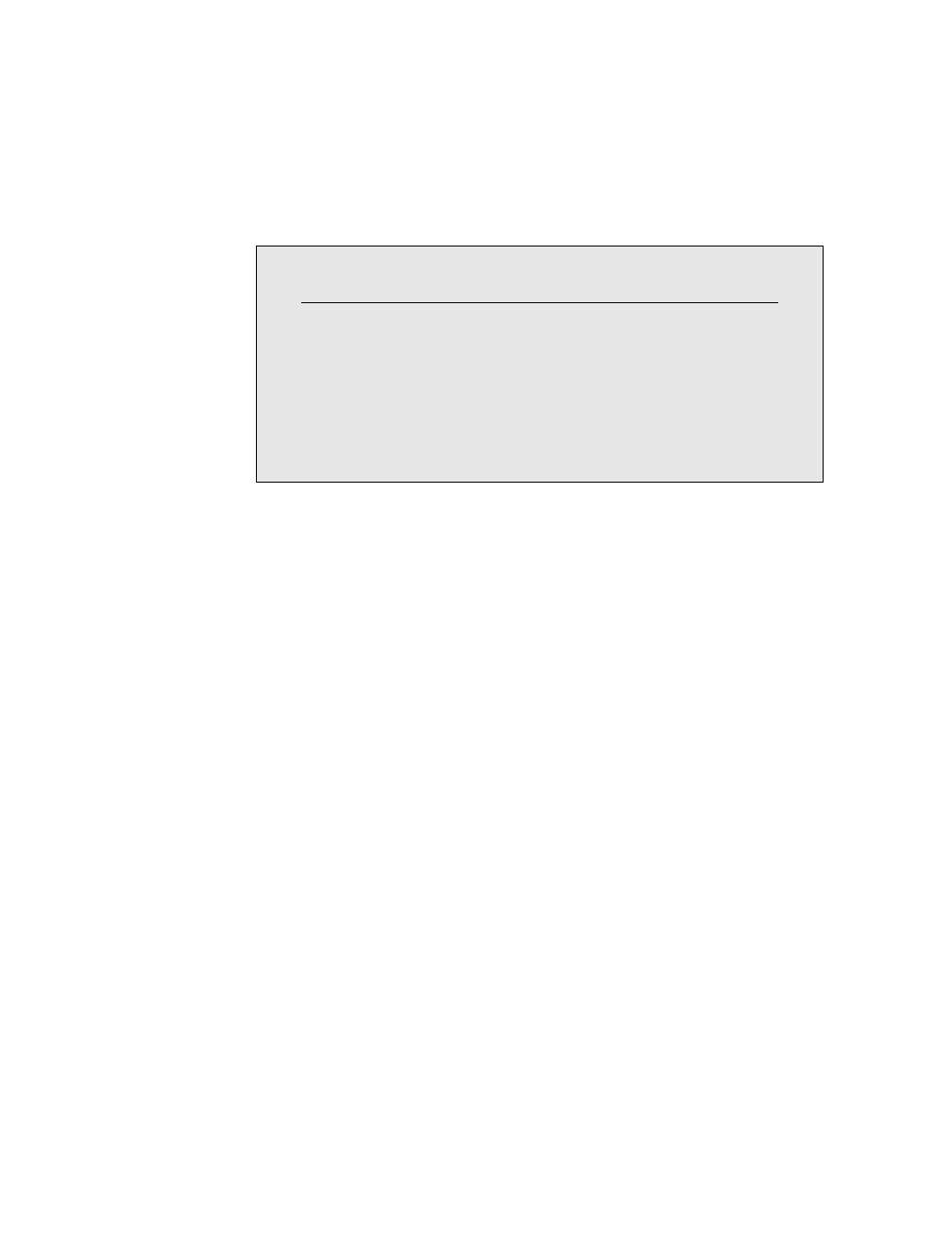

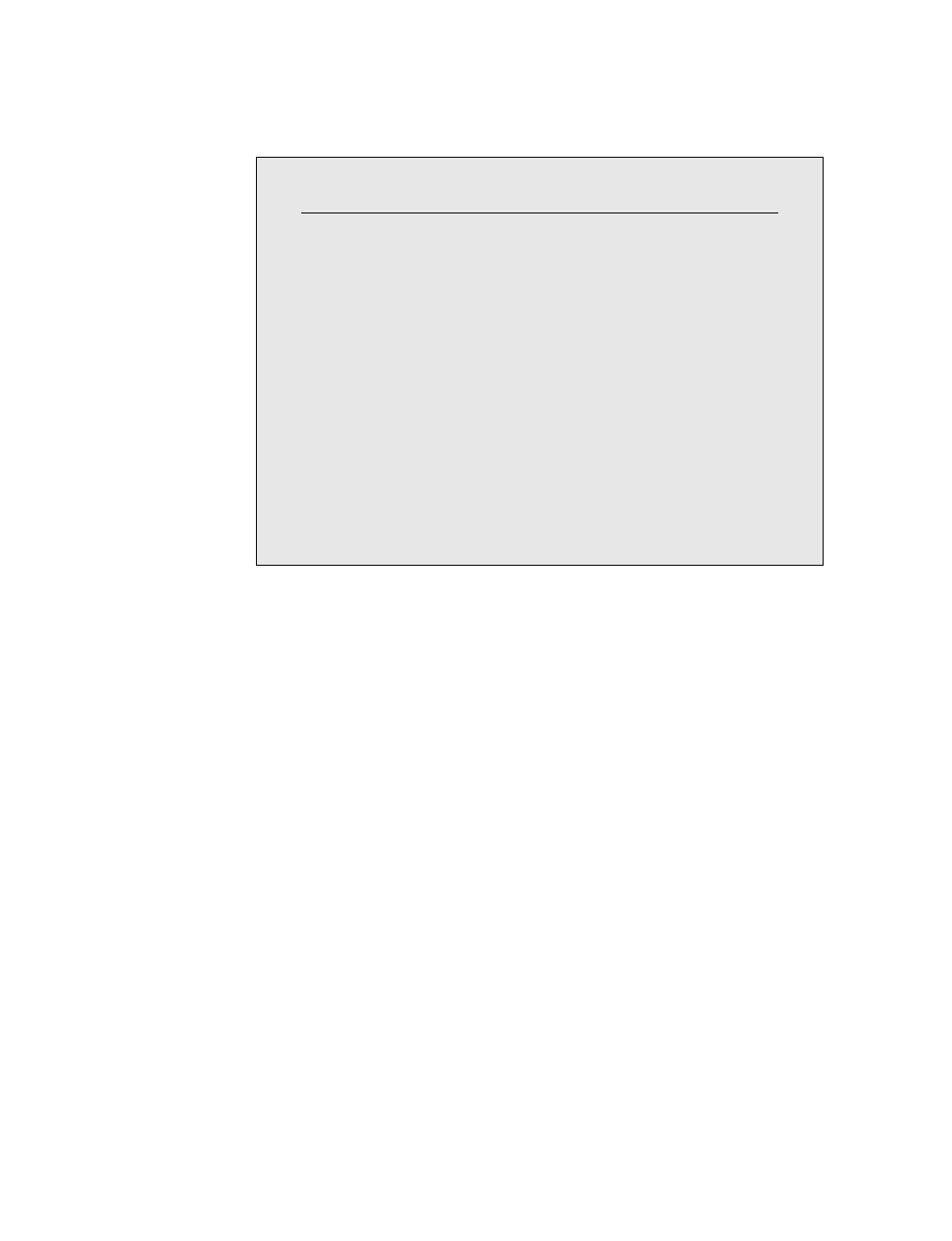

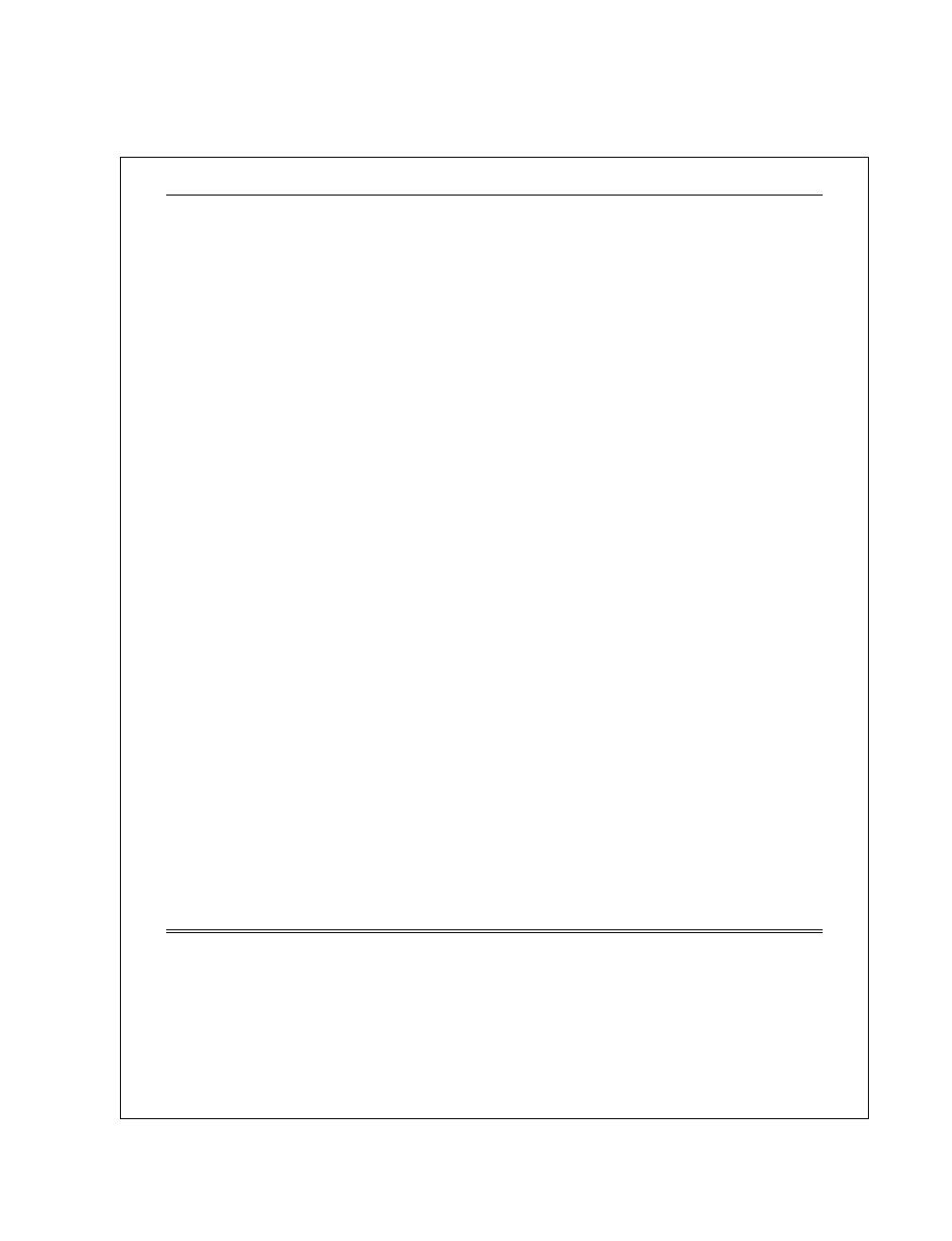

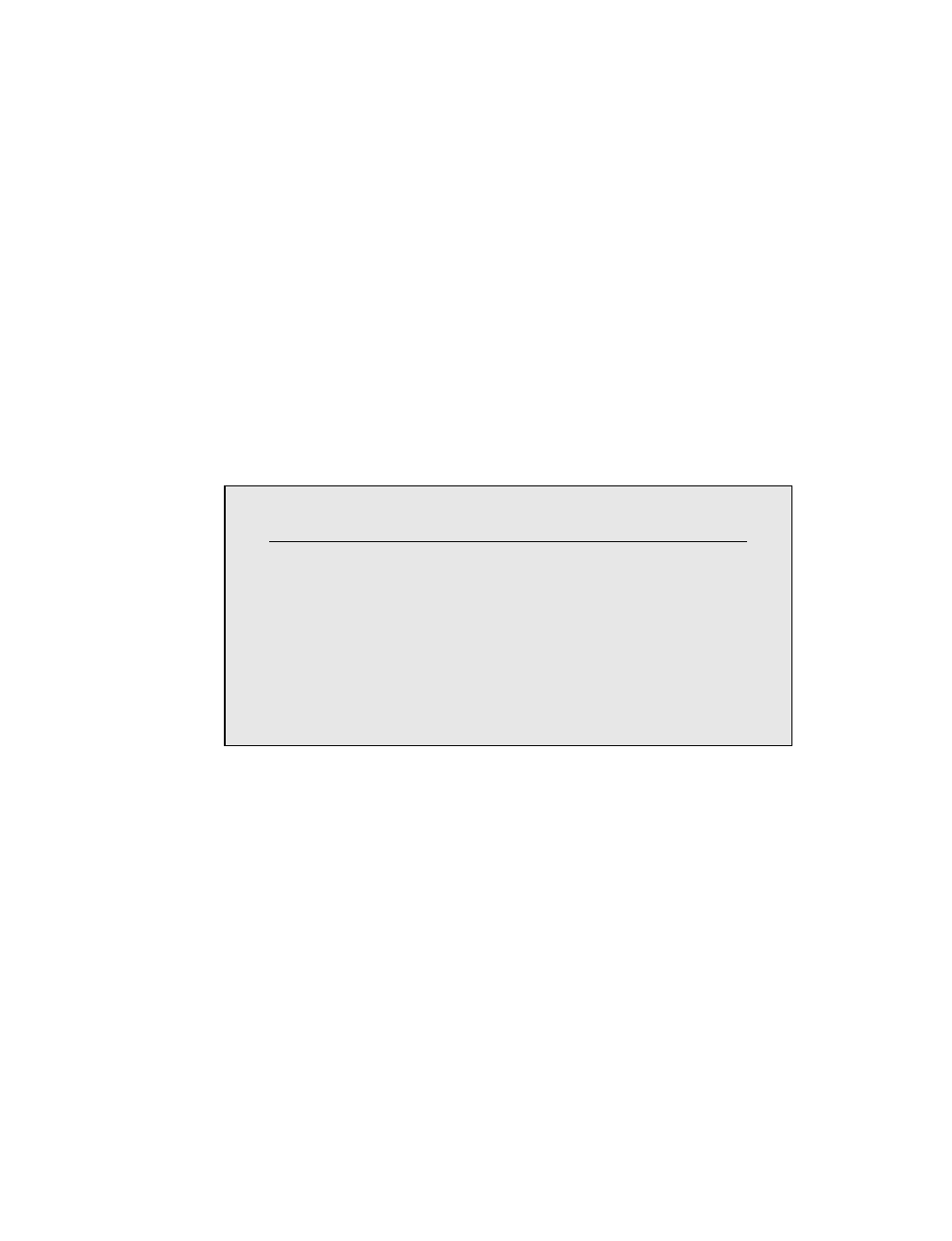

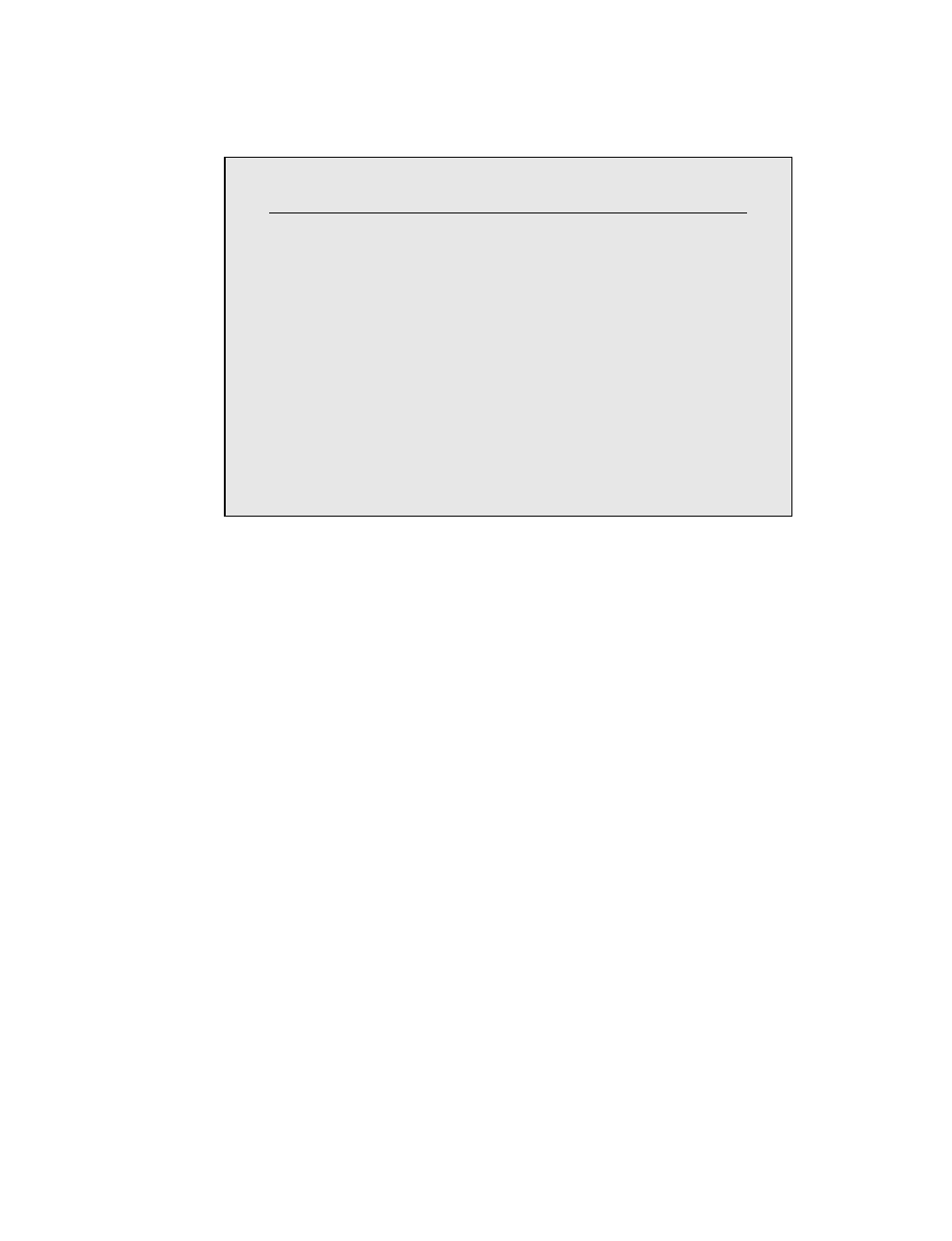

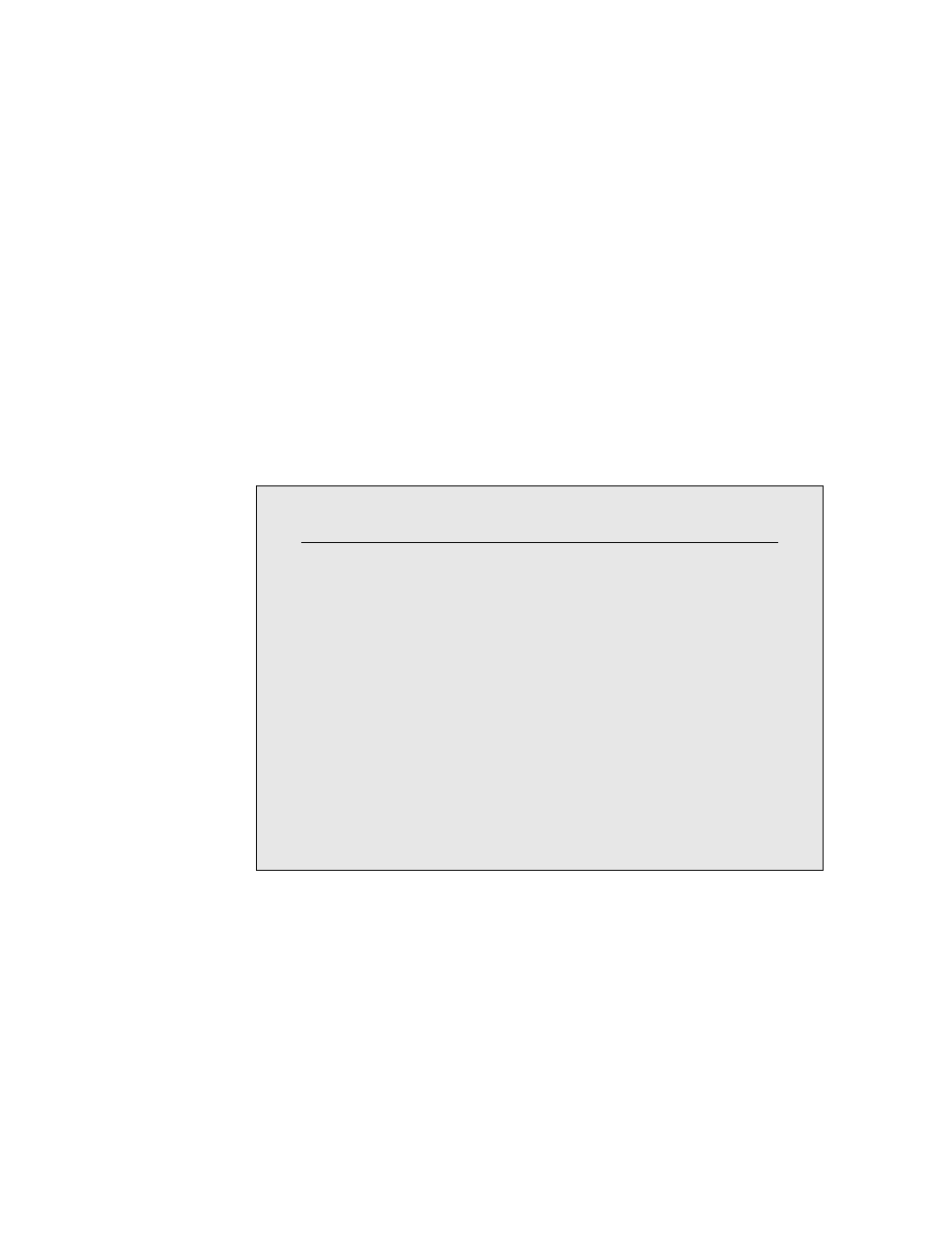

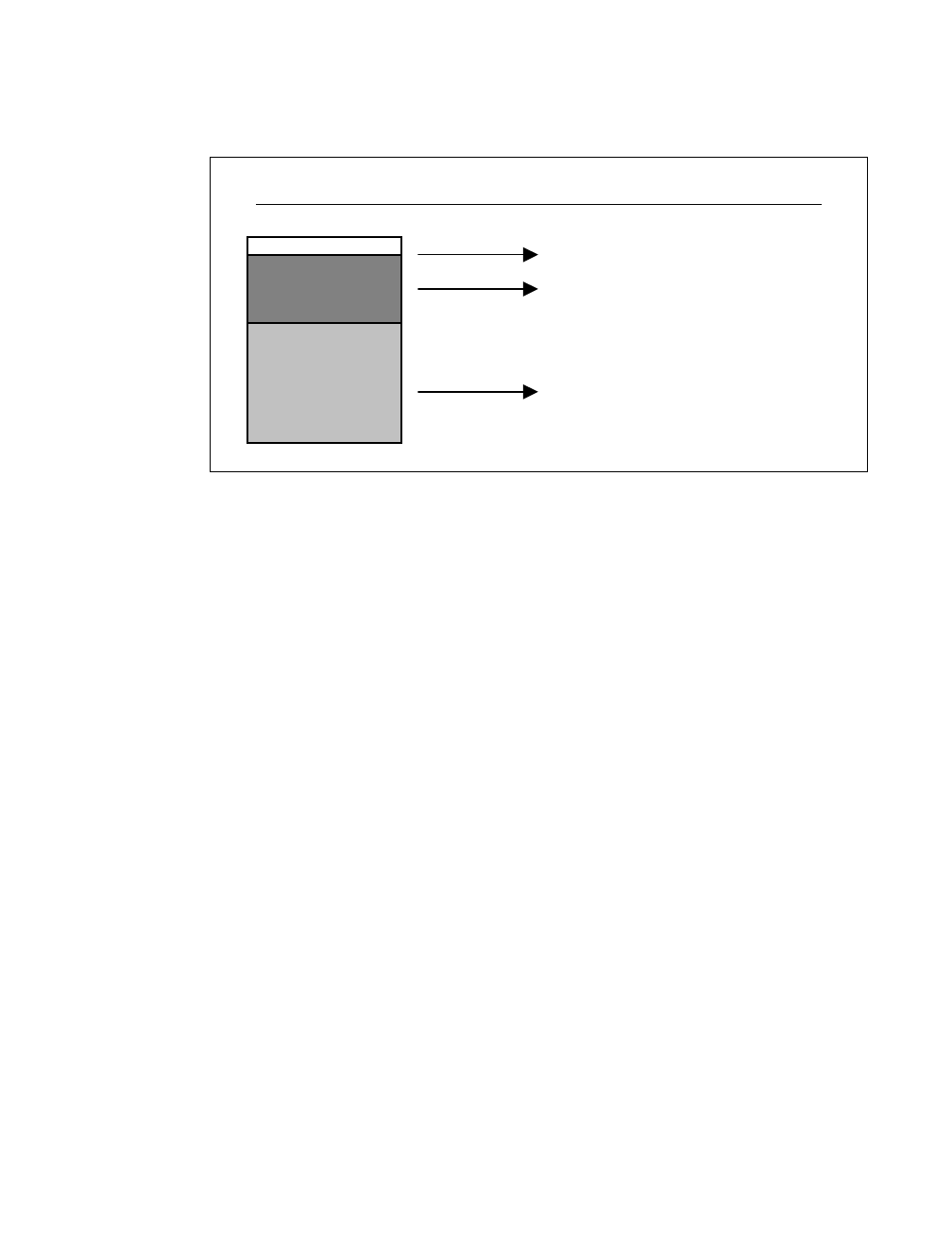

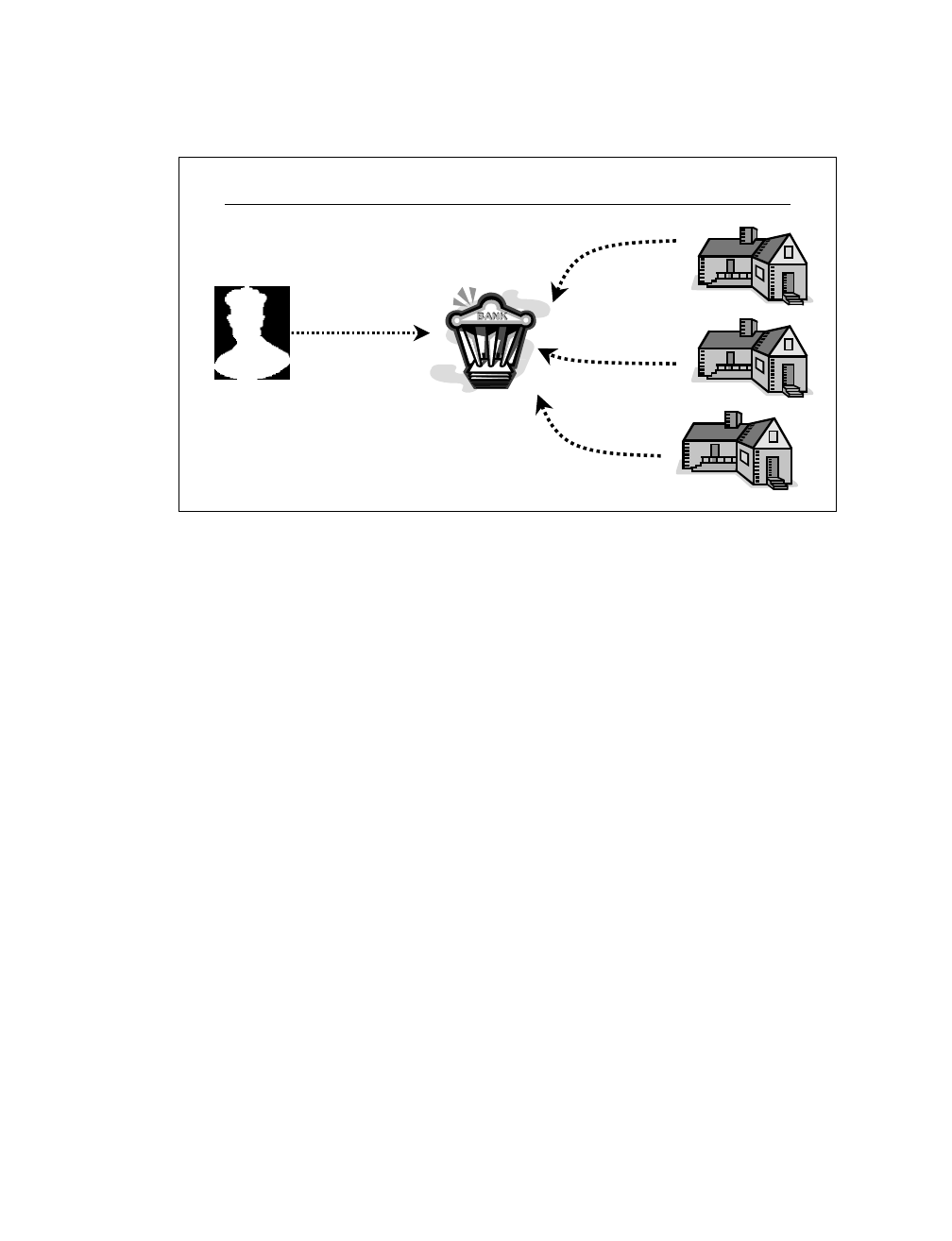

FIGURE 1.1

Owning Free and Clear versus Mortgaging

100%

Free and

Clear

90%

Financing

FREE AND CLEAR PROPERTY

Value = $100,000

Cash Investment = $100,000

Annual Net Income = $12,000

Return on Investment = 12%

90% FINANCED PROPERTY

Value = $100,000

Cash Investment = $10,000

Annual Net Income = $4,080

Return on Investment = 40.8%

10% Down

Payment

6

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Example:

Consider a $100,000 property that brings in

$10,000 per year in net income

(

net

means gross rents col-

lected, less expenses, such as property taxes, maintenance,

utilities, and hazard insurance

)

. The $100,000 in equity thus

yields a 10 percent annual return on investment

(

$10,000,

the annual net cash flow, divided by $100,000, the equity

investment

)

.

If the property were financed for 80 percent of its value

(

$80,000

)

at 7.5 percent interest, the monthly payment would be approximately

$560 per month, or $6,720 per year. Net rent of $10,000 per year

minus $6,720 in debt payments equals $3,280 per year in net cash

flow. Divide the $3,280 in annual cash flow by the $20,000 in equity

and you have a 16.4 percent return on investment. Furthermore, with

$80,000 more cash, you could buy four more properties. As you can

see, financing, even when you don’t necessarily “need” to do so, can

be more profitable than investing all of your cash in one property.

How Financing Affects the Real Estate Market

Because financing plays a large part in real estate sales, it also af-

fects values; the higher the interest rate, the larger your monthly pay-

ment. Conversely, the lower the interest rate, the lower the monthly

payment. Thus, the lower the interest rate, the larger the mortgage

loan you can afford to pay. Consequently, the larger the mortgage you

can afford, the more the seller can ask for in the sales prices.

Also, people with less cash are usually more concerned with

their payment than the total amount of the purchase price or loan

amount. On the other hand, people with all cash are more concerned

with price. Because most buyers borrow most of the purchase price,

the prices of houses are affected by financing. Thus, when interest

rates are low, housing prices tend to increase, because people can

afford a higher monthly payment. Conversely, when interest rates are

higher, people cannot afford as much a payment, generally driving

real estate prices down.

☛

1 / Introduction to Real Estate Financing

7

Since the mid-1990s, the prices of real estate have dramatically

increased in most parts of the country. The American economy has

grown, the job growth during this period has been good, but most

important, interest rates have been low.

How Financing Affects Particular Transactions

When valuing residential properties, real estate appraisers gener-

ally follow a series of standards set forth by professional associations

(

the most well-known is the Appraisal Institute

)

. Sales of comparable

properties are the general benchmark for value. Appraisers look not

just at housing sale prices of comparable houses, but also at the

financing associated with the sales of these houses. If the house was

owner-financed

(

discussed in Chapter 9

)

, the interest rate is generally

higher than conventional rates and/or the price is inflated. The price

is generally inf lated because the seller’s credit qualifications are

looser than that of a bank, which means the buyer will not generally

complain about the price.

Take a Cue from Other Industries

The explosion of the electronics market, the auto-

mobile market, and other large-ticket purchase

markets is directly affected by financing. Just

thumb through the Sunday newspapers and you

will see headlines such as “no money down” or

“no payments for one year.” These retailers have

learned that financing moves a product because it

makes it easier for people to justify the purchase.

Likewise, the price of a house may be stretched a

bit more when it translates to just a few dollars

more per month in mortgage payments.

8

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Appraisals on income properties are done in a variety of ways,

one of which is the “income” approach. The

income approach

looks

at the value of the property versus the rents the property can pro-

duce. While financing does not technically come into the equation, it

does affect the property’s profitability to the investor. Thus, a prop-

erty that can be financed at a lower interest rate will be more attrac-

tive to the investor if cash flow is a major concern.

How Real Estate Investors Use Financing

As discussed above, investors use mortgage loans to increase

their leverage. The more money an investor can borrow, the more he

or she can leverage the investment. Rarely do investors use all cash to

purchase properties, and when they do, it is on a short-term basis.

They usually refinance the property to get their cash back or sell the

property for cash.

Tax Impact of Financing

Down payments made on a property as an investor

are not tax-deductible. In fact, a large down pay-

ment offers no tax advantage at all because the in-

vestor’s tax basis is based on the purchase price,

not the amount he or she puts down. However, be-

cause mortgage interest is a deductible expense,

the investor does better tax wise by saving his or

her cash. Think about it: the higher the monthly

mortgage payment, the less cash f low, the less tax-

able income each year. While positive cash flow is

desirable, it does not necessarily mean that a prop-

erty is more profitable because it has more cash

flow. A larger down payment will obviously in-

crease monthly cash flow, but it is not always the

best use of your money.

1 / Introduction to Real Estate Financing

9

The challenge is that loans for investors are treated as high-risk

by lenders when compared to noninvestor

(

owner-occupied proper-

ties

)

loans. Lenders often look at leveraged investments as risky and

are less willing to loan money to investors. Lenders assume

(

often cor-

rectly

)

that the less of your own money you have invested, the more

likely you will be to walk away from a bad property. In addition, fewer

investor loan programs mean less competition in the industry, which

leads to higher loan costs for the investor. The goal of the investor thus

is to put forth as little cash as possible, pay the least amount in loan

costs and interest, while keeping personal risk at a minimum. This is

quite a challenge, and this book will reveal some of the secrets for

accomplishing this task.

When Is Cash Better Than Financing?

Using all cash to purchase a property may be better than financ-

ing in two particular situations. The first situation is a short-term deal,

that is, you intend to sell the house shortly after you buy it

(

known as

“flipping”

)

. When you have the cash to close quickly, you can gener-

ally get a tremendous discount on the price of a house. In this case,

financing may delay the transaction long enough to lose an opportu-

nity. Cash also allows you to purchase properties at a larger discount.

You’ve heard the expression, “money talks, BS walks.” This is particu-

larly true when making an offer to purchase a property through a real

estate agent. The real estate agent is more likely to recommend to his

or her client a purchase offer that is not contingent on the buyer

obtaining bank financing.

The second case is one in which you can use your retirement ac-

count. You can use the cash in your IRA or SEP to purchase real estate,

and the income from the property is tax-deferred. In order to do this,

you need an aggressive self-directed IRA custodian

(

oddly enough,

most IRA custodians view real estate as “risky” and the stock market as

“safe”

)

. Two such custodians are Mid Ohio Securities,

<

www.mi

doh.com

>

, or Entrust Administration,

<

www.entrustadmin.com

>

.

10

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

What to Expect from This Book

This book will show you how to finance properties with as little

cash as possible, while maintaining minimum risk and maximum

profit.

The first few chapters describe the mortgage loan process, legal

details, and the banking industry. Chapter 4 covers different types of

lenders and loans, and the benefits of each. Chapter 5 covers how to

creatively use institutional loan programs as an investor. Chapters 6,

7, 8, and 9 cover creative, noninstitutional financing.

As with any technique on real estate acquisition or finance, you

should review the process with a local professional, including an attor-

ney. Also, keep in mind that while most of these ideas are applicable

nationwide, local practices, laws, rules, customs, and market condi-

tions may require variations or adaptations for your particular use.

Key Points

•

Interest rates affect property values.

•

Financing affects the value of a property to an investor.

•

Investors use financing to leverage their investments.

Understanding a Cash Offer

versus Paying All Cash

If you make a “cash offer” on a property, it does not

necessarily mean you are using all of your own

cash. It means the seller is receiving all cash, as op-

posed to the seller financing some part of the pur-

chase price

(

discussed more fully in Chapter 9

)

.

11

CHAPTER

2

A Legal Primer on

Real Estate Loans

If there were no bad people there would be no good lawyers.

—Charles Dickens

Before we discuss lenders, loans, and loan terms, it is essential

that you understand the legal fundamentals and paperwork involved

with mortgage loans. By analogy, you cannot make a living buying and

selling automobiles without a working knowledge of engines and car

titles. Likewise, you need to understand how the paperwork fits into

the real estate transaction. Without a working knowledge of the

paperwork, you are at the mercy of those who have the knowledge.

Furthermore, without the know-how your risk of a large mistake or

missed opportunity increases tremendously.

What Is a Mortgage?

Most of us think of going to a bank to get a mortgage. Actually,

you go to the bank to get a loan. Once you are approved for the loan,

you sign a promissory note to the lender, which is a legal promise to

12

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

pay. You also give the lender

(

not get

)

a mortgage as security for repay-

ment of the note. A

mortgage

(

also called a “deed of trust” in some

states

)

is a security agreement under which the borrower pledges his

or her property as collateral for payment. The mortgage document is

recorded in the county property records, creating a lien on the prop-

erty in favor of the lender. See Figure 2.1.

If the underlying obligation

(

the promissory note

)

is paid off, the

lender must release the collateral

(

the mortgage

)

. The release will

remove the mortgage lien from the property. If you search the public

records of a particular property, you will see many recorded mort-

gages that have been placed and released over the years.

Promissory Note in Detail

A note is an IOU or promise to pay; it is a legal obligation. A

promissory note

(

also known as a “note” or “mortgage note”

)

spells

out the amount of the loan, the interest to be paid, how and when pay-

ments are made, and what happens if the borrower defaults. The note

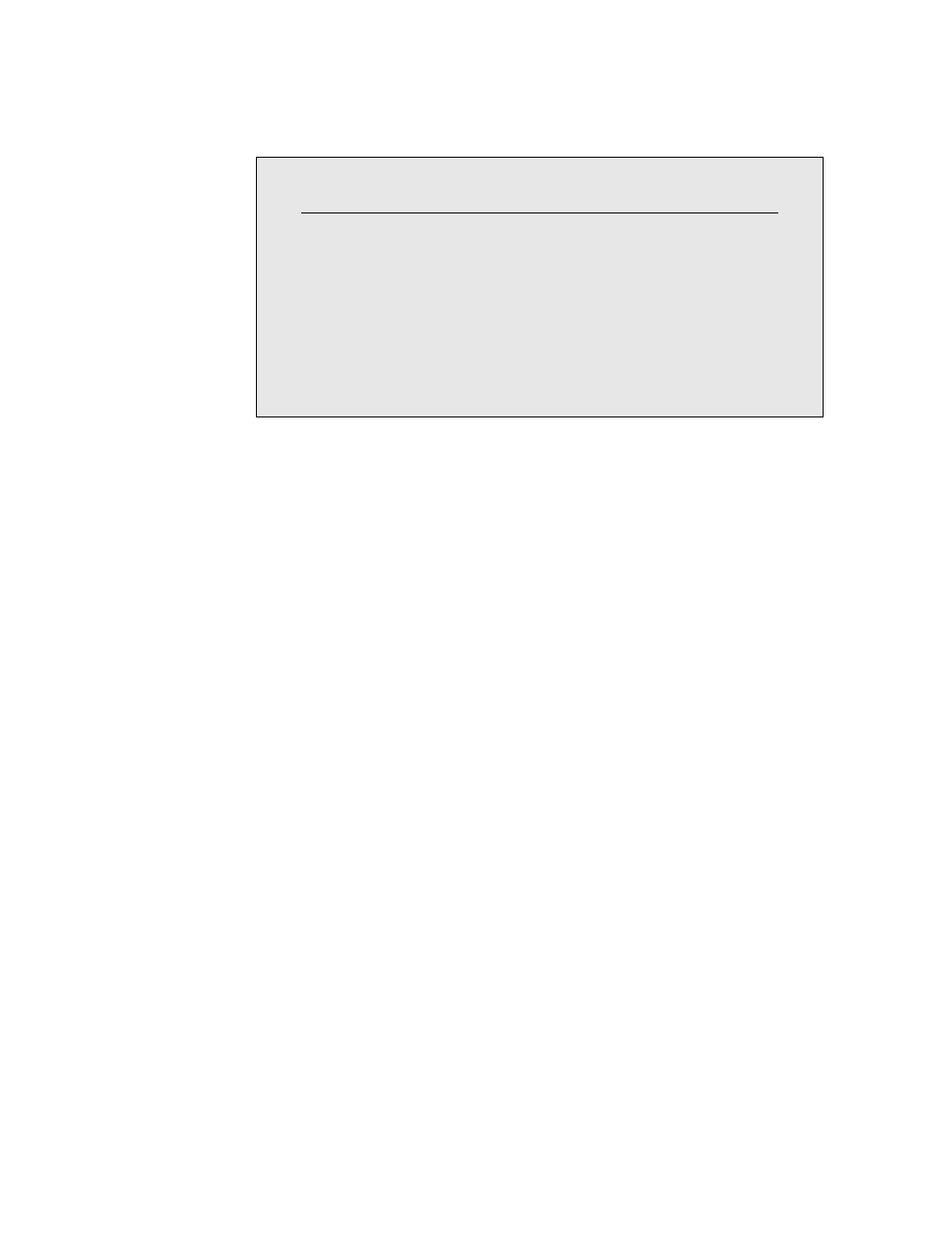

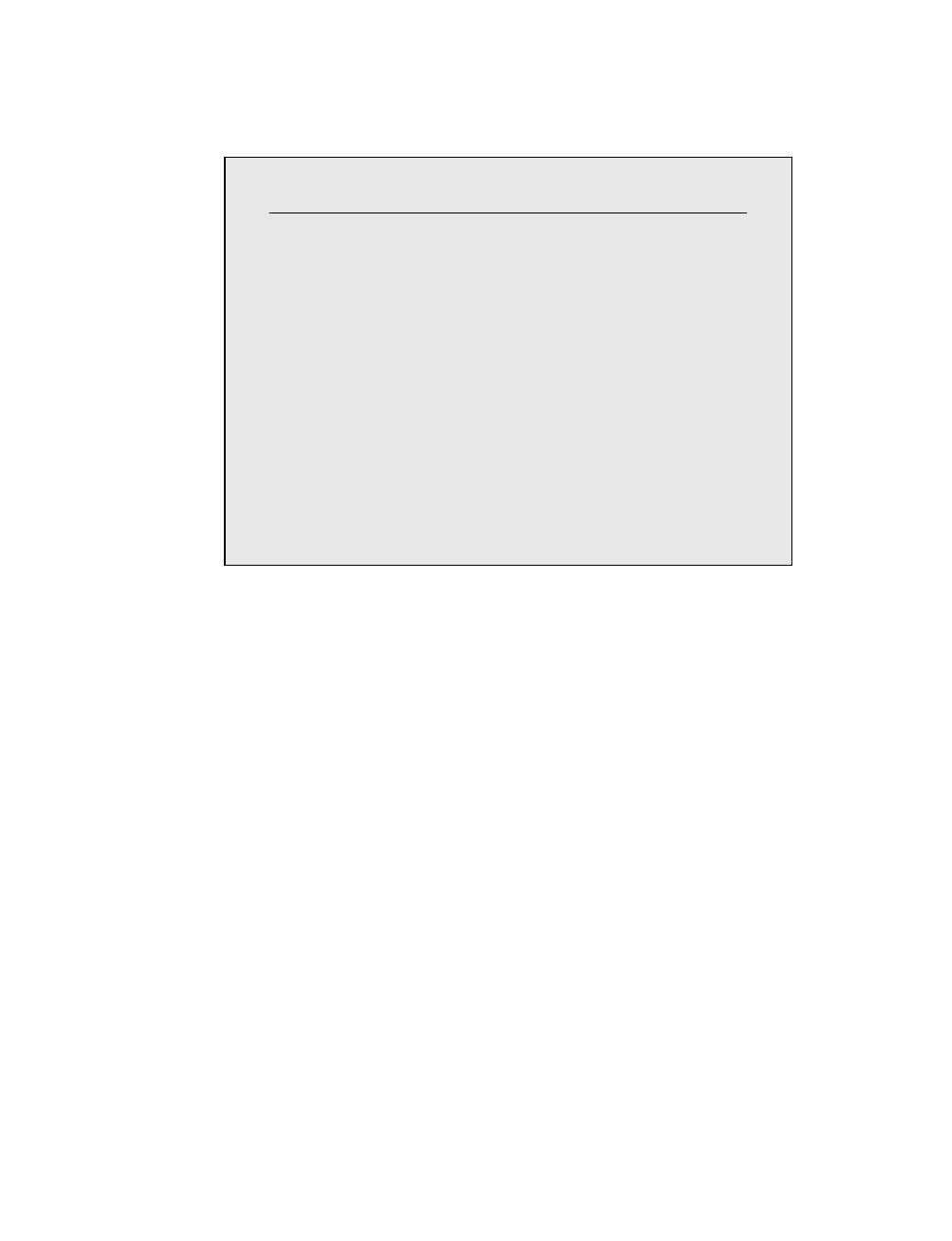

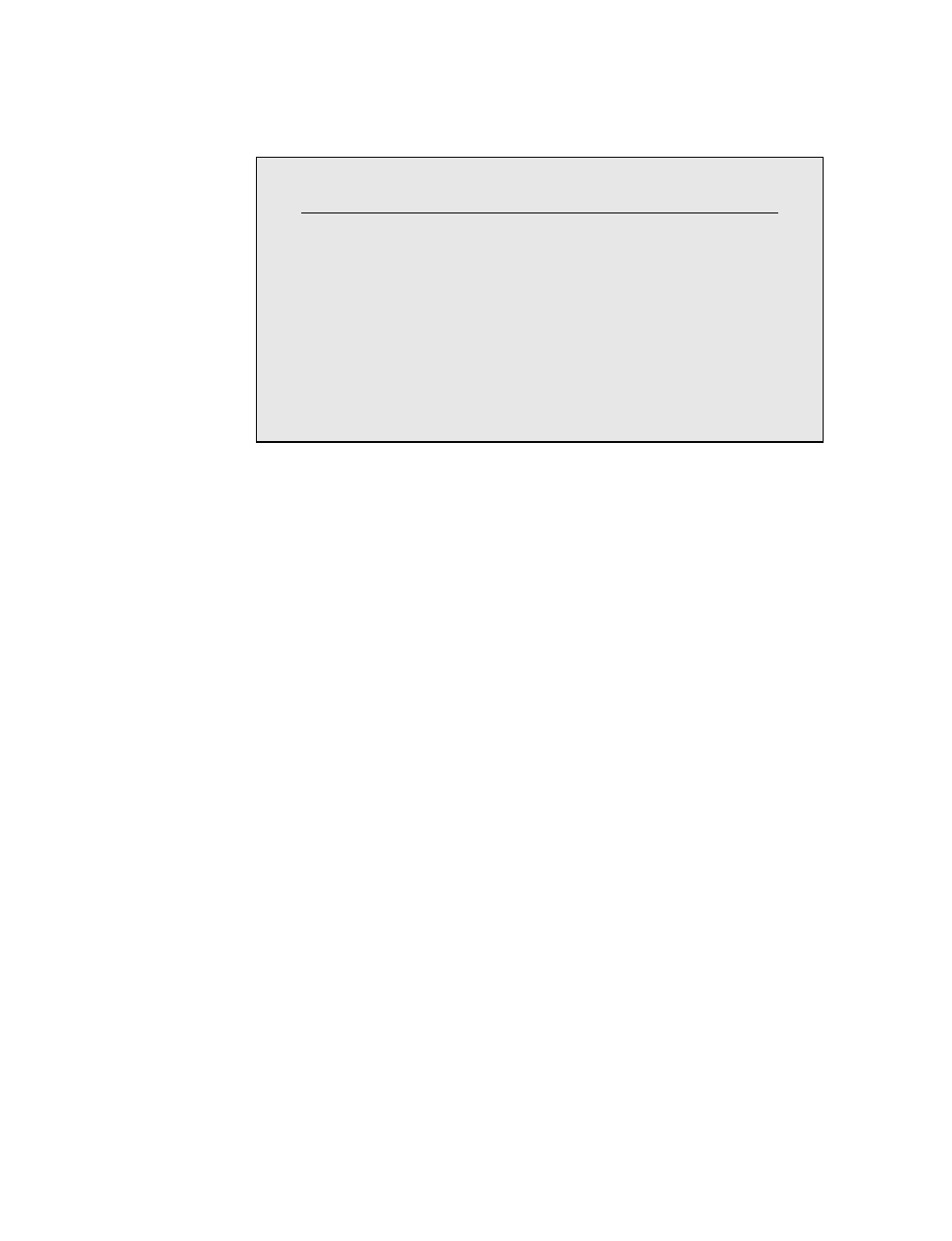

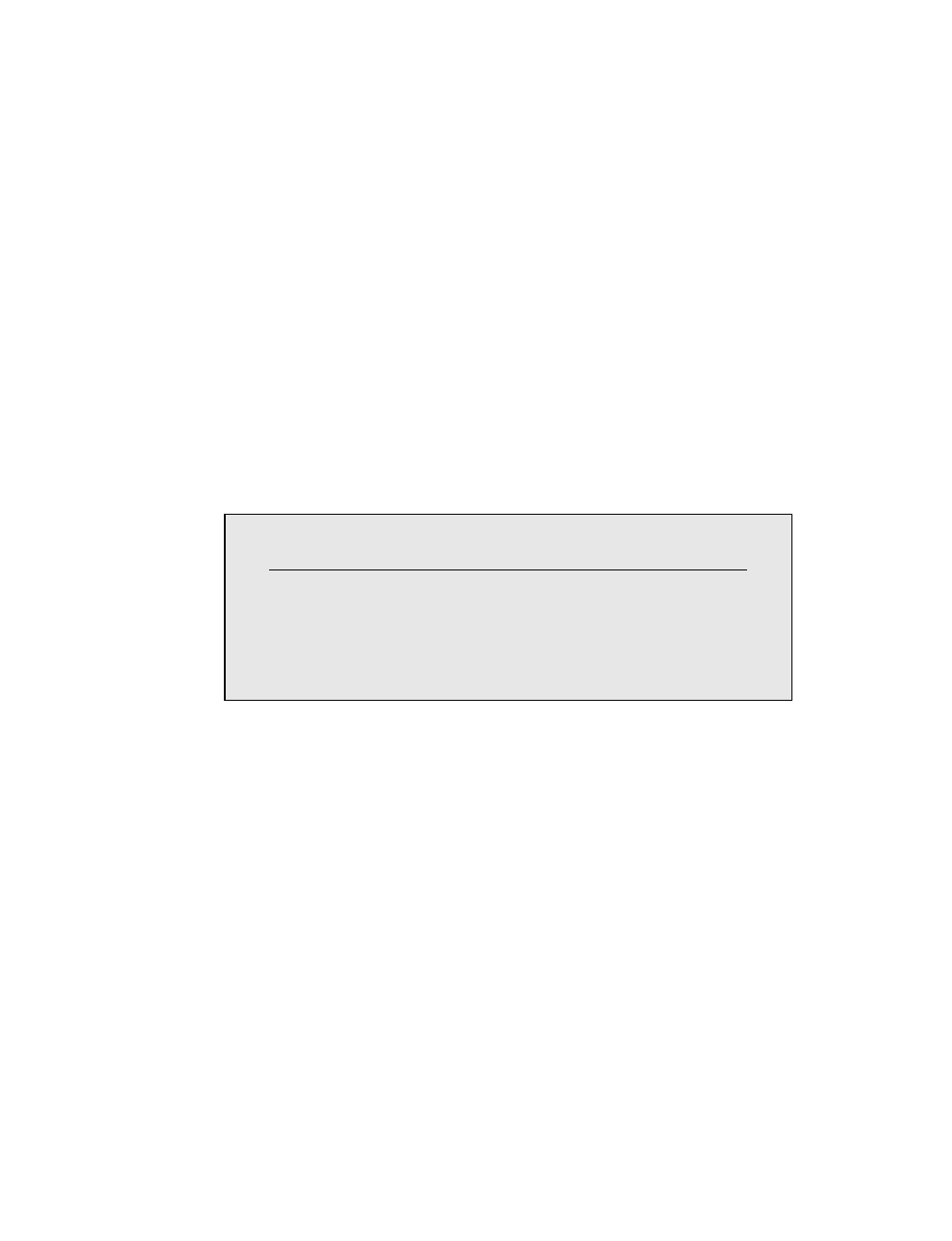

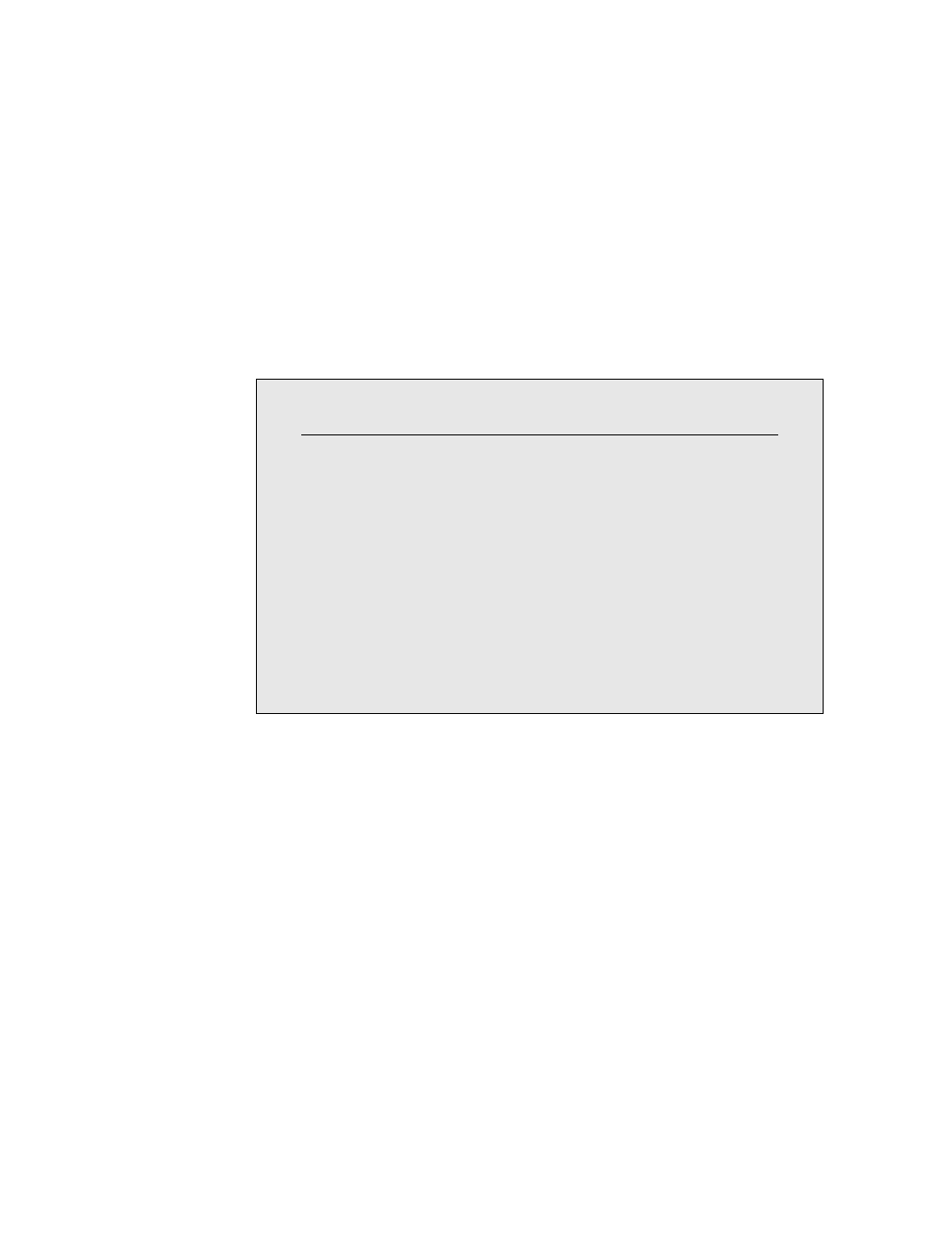

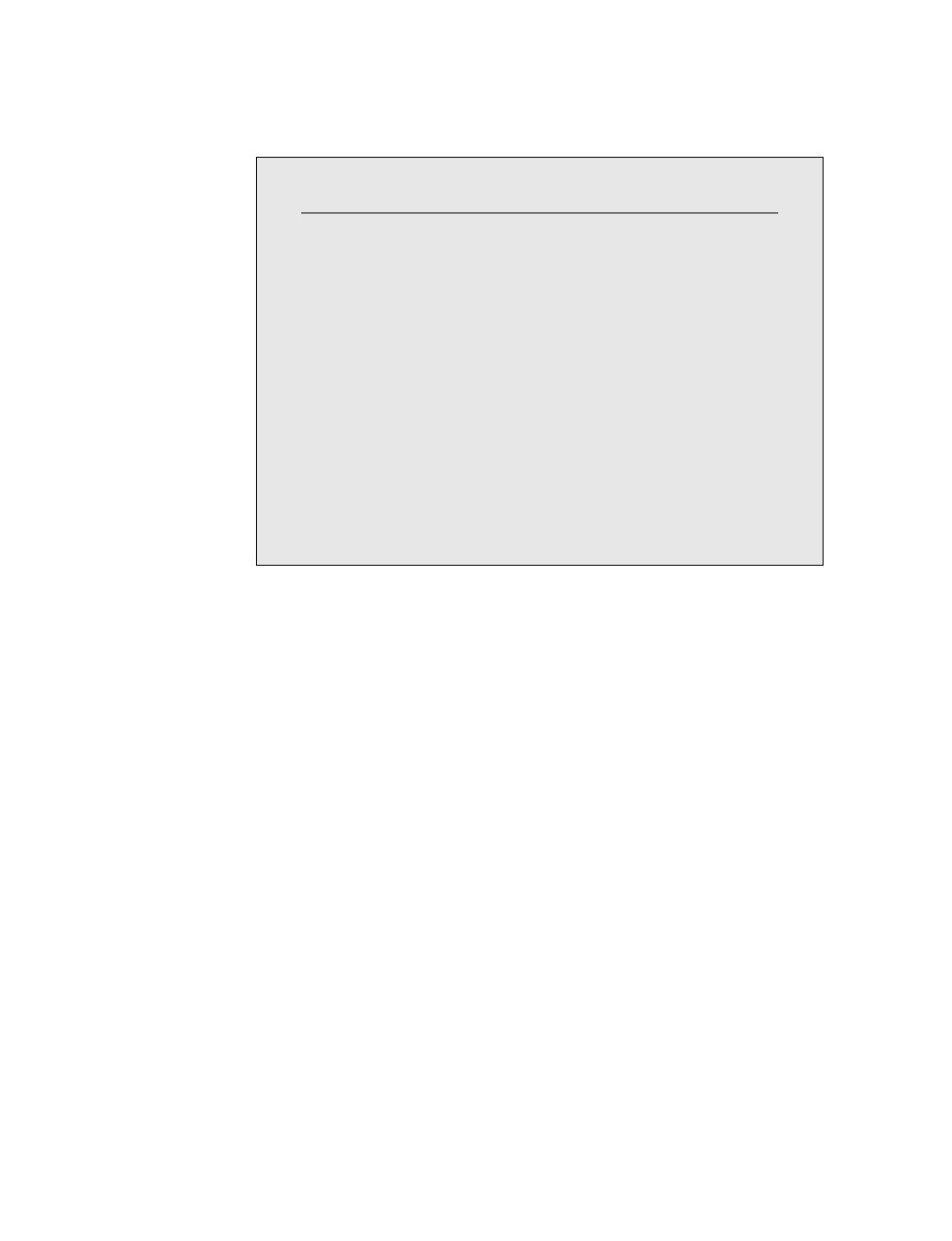

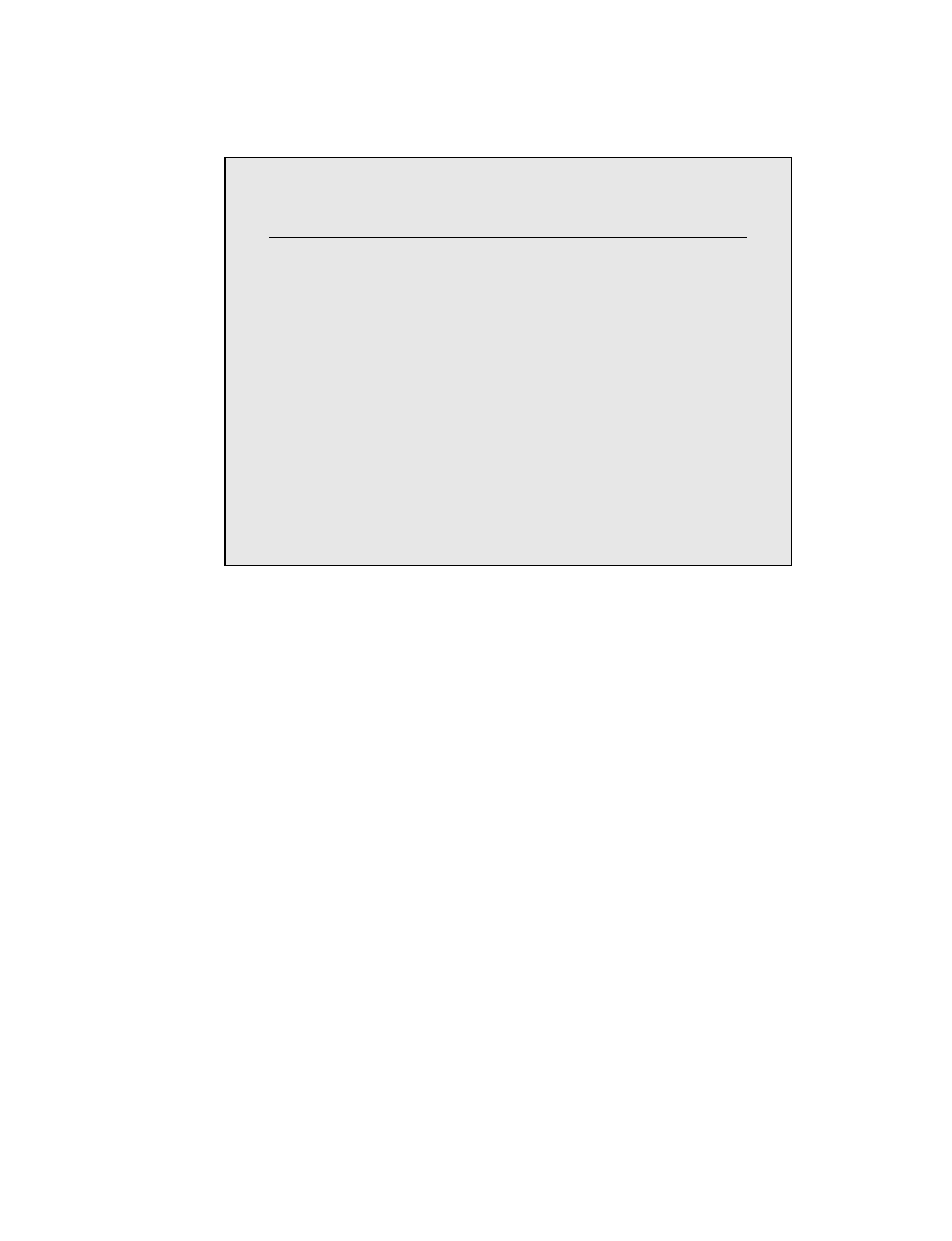

FIGURE 2.1

The Mortgage Transition

Promissory Note:

Legal Obligation to Pay

Security Instrument

(Mortgage or Deed of Trust)

Collateral for Note

Lender Borrowe

r

2 /A Legal Primer on Real Estate Loans

13

may also contain disclosures and other provisions required by federal

or state law.

Most lenders use a form of note that is approved by the Federal

National Mortgage Association

(

FNMA, or Fannie Mae

)

. A sample

form of this note can be found in Appendix C. The note is signed

(

in

legal terms, “executed”

)

by the borrower. The original note is held by

the lender until the debt is paid in full, at which time the original note

is returned to the borrower marked “paid in full.”

A Mortgage Note Is a Negotiable Instrument

Like a check, a mortgage note can be assigned and

collected by whoever holds the note. As discussed

in Chapter 3, mortgage notes are often bought,

sold, traded, and hypothecated

(

pledged as col-

lateral

)

.

A Promissory Note Is a Personal Obligation

Because promissory notes are personal obliga-

tions, the history of payments will appear on your

credit file, even if the debt is used for investment.

If you fail to pay on the note, your credit will be

adversely affected, and you risk a lawsuit from the

lender. Some notes are nonrecourse, that is, the

lender cannot sue you personally. Although not

always possible, you should try to make sure most

of your debt is nonrecourse.

14

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

The Mortgage in Detail

The security agreement executed by the borrower pledges the

property as collateral for the note. Known by most as a “mortgage,”

this document, when recorded

(

discussed below

)

, creates a lien in

favor of the lender. The mortgage agreement is generally a standard-

ized form approved by FNMA. While the form of note is generally the

same from state to state, the mortgage form differs slightly because

the legal process of foreclosure

(

the lender’s right to proceed against

the collateral

)

is different in each state. See Figure 2.2.

The mortgage document will state that upon default of the note,

the lender can exercise its right to foreclose on the property. Foreclo-

sure is the process of lenders exercising their legal right to proceed

against the collateral for the loan

(

discussed later in this chapter

)

. It

also places other obligations upon the borrower, such as

•

maintaining the property,

•

paying property taxes, and

•

keeping the property insured.

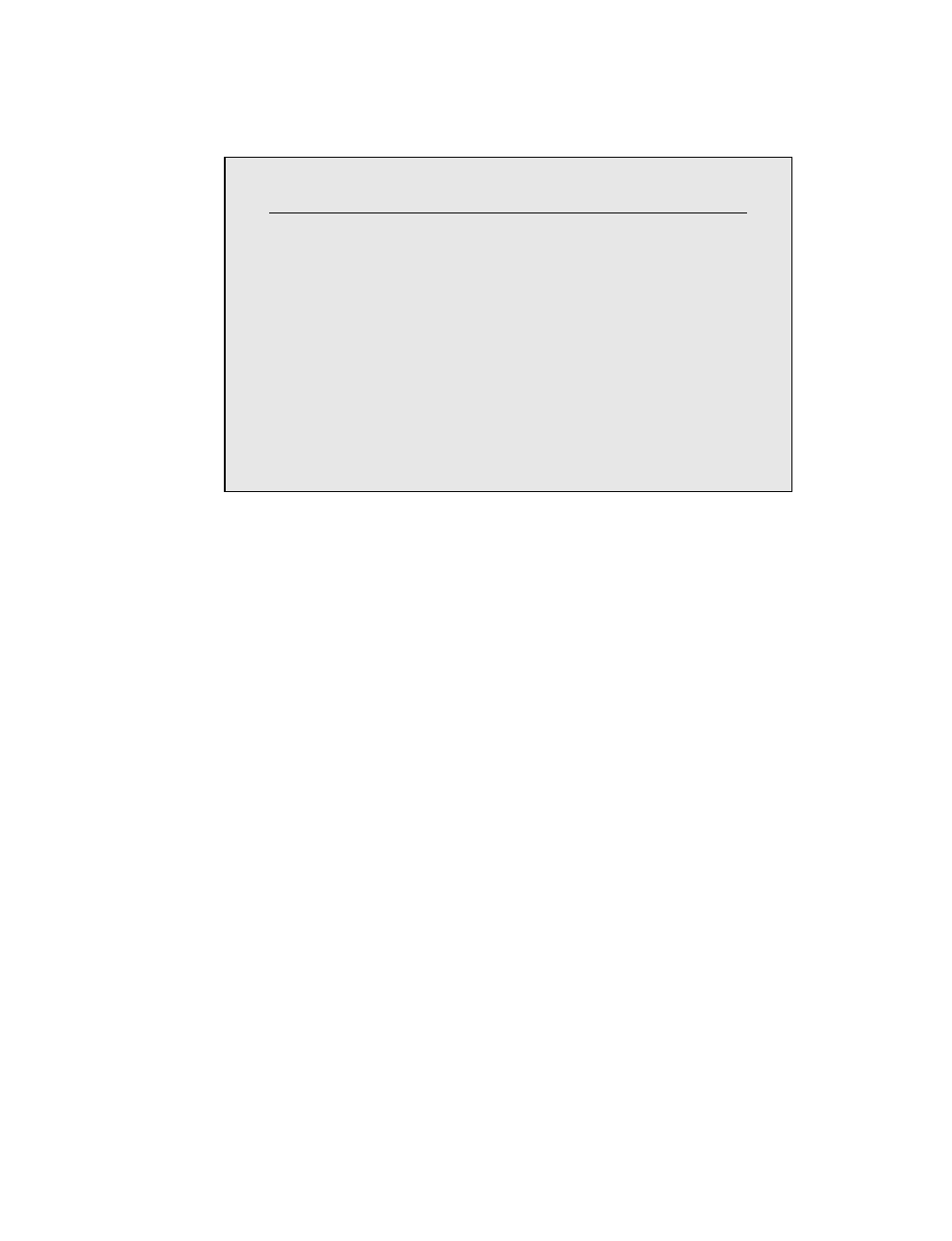

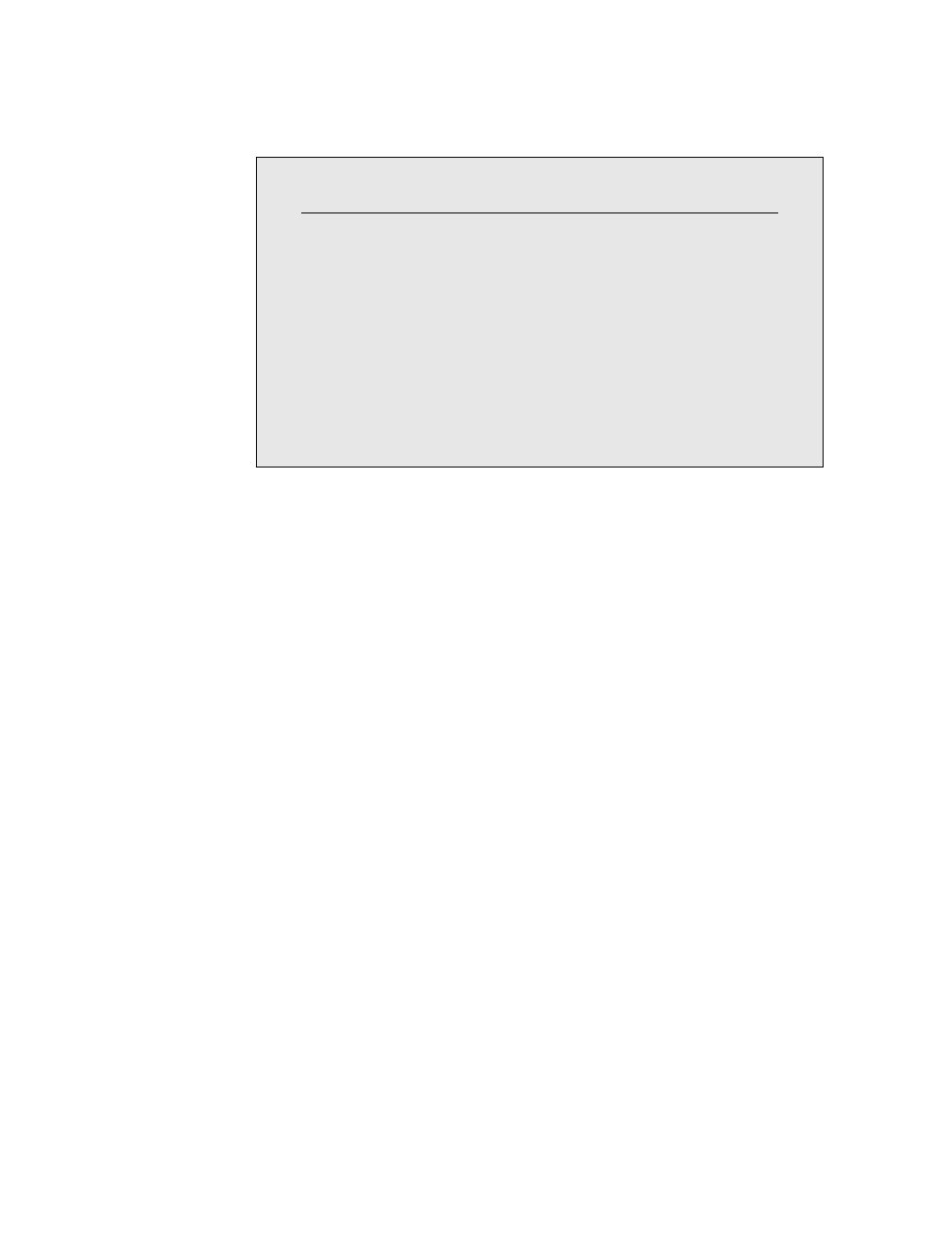

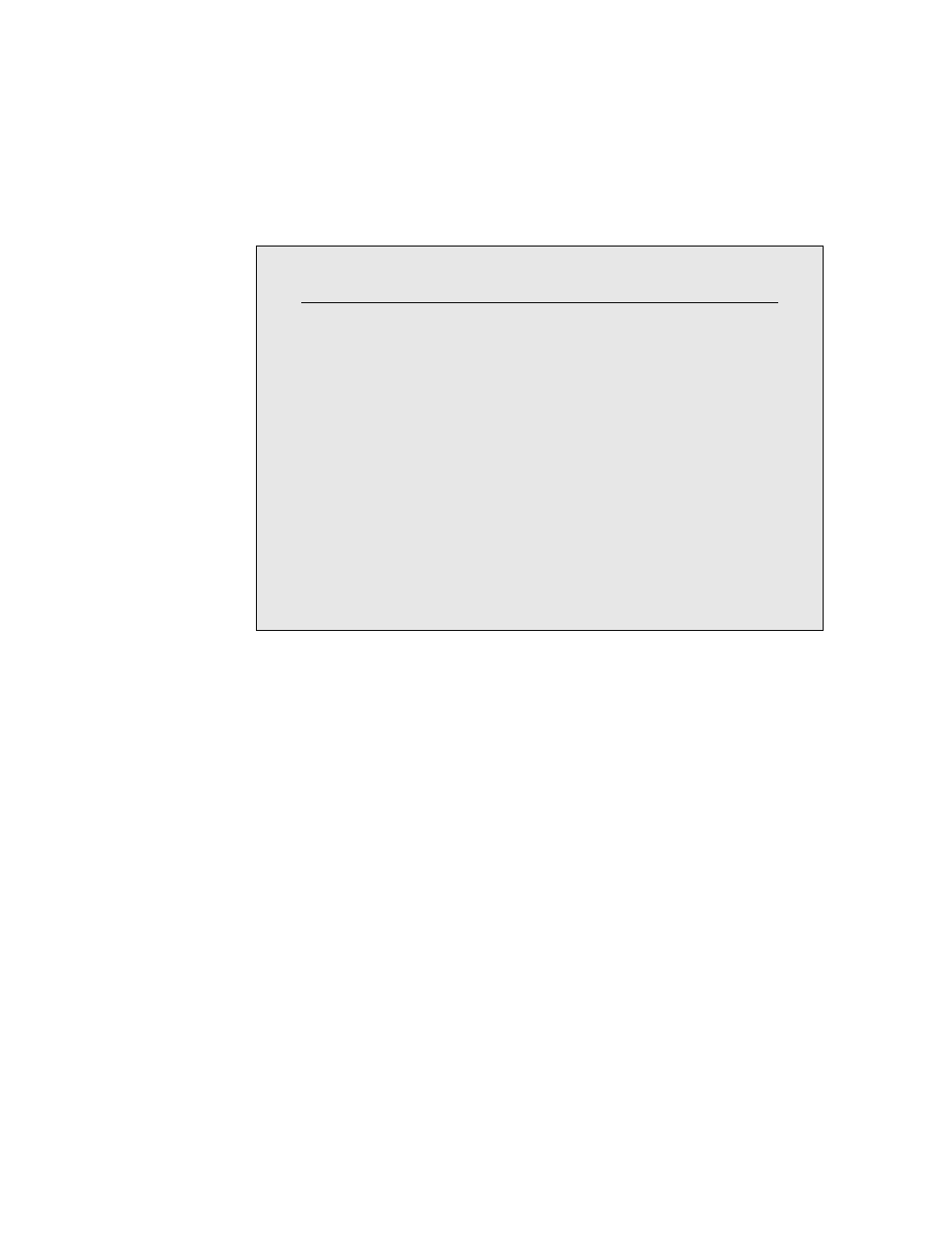

FIGURE 2.2

Parties to a Mortgage

Borrower/

Mortgagor

Lender/

Mortgagee

2 /A Legal Primer on Real Estate Loans

15

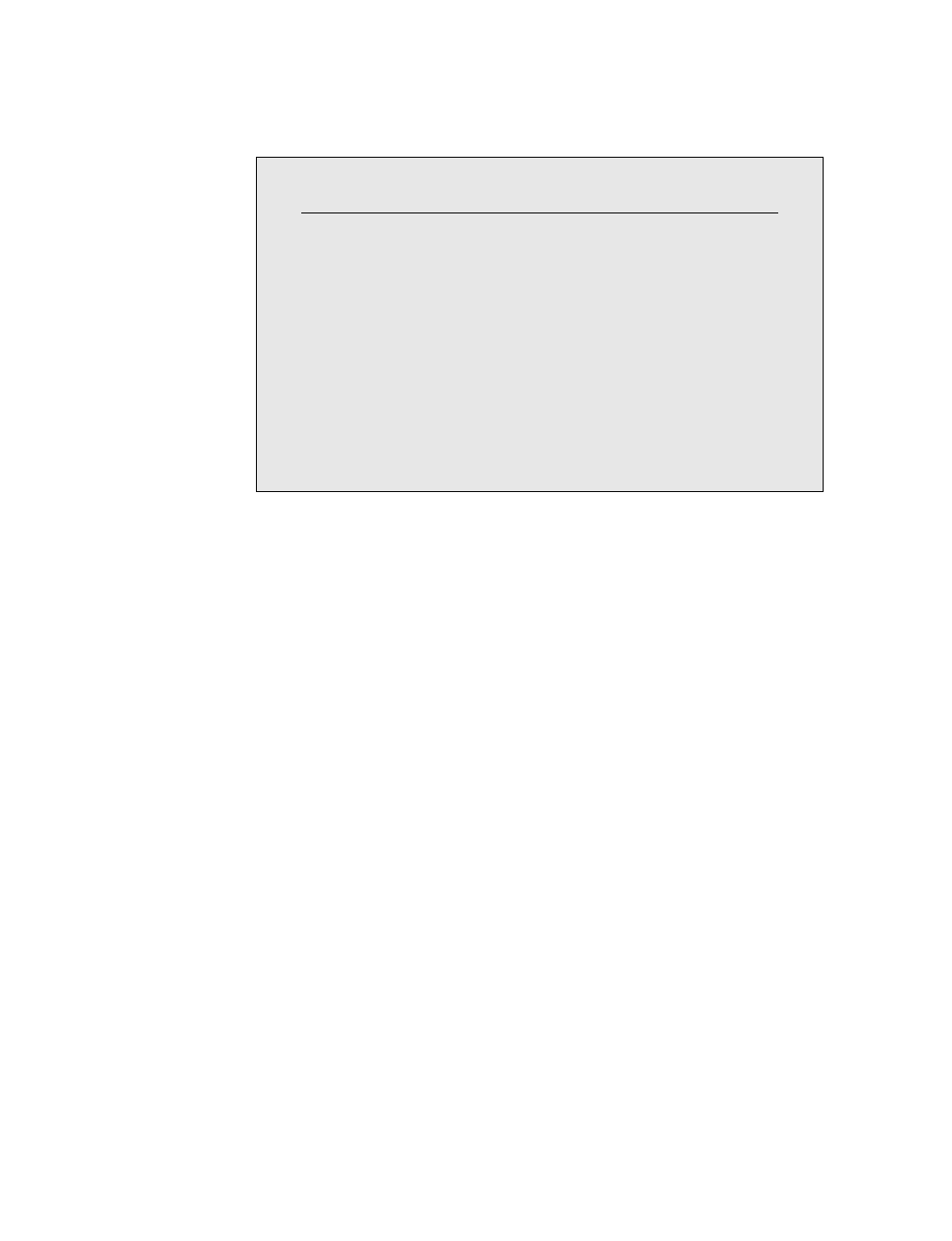

The Deed of Trust

Some states

(

e.g., California

)

use a document called a “deed of

trust”

(

AKA “trust deed”

)

rather than a mortgage. The

deed of trust

is

a document in which the trustor

(

borrower

)

gives a deed to the neutral

third party

(

trustee

)

to hold for the beneficiary

(

lender

)

. A deed of

trust is worded almost exactly the same as a mortgage, except for the

names of the parties. Thus, the deed of trust and mortgage are essen-

tially the same, other than the foreclosure process. See Figure 2.3.

The Public Recording System

The recording system gives constructive notice to the public of

the transfer of an interest in property. Recording simply involves

bringing the original document to the local county courthouse or

county clerk’s office. The original document is copied onto a com-

puter file or onto microfiche and is returned to the new owner. There

is a filing fee of about $6 to $10 per page for recording the document.

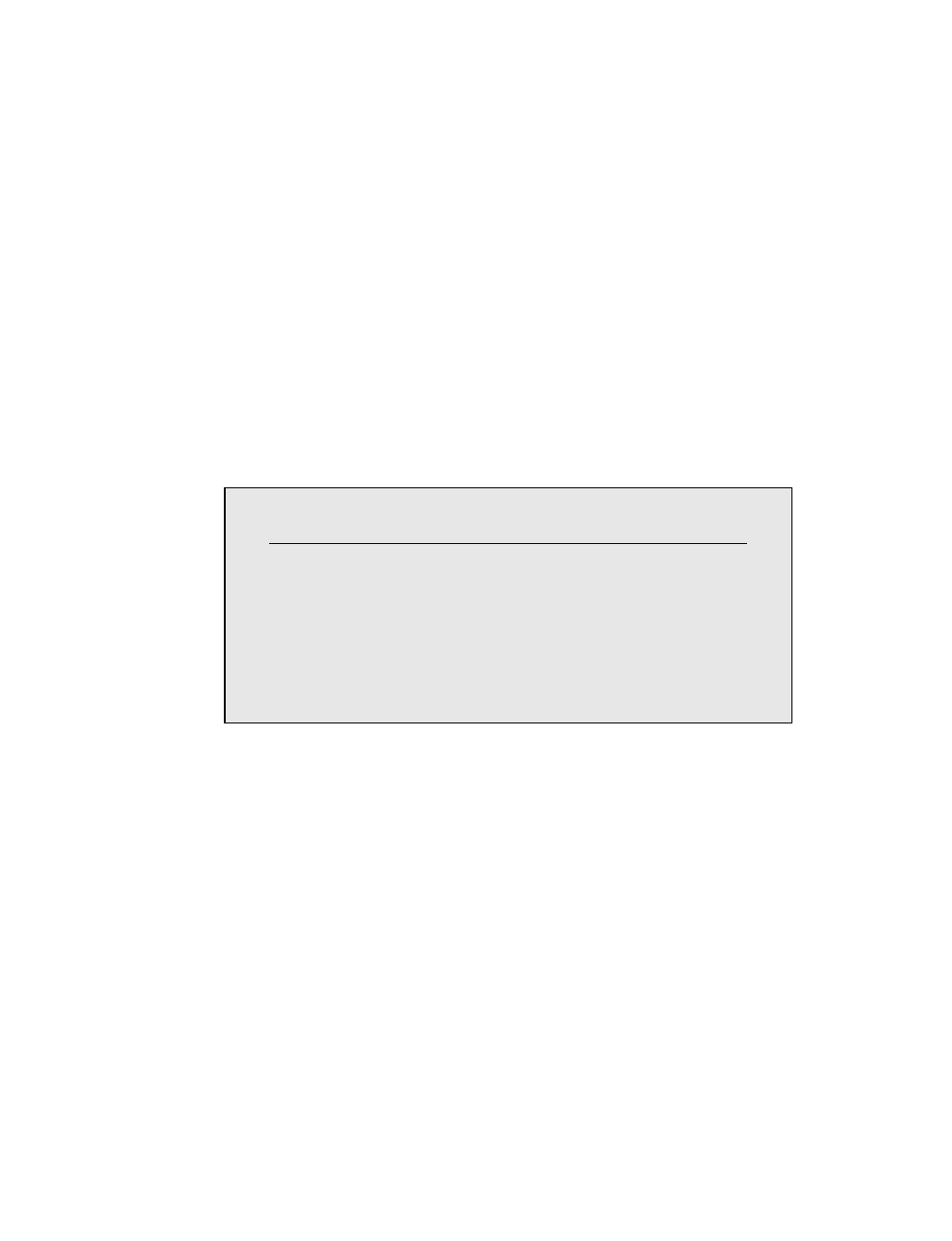

FIGURE 2.3

Parties to a Deed of Trust

Borrower/

Trustor

Lender/

Beneficiary

Trustee

16

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

In addition, the county, city, and/or state may assess a transfer tax

based on either the value of the property or the mortgage amount.

A deed or other conveyance does not have to be recorded to be

a valid transfer of an interest. For example, what happens if John gives

title to Mary, then he gives it again to Fred, and Fred records first?

What happens if John gives a mortgage to ABC Savings and Loan, but

the mortgage is not filed for six months, and then John immediately

borrows from another lender who records its mortgage first? Who

wins and loses in these scenarios?

Most states follow a “race-notice” rule, meaning that the first per-

son to record his document, wins, so long as

•

he received title in good faith,

•

he paid value, and

•

he had no notice of a prior transfer.

Example:

John buys a home and, in so doing, borrows

$75,000 from ABC Savings Bank. John signs a promissory

note and a mortgage pledging his home as collateral. Because

ABC messes up the paperwork, the mortgage does not get re-

corded for 18 months. In the interim, John borrows $12,000

from The Money Store, for which he gives a mortgage as col-

lateral. The Money Store records its mortgage, unaware of

John’s unrecorded first mortgage to ABC. The Money Store

will now have a first mortgage on the property.

Priority of Liens

Liens, like deeds, are “first in time, first in line.” Thus, if a prop-

erty is owned free and clear, a mortgage recorded will be a

first mort-

gage.

A mortgage recorded thereafter will be a

second mortgage

(

sometimes called a

junior mortgage

because its lien position is be-

hind the first mortgage

)

. Likewise, any judgments or other liens re-

corded later are also junior liens. Holding a first mortgage is a desirable

☛

2 /A Legal Primer on Real Estate Loans

17

position because a foreclosure on a mortgage can wipe out all liens

that are recorded behind it

(

called “junior lien holders”

)

. The process

of foreclosure will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

At the closing of a typical real estate sale, the seller conveys a

deed to the buyer. Most buyers obtain a loan from a conventional

lender for most of the cash needed for the purchase price. As dis-

cussed earlier, the lender gives the buyer cash to pay the seller, and

the buyer gives the lender a promissory note. The buyer also gives the

lender a security instrument

(

mortgage or deed of trust

)

under which

she pledges the property as collateral. When the transaction is com-

plete, the buyer has the title recorded in her name and the lender has

a lien recorded on the property.

What Is Foreclosure?

Foreclosure

is the legal process of the mortgage holder taking

the collateral for a promissory note in default. The process is slightly

different from state to state, but there are basically two types of fore-

closure: judicial and nonjudicial. In mortgage states, judicial foreclo-

sure is used most often, whereas in deed of trust states, nonjudicial

(

called power of sale

)

foreclosure is used. Most states permit both

types of proceedings, but it is common practice in most states to

exclusively use one method or the other. A complete state-by-state list

of foreclosure proceedings can be found in Appendix B.

Judicial Foreclosure

Judicial foreclosure is a lawsuit that the lender

(

mortgagee

)

brings against the borrower

(

mortgagor

)

to force the sale of the prop-

erty. About one-third of the states use judicial foreclosure. Like all law-

suits, a judicial foreclosure starts with a summons

(

a legal notice of

the lawsuit

)

served on the borrower and any other parties with infe-

rior rights in the property.

(

Remember, all junior liens, including ten-

18

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

ancies, are wiped out by the foreclosure, so they all need to be given

legal notice of the proceeding.

)

If the borrower does not file an answer to the lawsuit, the lender

gets a judgment by default. A person is then appointed by the court to

compute the total amount due including interest and attorney’s fees.

The lender then must advertise a notice of sale in the newspaper for

several weeks.

If the total amount due is not paid by the sale date, a public sale

is held on the courthouse steps. The entire process can take as little

as a few months to a year depending on your state and the volume of

court cases in your county.

The sale is conducted like an auction, in that the property goes

to the highest bidder. Unless there is significant equity in the prop-

erty, the only bidder at the sale will be a representative of the lender.

The lender can bid up to the amount it is owed, without having to

actually come out of pocket with cash to purchase the property. Once

the lender has ownership of the property, it will try to sell it through

a real estate agent.

If the proceeds from the sale are insufficient to satisfy the amount

owed to the lender, the lender may be entitled to a deficiency judg-

ment against the borrower and anyone else who guaranteed the loan.

Some states prohibit a lender from obtaining a deficiency judgment

against a borrower

(

applies only to owner-occupied, not investor prop-

erties

)

. In practice, few lenders seek a deficiency judgment against the

borrower.

Nonjudicial Foreclosure

A majority of the states permit a lender to foreclose without a law-

suit, using what is commonly called a “power of sale.” Upon default of

the borrower, the lender simply files a notice of default and a notice of

sale that is published in the newspaper. The entire process generally

takes about 90 days.

2 /A Legal Primer on Real Estate Loans

19

Strict Foreclosure

Two states—New Hampshire and Connecticut—permit strict

foreclosure, which does not require a sale. When the court proceed-

ing is started, the borrower has a certain amount of time to pay what

is owed. Once that date has passed, title reverts to the lender without

the need for a sale.

Key Points

•

A mortgage is actually two things—a note and a security instru-

ment.

•

Some states use a deed of trust as a security instrument.

•

Liens are prioritized by recording date.

•

Foreclosure processes differ from state to state.

What Is a Deficiency?

In order for a borrower to be held personally liable

for a foreclosure deficiency, there must be re-

course on the note. Most loans in the residential

market are with recourse. If possible, particularly

when dealing with seller-financed loans

(

see Chap-

ter 9

)

, have a corporate entity sign on the note in

your place. A corporation or limited liability com-

pany

(

LLC

)

protects its business owners from per-

sonal liability for business obligations. Upon

default, the lender’s legal recourse will be against

the property or the corporate entity, but not

against you, the business owner.

21

CHAPTER

3

Understanding the Mortgage

Loan Market

Neither a borrower nor a lender be; for loan oft loses both itself and friend.

—William Shakespeare

The mortgage business is a complicated and ever-changing indus-

try. It is important that you understand how the mortgage market

works and how the lenders make their profit. In doing so, you will

gain an appreciation of loan programs and why certain loans are

offered by certain lenders.

There are several categories of lenders that are discussed in this

chapter, and many lenders will fit in more than one category. In addi-

tion, some categories of lending are more of a lending “style” than a

lender category; this concept will make more sense after you finish

reading this chapter.

Institutional Lenders

The first broad category of distinction is institutional versus pri-

vate. Institutional lenders include commercial banks, savings and

22

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

loans or thrifts, credit unions, mortgage banking companies, pension

funds, and insurance companies. These lenders generally make loans

based on the income and credit of the borrower, and they generally

follow standard lending guidelines. Private lenders are individuals or

small companies that do not have insured depositors and are generally

not regulated by the federal government.

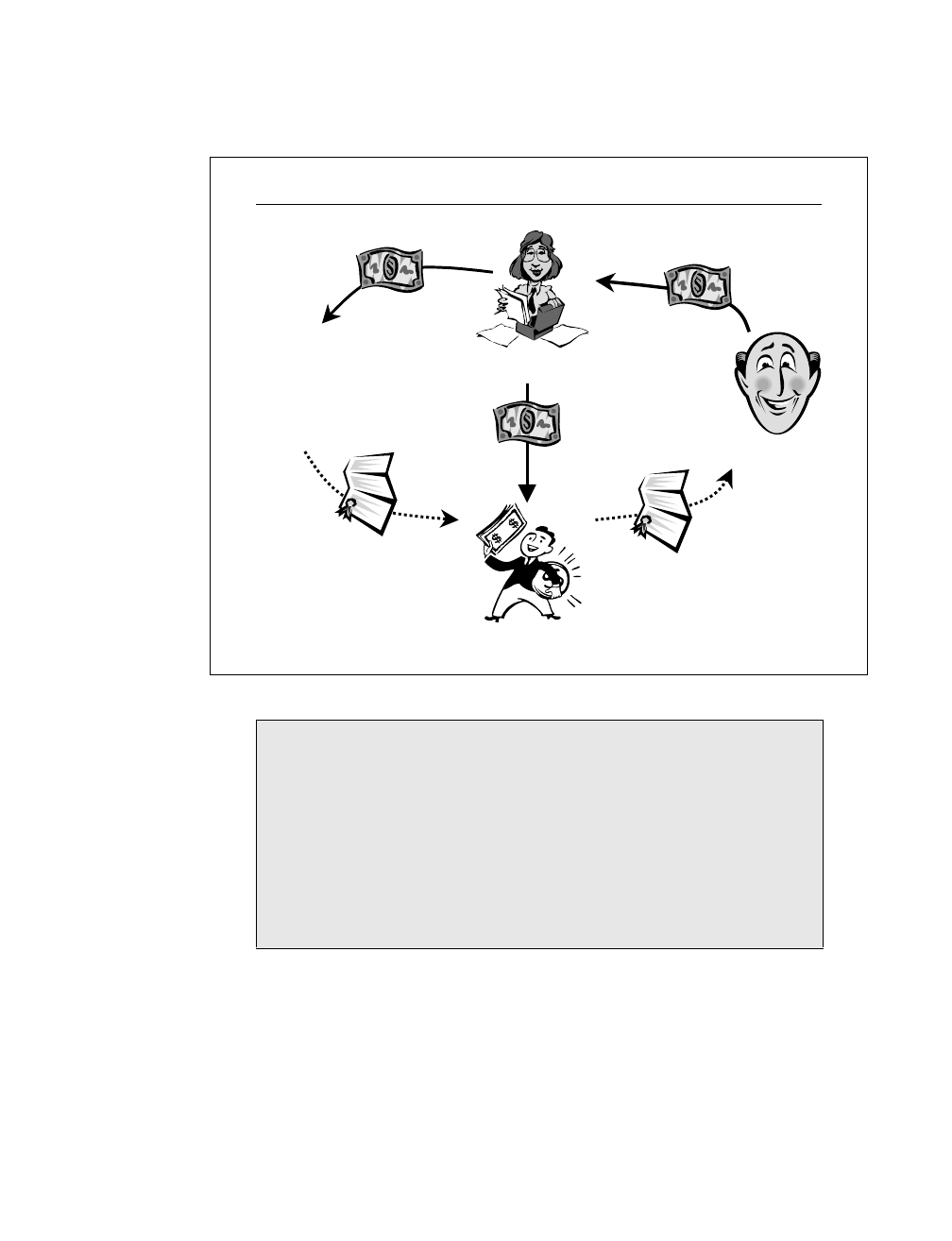

Primary versus Secondary Mortgage Markets

First, these markets should not be confused with first and second

mortgages, which were discussed in Chapter 2.

Primary mortgage

lenders

deal directly with the public. They

originate

loans, that is,

they lend money directly to the borrower. Often referred to as the

“retail” side of the business, lenders make a profit from loan process-

ing fees, not from the interest paid on the loan.

Primary mortgage lenders generally lend money to consumers,

then sell the mortgage notes

(

together in large packages, not one at a

time

)

to investors on the

secondary mortgage market

to replenish

their cash reserves.

Portfolio lenders

don’t sell their loans to the secondary market,

but rather they keep the loans as part of their portfolio

(

some lenders

sell part of their loans and keep others as part of their portfolio

)

. As

such, they don’t necessarily need to conform their loans to guidelines

established by the Federal National Mortgage Association

(

FNMA

)

or

the Federal Home Loan Corporation

(

FHLMC

)

. Small, local banks that

portfolio their loans can be an investor’s best friend, because they can

bend the rules to suit that investor’s needs.

Larger portfolio lenders can handle more loans, because they

have more funds, but they are not as flexible as the small banks. Larger

portfolio lenders can also give you an unlimited amount of loans,

whereas FNMA/FHLMC lenders have limits on the number of loans

they can give you

(

currently loans for nine properties, but these limits

often change

)

. The nation’s larger portfolio lenders include World

Savings and Washington Mutual.

3 / Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

23

The largest buyers on the secondary market are FNMA

(

or “Fannie

Mae”

)

, the Government National Mortgage Association

(

GNMA, or

“Ginnie Mae”

)

, and the FHLMC

(

or “Freddie Mac”

)

. Private financial in-

stitutions such as banks, life insurance companies, private investors,

and thrift associations also buy notes.

FNMA is a quasi-governmental agency

(

controlled by the govern-

ment but owned by private shareholders

)

that buys pools of mortgage

loans in exchange for mortgage-backed securities. GNMA is a division

of the Department of Housing and Urban Development

(

HUD

)

, a gov-

ernmental agency. Because most loans are sold on the secondary mort-

gage market to FNMA, GNMA, or FHLMC, most primary mortgage

lenders conform their loan documentation to these agencies’ guide-

lines

(

known as a “conforming” loan

)

. Although primary lenders sell

the loans on the secondary mortgage market, many of the primary

lenders will continue to collect payments and deal with the borrower,

a process called

servicing.

Mortgage Bankers versus Mortgage Brokers

Many consumers assume that “mortgage companies” are banks

that lend their own money. In fact, a company that you deal with may

be either a mortgage banker or a mortgage broker.

A

mortgage banker

is a direct lender; it lends you its own money,

although it often sells the loan to the secondary market. Mortgage

Why Sell the Loan?

Lenders sell loans for a variety of reasons. First,

they want to maximize their cash reserves. By law,

banks must have a minimum reserve, so if they

lend all of their available cash, they can’t do any

more loans. Second, they want to minimize their

risk of interest rate fluctuations in the market.

24

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

bankers

(

also known as “direct lenders”

)

sometimes retain servicing

rights as well.

A

mortgage broker

is a middleman who does the loan shopping

and analysis for the borrower and puts the lender and borrower to-

gether. Many of the lenders through which the broker finds loans do

not deal directly with the public

(

hence the expression “wholesale

lender”

)

.

Using a mortgage banker can save the fees of a middleman and

can make the loan process easier. A mortgage banker can give you

direct loan approval, whereas a broker gives you information second-

hand. However, many mortgage banks are limited in what they can of-

fer, which is essentially their own product. In addition, if you present

your loan application in a poor light, you’ve already made a bad im-

pression. I am not suggesting you lie or mislead a lender, but under-

stand that presenting a loan to a lender is like presenting your taxes to

the IRS. There are many ways to do it, all of which are valid and legal.

Using a mortgage broker allows you to present a loan application to a

different lender in a different light

(

and you are a “fresh” face

)

.

A mortgage broker charges a fee for his or her service but has

access to a wide variety of loan programs. He or she also may have

knowledge of how to present your loan application to different lend-

ers for approval. Some mortgage bankers also broker loans. As an

Loan Servicing

Loan servicing is an immensely profitable business

for mortgage banks and other lenders. Servicing

involves collecting the loan payments, accounting

for tax and insurance escrows, dealing with cus-

tomer issues, and mailing notices to the customer

and the Internal Revenue Service

(

IRS

)

. The aver-

age fee charged for servicing is about ³⁄₈ percent of

the loan amount. This may not sound like much,

but try multiplying it by a billion dollars!

3 / Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

25

investor, it is wise to have both a mortgage broker and a mortgage

banker on your team.

Conventional versus Nonconventional Loans

Conventional financing, by definition, is not insured or guaran-

teed by the federal government

(

see discussion of government loans

later in this chapter

)

. Conventional loans are generally broken into

two categories: conforming and nonconforming. A

conforming loan

is one that conforms or adheres to strict Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac loan

underwriting guidelines.

Conforming Loans

Conforming loans are a low risk to the lender, so they offer the

lowest interest rates. Conforming loans also have the strictest under-

writing guidelines.

Conforming loans have the following three basic requirements:

1.

Borrower must have a minimum of debt.

Lenders look at the

ratio of your monthly debt to income. Your regular monthly ex-

penses

(

including mortgage payments, property taxes, insur-

ance

)

should total no more than 25 percent to 28 percent of

your gross monthly income

(

called “front-end ratio”

)

. Further-

Mortgage Brokering

Keep in mind that mortgage brokering is an unli-

censed profession in many states. If there is no li-

censing agency to complain to in your state, make

sure you have personal references before you do

business with a mortgage broker.

26

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

more, your monthly expenses plus other long-term debt pay-

ments

(

e.g., student loan, automobile, alimony, child support

)

should total no more than 36 percent of your gross monthly

income

(

called “back-end ratio”

)

. These ratios can sometimes

be increased if the borrower has excellent credit or puts up a

larger down payment.

2.

Good credit rating.

You must be current on payments. Lend-

ers will also require a certain minimum credit score

(

discussed

in Chapter 4

)

.

3.

Funds to close.

You must have the requisite down payment

(

generally 20 percent of the purchase price, although lenders

often bend this rule

)

, proof of where it came from, and a few

months of cash reserves in the bank.

FHA-insured loans

(

discussed later in this chapter

)

allow higher

LTVs but are more limited in scope and are not generally available to

investors

(

discussed later in this chapter

)

.

Under writing

Underwriting is the task of applying guidelines

that provide standards for determining whether or

not a loan should be approved. Understand that

loan approval is the final step in the loan applica-

tion process before the money is handed over

(

known as “funding” a loan

)

. Note that many lend-

ers will give “preapproval” of a loan. Preapproval

is really a half-baked commitment. Until a loan is

approved in writing, the bank has no legal commit-

ment to fund. And, in many cases, loan approval is

often given with conditions attached that must be

satisfied before closing.

3 / Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

27

Private mortgage insurance.

Private mortgage insurance

(

PMI

)

requirements apply only to first mortgage loans; thus, you can get

around PMI requirements by borrowing a first and second mortgage

loan. So long as the first mortgage loan is less than 80 percent loan-to-

value, PMI is not required. However, the second mortgage loan may

have a high interest rate, so that the blending of the interest rate on

the first and second mortgage loans exceeds what you would be pay-

ing with a first mortgage and PMI. Use a calculator to figure out which

is more profitable for you

(

the formula for interest rate blending is dis-

cussed in Chapter 5

)

.

One way around the large down payment is to purchase PMI. Also

known as “mortgage guaranty insurance,” PMI will cover the lender’s

additional risk for a high loan-to-value ratio

(

LTV

)

program. The in-

surer will reimburse the lender for its additional risk of the high LTV.

PMI should not be confused with mortgage life insurance, which

pays the borrower’s loan balance in full when he or she dies

(

not rec-

ommended—regular term life insurance is a better deal for the money

)

.

What Is the Loan-to-Value

(

LT V

)

Ratio?

Loan-to-value ratio is the percentage of the value of

the property the lender is willing to lend. For ex-

ample, if the property is worth $100,000, an 80

percent LTV loan will be for $80,000. Note that

LTV is not the same as loan-to-purchase price, be-

cause the purchase price may be more or less than

the appraised value

(

discussed in more detail in

Chapter 5

)

.

28

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Nonconforming Loans

Nonconforming loans

have no set guidelines and vary widely

from lender to lender. In fact, lenders often change their own noncon-

forming guidelines from month to month.

Nonconforming loans are also known as “subprime” loans, be-

cause the target customer

(

borrower

)

has credit and/or income verifi-

cation that is less than perfect. The subprime loans are often rated

according to the creditworthiness of the borrower—“A,” “B,” “C,”

or “D.”

An “A” credit borrower has had few or no credit problems within

the past two years, with the exception of a late payment or two with

a good explanation. A “C” credit borrower may have a history of sev-

eral late payments and a bankruptcy.

The subprime loan business has grown enormously over the past

ten years, particularly in the refinance business and with investor

loans. Every lender has its own criteria for subprime loans, so it is

impossible to list every loan program available on the market. Suffice

it to say, the guidelines for subprime loans are much more lax than

they are for conforming loans.

Government Loan Programs

The federal government and state government sponsor loan pro-

grams to encourage home ownership. Most of the loan programs are

geared towards low-income neighborhoods and first-time homebuyers.

If you are dealing in low-income properties, you should be aware of

these guidelines if you intend to sell properties to these target home-

buyers. Also, some of these programs are geared to investors as well.

3 / Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

29

Federal Housing Administration Loans

HUD is the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

an executive branch of the federal government. The Federal Housing

Administration

(

FHA

)

is an arm of HUD that administers loan pro-

grams. HUD does not lend money but rather insures lenders that make

high LTV loans. Because high LTV loans are risky for lenders, the FHA-

insured loan programs cover the additional risk. Not all lenders can

make FHA-insured loans; they must be approved by HUD.

The most common FHA loan program is the 203

(

b

)

program,

designed for first-time homebuyers. This program allows an owner-

occupant to put just 3 percent down and borrow 97 percent loan-to-

value. This program is for owner-occupied

(

noninvestor

)

properties,

but investors should be familiar with the program because they may

wish to sell a property to a buyer who may use the program.

The two most common HUD loans available for investors are the

Title 1 Loan and the 203

(

k

)

loan.

Confusion of Terms

Some mortgage professionals will use the expres-

sion “conventional” to mean “conforming,” and

vice-versa. So, when a mortgage broker says that

“you’ll have to go with a nonconforming loan,” the

loan documentation may still have to substantially

conform with FNMA guidelines. In fact, even loans

that do not conform with FNMA or conventional

standards are underwritten on FNMA “paper”

(

the

actual note, mortgage, and other related docu-

ments

)

. Lenders do this with the intention of even-

tually selling the paper, even if it may begin as a

portfolio loan.

30

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Title 1 loan.

The Title 1 loan insures loans of up to $25,000 for

light to moderate rehab of single-family properties, or $12,000 per

unit for a maximum of $60,000 on multifamily properties. The interest

rates on these loans are generally market rate, although local participa-

tion by state or municipal agencies may reduce the rate

(

see below

)

.

An interesting note on Title 1 loans is that it is not limited to own-

ers of the property. A lessee or equitable owner under an installment

land contract

(

discussed in Chapter 9

)

may qualify for the loan.

FHA 203

(

k

)

loan.

The 203

(

k

)

program is for an investor who

wants to live in the home while rehabbing it. It allows the investor-

occupant to borrow money for the purchase or refinance of a home

as well as for the rehab costs. It is an excellent alternative to the tradi-

tional route for these investors, which is to buy a property with a tem-

porary

(

“bridge”

)

loan, fix the property, then refinance it

(

many

lenders won’t offer attractive, long-term financing on rehab proper-

ties

)

.

The 203

(

k

)

loan can be for up to the value of the property plus

anticipated improvement costs, or 110 percent of the value of the

property, whichever is less. The rehab cost must be at least $5,000,

but there is no limit to the size of the rehab

(

although it cannot be

used for new construction, that is, the basic foundation of the prop-

erty must be used, even if the building is razed

)

. The program can be

used for condominiums, provided that the condo project is otherwise

FHA qualified. Cooperative apartments, popular in New York and

California, are not eligible.

The Department of Veterans Affairs

The Department of Veterans Affairs

(

VA

)

guarantees certain loan

programs for eligible veterans. As an occupant, an eligible veteran can

borrow up to 100 percent of the purchase price of the property. When

a borrower with a VA-guaranteed loan cannot meet the payments, the

lender forecloses on the home. The lender next looks to the VA to

cover the loss for its guarantee, and the VA takes ownership of the

home. The VA then offers the property for sale to the public.

3 / Understanding the Mortgage Loan Market

31

State and Local Loan Programs

Many states and localities sponsor programs to help first-time

homebuyers qualify for mortgage loans. The programs are aimed at im-

proving low-income neighborhoods by increasing the number of own-

ers versus renters in the area. Most of these programs are for owner-

occupants, not investors, but it may also help to know about these pro-

grams when you are selling homes.

Some state and local programs work in conjunction with HUD

programs, such as Title 1 loans. Contact your state or city department

of housing for more information on locally sponsored loan programs.

A list of links to state programs can be found at

<

www.hsh.com/pam

phlets/state_hfas.html

>

.

Commercial Lenders

Most of the discussion so far has been about financing of single-

family homes and small multifamily residential homes. What about

large multifamily projects and commercial projects, such as shopping

centers, strip malls, and office buildings? Many of the same concepts

do apply, except for the financing guidelines.

Commercial lenders generally do not have industry-wide loan cri-

teria. Instead, each lender has its own criteria and will review loans

on a project-by-project basis. Lenders will look at the experience of

Condominium Financing Pitfalls

Condominiums can be difficult to finance in gen-

eral, as compared to single-family homes. In gener-

al, stay away from units in developments that have

a large concentration of investor-owners. Condo

developments that have a 50 percent or more con-

centration of nonoccupant owners are very diffi-

cult to finance through institutional lenders.

32

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

the investor as well as the income and expenses of the particular col-

lateral. In other words, commercial lenders are more concerned with

whether the property will generate enough income to pay the loan,

not whether the borrower has good credit

(

although a borrower with

poor credit will generally have a hard time getting any type of loan

from an institutional lender

)

. A commercial appraisal is required,

which is more detailed and expensive than a residential appraisal. A

commercial loan will require the borrower to have a substantial

reserve of cash to handle vacancies.

Commercial loans also can be made for residential buildings of

five units or more, but there is a minimum loan amount required by

each lender

(

generally a $300,000 to $500,000, depending on the

property values in your marketplace

)

. Oddly enough, multimillion dol-

lar loans are often made without recourse to the borrower. In other

words, if the project fails, the borrower

(

often a corporate entity

)

is

not liable for the debt. The lender’s sole recourse is to foreclose against

the property. For this reason, the lender is more concerned with the

property than the borrower.

Key Points

•

Most lenders sell their loans to the secondary market.

•

Loans come in three basic categories: conforming, noncon-

forming, and government.

•

The government does not lend money, but rather it guarantees

loans.

•

Commercial lenders look to the property rather than the

borrower.

33

CHAPTER

4

Working with Lenders

Except for the con men borrowing money they shouldn’t get and the widows who have

to visit with the handsome young men in the trust department, no sane person ever

enjoyed visiting a bank.

—Martin Meyer

Now that you understand how loans and the mortgage market

works, you can begin to understand how to approach financing. In

Chapter 3, we discussed a variety of loan

programs

that differ based

on the lender, the type of property, and the borrower. We will now

turn to loan

types

that are generally available in most of the loan pro-

grams discussed thus far and the advantages and disadvantages of

each. Before doing so, let’s explore some of the relevant issues we

need to consider when borrowing money.

Interest Rate

The cost of borrowing money, that is, the interest rate, is one of

the most important factors. As discussed in Chapter 1, interest rates

affect monthly payments, which in turn affect how much you can

34

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

afford to pay for a property. It may also affect cash flow, which affects

your decision to hold or sell property.

Loan Amortization

There are many different ways a loan can be structured as far as

interest payments go. The most common ways are simple interest and

amortized.

As discussed in Chapter 1, a simple interest loan is calculated by

multiplying the loan balance by the interest rate. So, for example, a

$100,000 loan at 12 percent interest would be $12,000 per year, or

$1,000 per month. The payments here, of course, represent interest-

only, so the principal amount of the loan does not change.

An amortized loan is slightly more involved. The actual mathe-

matical formula is beyond a book like this, so we’ve provided a sample

interest rate table in Appendix A. However, you can find a thousand

Internet Web sites that will do the calculations instantly online

(

try

mine at

<

www.legalwiz.com

>

—click on “calculators”

)

. The amortiza-

tion method breaks down payments over a number of years, with the

payment remaining constant each month. However, the interest is cal-

culated on the remaining balance, so the amount of each monthly pay-

ment that accounts for principal and interest changes. For the most

part, the more payments you make, the more you decrease the amount

of principal owed

(

the amount of the loan still left to pay

)

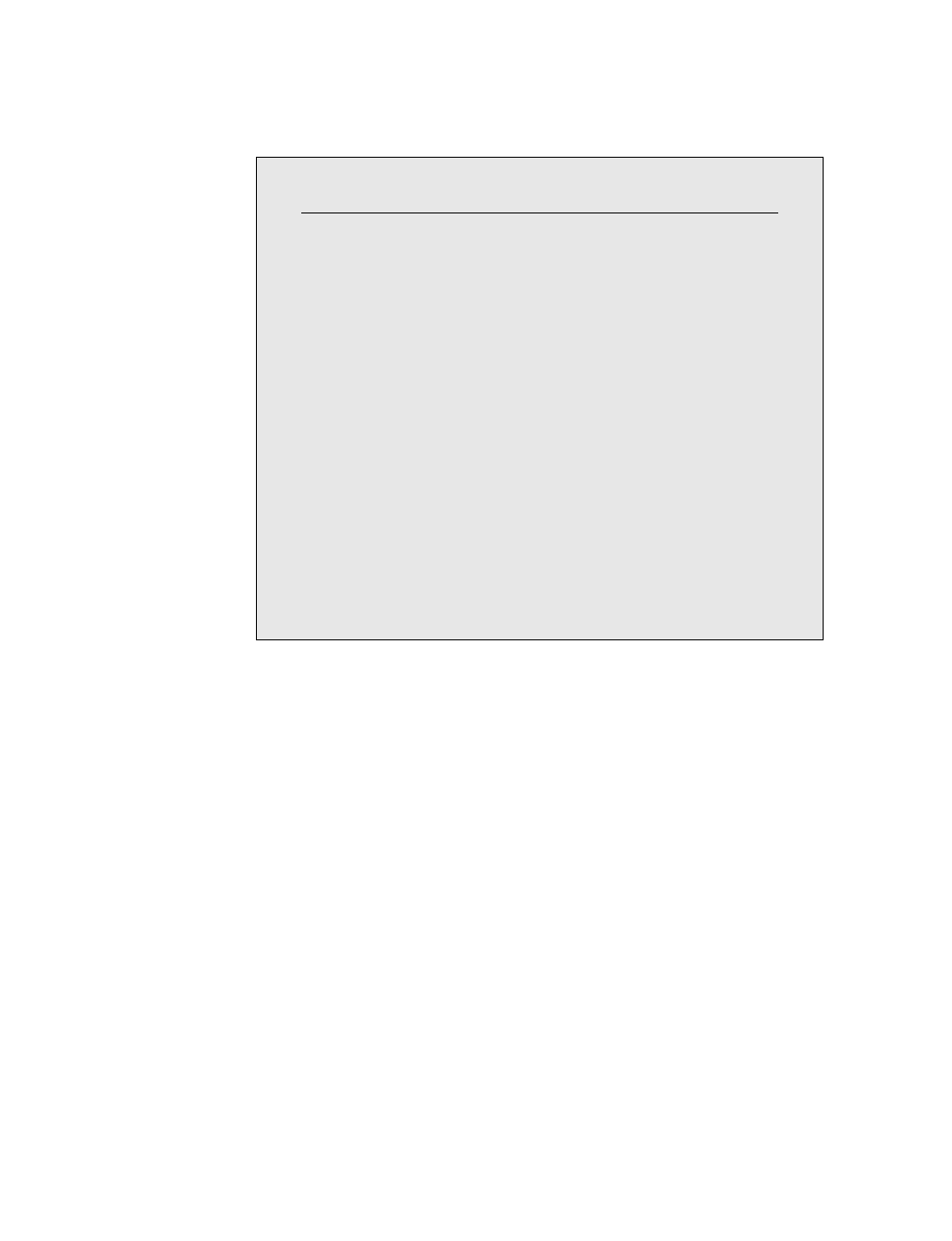

. See Figure

4.1.

The loan

term

or duration is important to figuring your payment.

By custom, most loans are amortized over 30 years or 360 monthly

payments. The second most common loan term is 15 years. The pay-

ments on a 15-year amortization are higher each month, but you pay

the loan off faster and thus pay less interest in the long run.

4/Working with Lenders

35

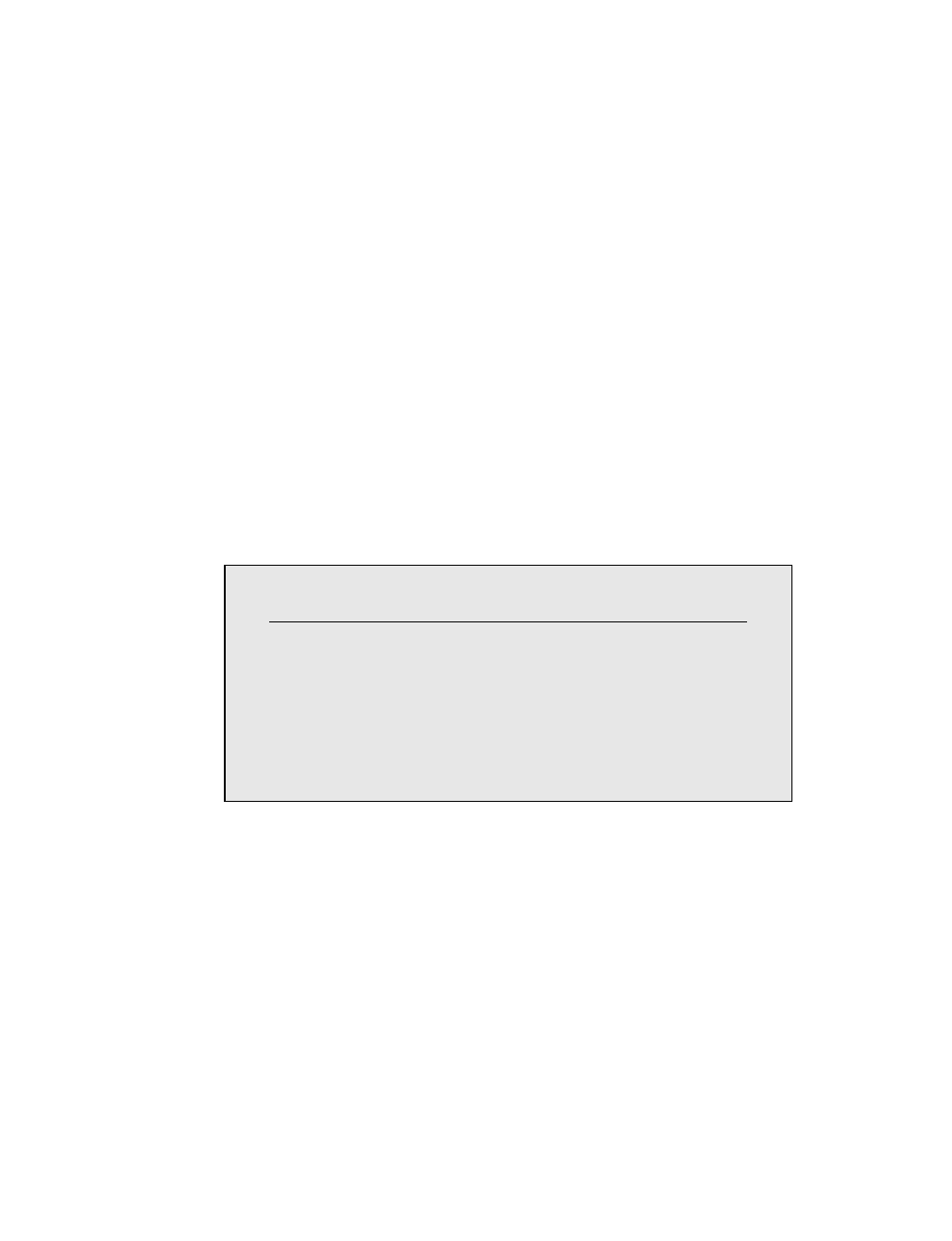

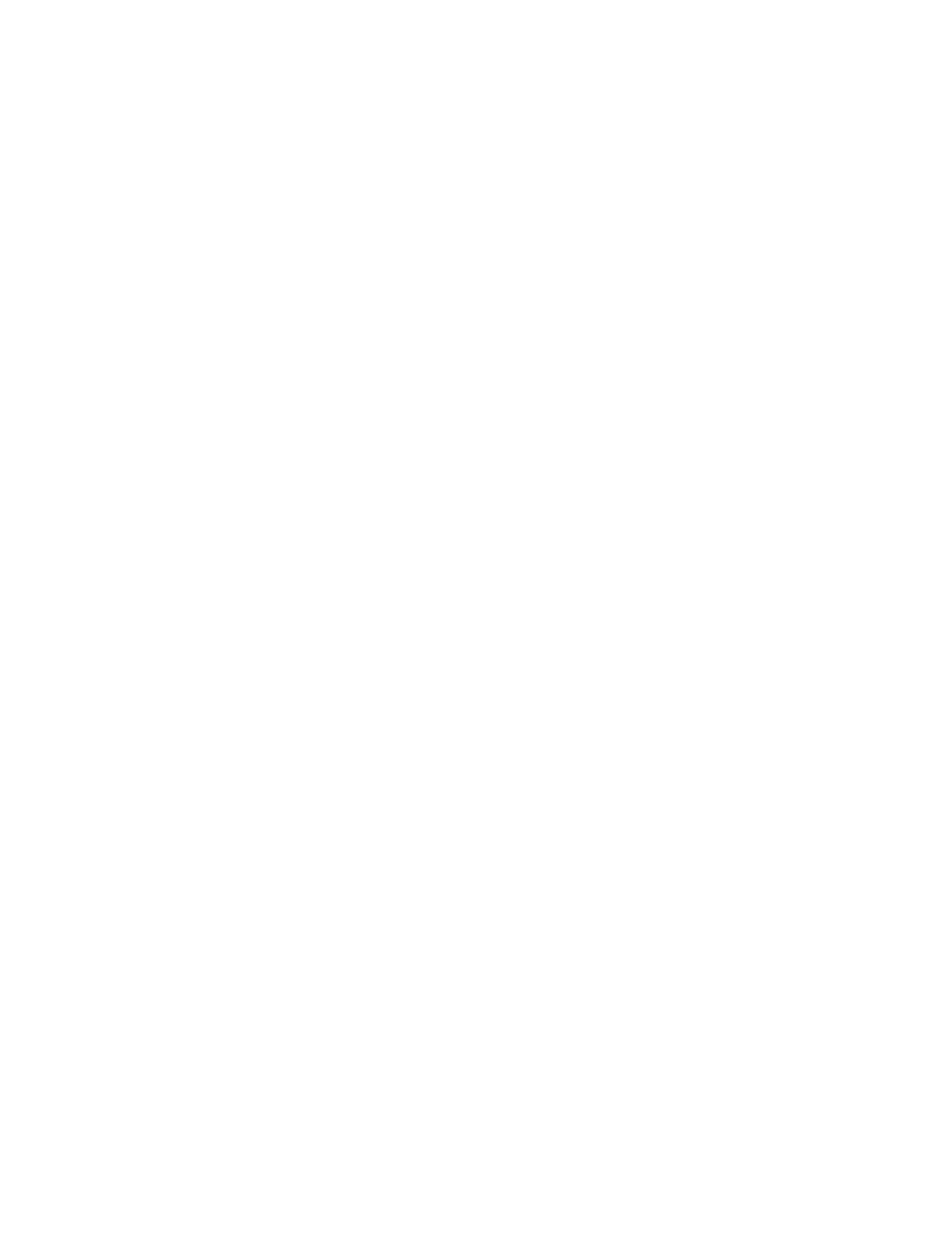

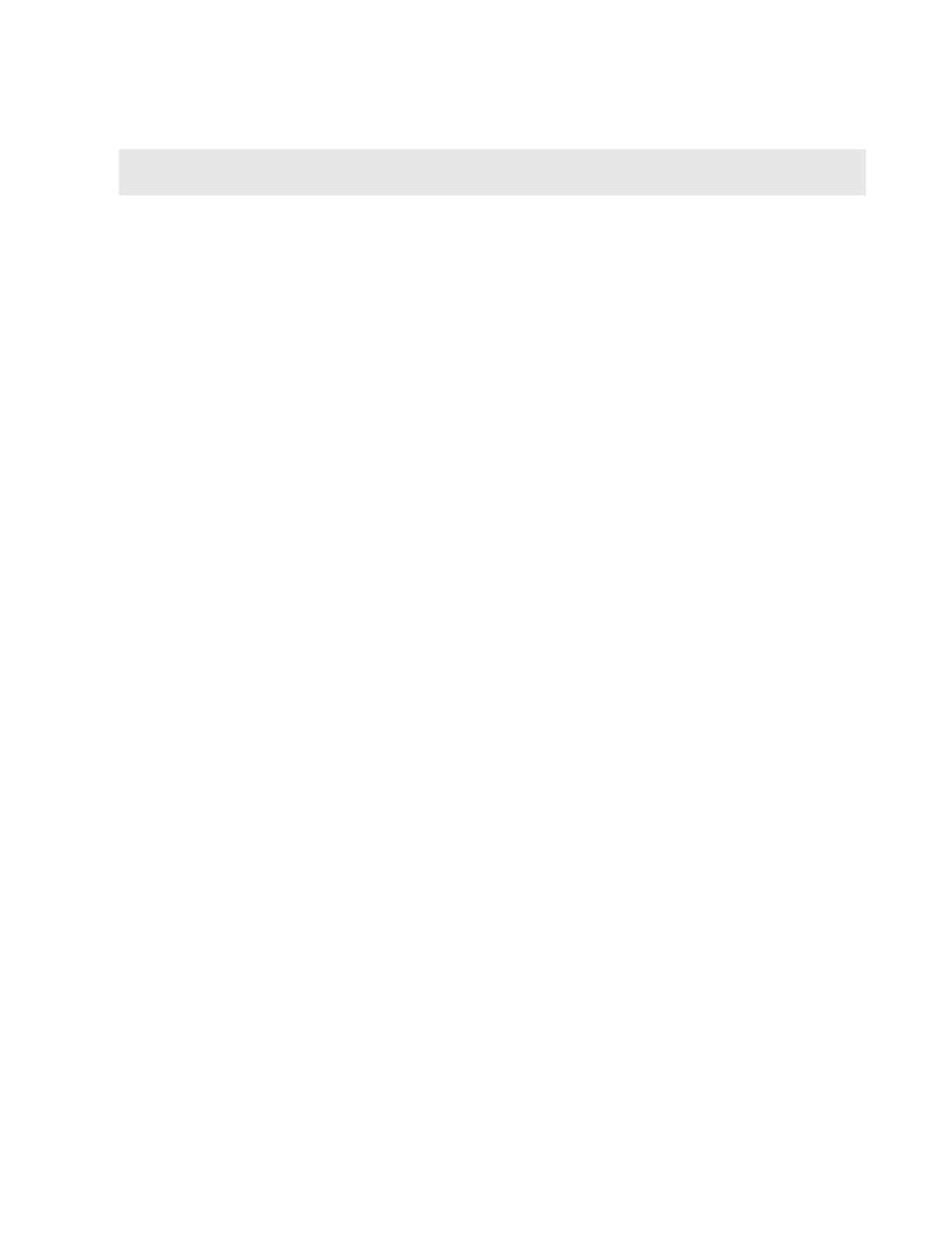

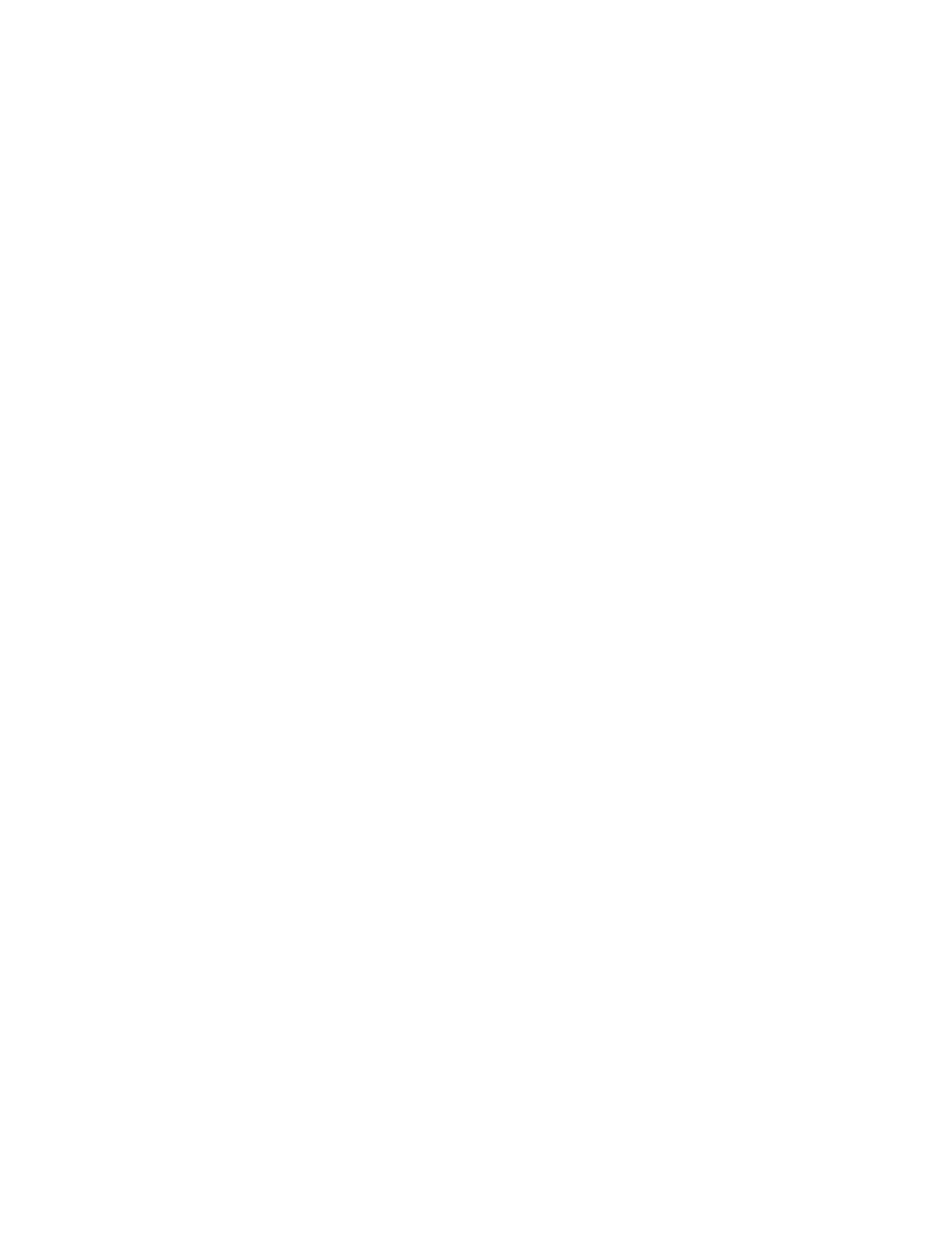

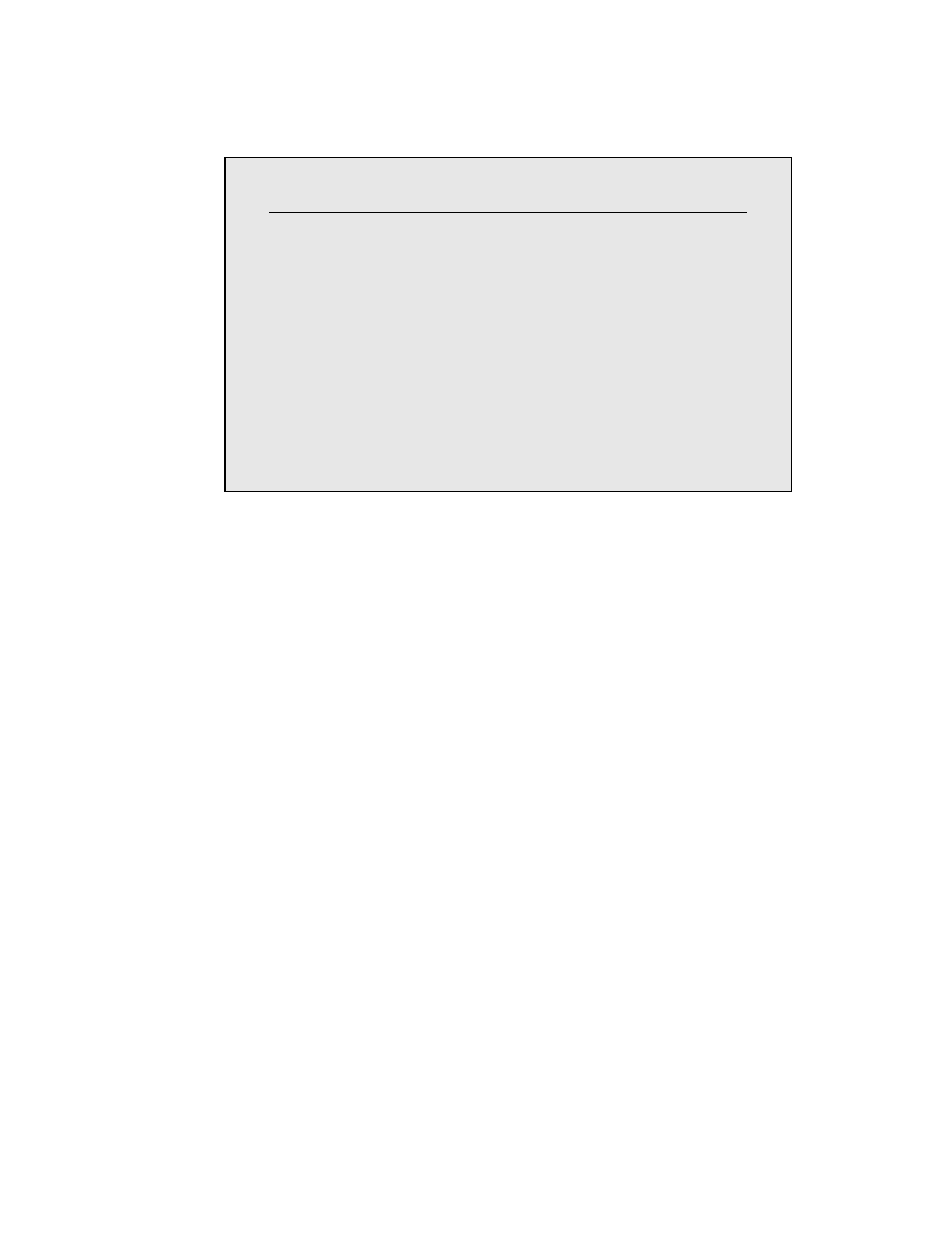

FIGURE 4.1

Amortization of $100,000 Loan at 8% Interest Over 30 Years

Payment # Date Payment Interest Principal Loan Balance

1 02-01-2003 733.76 666.67 67.09 99,932.91

2 03-01-2003 733.76 666.22 67.54 99,865.37

3 04-01-2003 733.76 665.77 67.99 99,797.38

4 05-01-2003 733.76 665.32 68.44 99,728.94

5 06-01-2003 733.76 664.86 68.90 99,660.04

6 07-01-2003 733.76 664.40 69.36 99,590.68

7 08-01-2003 733.76 663.94 69.82 99,520.86

8 09-01-2003 733.76 663.47 70.29 99,450.57

9 10-01-2003 733.76 663.00 70.76 99,379.81

10 11-01-2003 733.76 662.53 71.23 99,308.58

11 12-01-2003 733.76 662.06 71.70 99,236.88

12 01-01-2004 733.76 661.58 72.18 99,164.70

13 02-01-2004 733.76 661.10 72.66 99,092.04

14 03-01-2004 733.76 660.61 73.15 99,018.89

15 04-01-2004 733.76 660.13 73.63 98,945.26

16 05-01-2004 733.76 659.64 74.12 99,871.14

17 06-01-2004 733.76 659.14 74.62 98,796.52

18 07-01-2004 733.76 658.64 75.12 98,721.40

19 08-01-2004 733.76 658.14 75.62 98,645.78

20 09-01-2004 733.76 657.64 76.12 98,569.66

21 10-01-2004 733.76 657.13 76.63 98,493.03

22 11-01-2004 733.76 656.62 77.14 98,415.89

23 12-01-2004 733.76 656.11 77.65 98,338.24

24 01-01-2005 733.76 655.59 78.17 98,260.07

25 02-01-2005 733.76 655.07 78.69 98,181.18

26 03-01-2005 733.76 654.54 79.22 98,102.16

27 04-01-2005 733.76 654.01 79.75 98,022.41

28 05-01-2005 733.76 653.48 80.28 97,942.13

29 06-01-2005 733.76 652.95 80.81 97,861.32

30 07-01-2005 733.76 652.41 81.35 97,779.97

31 08-01-2005 733.76 651.87 81.89 97,698.08

32 09-01-2005 733.76 651.32 82.44 97,615.64

33 10-01-2005 733.76 650.77 82.99 97,532.65

34 11-01-2005 733.76 650.22 83.54 97,449.11

35 12-01-2005 733.76 649.66 84.10 97,365.01

36 01-01-2006 733.76 649.10 84.66 97,280.35

37 02-01-2006 733.76 648.54 85.22 97,195.13

38 03-01-2006 733.76 647.97 85.79 97,109.34

39 04-01-2006 733.76 647.40 86.36 97,022.98

40 05-01-2006 733.76 646.82 86.94 96,936.04

41 06-01-2006 733.76 646.24 87.52 96,848.52

42 07-01-2006 733.76 645.66 88.10 96,760.42

43 08-01-2006 733.76 645.07 88.69 96,671.73

44 09-01-2006 733.76 644.48 89.28 96,582.45

45 10-01-2006 733.76 643.88 89.88 96,492.57

46 11-01-2006 733.76 643.28 90.48 96,402.09

349 02-01-2032 733.76 56.28 677.48 7,764.01

350 03-01-2032 733.76 51.76 682.00 7,082.01

351 04-01-2032 733.76 47.21 686.55 6,395.46

352 05-01-2032 733.76 42.64 691.12 5,704.34

353 06-01-2032 733.76 38.03 695.73 5,008.61

354 07-01-2032 733.76 33.39 700.37 4,308.24

355 08-01-2032 733.76 28.72 705.04 3,603.20

356 09-01-2032 733.76 24.02 709.74 2,893.46

357 10-01-2032 733.76 19.29 714,47 2,178.99

358 11-01-2032 733.76 14.53 719.23 1,459.76

359 12-01-2032 733.76 9.73 724.03 735.73

36

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

15-Year Amortization versus 30-Year Amortization

In general, 15-year loans tend to have a slightly lower interest

rate. In addition, you reach your financial goal of “free and clear”

faster. However, there are three downsides to the 15-year loan. The

first is that you are obligated to a higher payment that reduces your

cash flow. Second, the higher monthly obligation appears on your

credit report, which affects your debt ratios and thus your ability to

borrow more money

(

discussed later in this chapter

)

. Third, your

monthly payment is less interest and more principal. While this may

sound like a good thing, it doesn’t give you the same tax benefits; in-

terest payments are deductible, principal payments are not.

Unless the interest rate on the 15-year note is significantly lower,

opt for the 30-year note. You can accomplish the faster principal pay

down by making extra interest payments to the lender.

Example:

On a $100,000 loan amortized at 8% over 30

years, your payment is $733.76. If you make an additional

principal payment each month of $100, the loan would be

fully amortized in just over 20 years, saving you $62,468.87

in interest.

You can use a financial calculator to calculate how much extra

you need to pay each month to reduce the loan term

(

again, try mine

at

<

www.legalwiz.com

>

—click on “calculators”

)

. And, of course,

Three Negatives to a 15-Year Loan

1. Higher monthly payments

2. Increased debt ratios

3. Less of a tax deduction

☛

4/Working with Lenders

37

when times are hard and the property is vacant, you aren’t obligated

to make the higher payment.

Balloon Mortgage

A

balloon

is a premature end to a loan’s life. For example, a loan

could call for interest-only payments for three years, then be due in

full at the end of three years. Or, a loan could be amortized over 30

years, with the principal balance remaining due in five years. When

the loan balloon payment becomes due, the borrower must pay the

full amount or face foreclosure.

A balloon provision can be risky for the borrower, but if used

with common sense, it may work effectively by satisfying the lender’s

needs. Balloon notes are often used by builders as a short-term financ-

ing tool. These types of loans are also known as “bridge” or “mezza-

nine” financing.

Biweekly Mortgage Payment Programs

An entire multilevel marketing business has been

made out of the selling people the idea of a bi-

weekly mortgage program. Basically, if you pay

your loan every two weeks rather than monthly,

you make two extra payments per year. With the

additional payments going towards principal, the

debt amortizes faster. Before plunking down sev-

eral hundred dollars to a third party to do this for

you, ask your lender. Many lenders will set up a

direct deposit program from your bank account

for biweekly payments.

38

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Reverse Amortization

Regular amortization means as you make payments the loan bal-

ance decreases. Reverse amortization means the more you pay, the

more you owe. How is that possible? Simple—by making a lower pay-

ment each month than would be possible for the stated interest rate.

A reverse amortization loan increases your cash flow but also increases

your risk because you will owe more in the future. If you bought the

property below market, a reverse amortization loan may make sense,

especially if real estate prices are rising rapidly

(

another option may

be a variable rate loan, discussed later in this chapter

)

.

Property Taxes and Insurance Escrows

In addition to monthly principal and interest payments on your

loan, you’ll have to figure on paying property taxes and hazard insur-

ance. Many lenders won’t trust you to make these payments on your

own, especially if you are borrowing at a high loan-to-value

(

80 per-

cent LTV or higher

)

. Lenders estimate the annual payments for taxes

and insurance, then collect these payments from you monthly into a

reserve account

(

called an “escrow” or “impound account”

)

. The

lender then makes the disbursements directly to the county tax collec-

tor and your insurance company on an annual basis. Thus, the total

amount collected each month consists of principal and interest pay-

ments on the note, plus taxes and insurance—hence the acronym

PITI.

Reverse Amortization Loans for the Elderly

Many mortgage banks are advertising reverse am-

ortization loans to elderly homeowners as a way to

reduce their monthly payments. These loan pro-

grams are not intended for investors as described

above.

4/Working with Lenders

39

Loan Costs

Origination Fee

The cost of a loan is as important as the interest rate. Lenders and

mortgage brokers charge various fees for giving you a loan

(

and you

thought they just made money on the interest rates!

)

. Traditionally,

the most expensive part of the loan package is the loan origination

fee. The fee is expressed in

points,

that is, a percentage of the loan

amount: 1 point = 1 percent. So, for example, if a lender charges a

“1 point origination fee” on a $100,000 loan, you would pay 1 per-

cent, or $1,000, as a fee.

Discount Points

Another built-in profit center is the charging of “discount points.”

The lender will offer you a lower interest rate for the payment of

money up front. Thus, if you want your interest rate to be lower, you

can “buy down” the rate by paying ¹⁄₂ point

(

percent

)

or more of the

loan up front. Buying down the rate only makes sense if you plan on

keeping the loan for a long time; otherwise buying down the interest

rate is a waste of money.

Borrowers nowadays are smarter and try to beat the banks at

their own game by refusing to pay points. Banks even advertise “no

cost” loans, that is, loans with no discount points or origination fees.

Yield Spread Premiums: The Little Secret Your Lender

Doesn’t Want You to Know

The lower the interest rate, the better off you are, or are you?

Lenders advertise “wholesale” interest rates on a daily basis to mort-

gage brokers, who then advertise rates to their customers. This whole-

sale interest rate can be marked up on the retail side by the mortgage

broker.

40

FINANCING SECRETS OF A MILLIONAIRE REAL ESTATE INVESTOR

Example:

Say, for example, your mortgage broker offers you

an interest rate of 7.25% on a $200,000, 30-year fixed loan.

The monthly payment on this loan would be $1,364.35,

which is acceptable to you. However, the wholesale rate of-

fered by the lender may be 7.00%, which is $1,330.60 per

month. This difference may not seem like much, but over 30

years, it amounts to about $12,000 in additional interest paid.

The mortgage broker receives a “bonus” back from the

lender for the additional interest earned. This bonus is called

a yield spread premium

(

YSP

)

because it represents the addi-

tional yield earned by the lender for the higher interest rate.

Loan Junk Fees

Even without points and at par

(

no markup on the interest rate

)

,

there is no such thing as a no-cost loan. Lenders sneak in their profit

by disguising other fees, such as the following:

•

Administrative Review

•

Underwriting Charge

•

Documentation Fee

Are Yield Spread Premiums Legal?

At this time,YSPs are legal as long as they are dis-

closed on the loan documents. Although it is not

technically a fee to the borrower, YSPs are not ille-

gal “kickbacks” to the mortgage broker either. You