Microsoft Word 2007 For Dummies

Word 2007

FOR

DUMmIES

‰

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page i

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page ii

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page ii

Word 2007 For Dummies

®

Published by

Wiley Publishing, Inc.

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774

www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted

under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis-

sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright

Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to

the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475

Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www.

wiley.com/go/permissions.

Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the

Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade

dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United

States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the

property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor

mentioned in this book.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF W

ARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REP-

RESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CON-

TENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT

LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CRE-

ATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CON-

TAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE

UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR

OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A

COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE

AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION

OR WEBSITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FUR-

THER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFOR-

MATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE.

FURTHER, READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT INTERNET WEBSITES LISTED IN THIS WORK MAY HAVE

CHANGED OR DISAPPEARED BETWEEN WHEN THIS WORK WAS WRITTEN AND WHEN IT IS READ.

For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care

Department within the U.S. at 800-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002.

For technical support, please visit www.wiley.com/techsupport.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may

not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2006934826

ISBN-13: 978-0-470-03658-7

ISBN-10: 0-470-03658-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

1B/QV/RS/QW/IN

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page iv

About the Author

After physically destroying three typewriters, Dan Gookin bought his first

computer in 1982 at the urging of the guy in the typewriter repair shop.

Contrary to his prejudices, Dan quickly discovered that computers were

about more than math, and he quickly took to the quirky little devices.

Twenty-five years later, Mr. Gookin has written over 100 books about comput-

ers and high tech and gone through more than 50 computers, including a

dozen or so laptops and portables. He has achieved fame as one of the first

computer radio talk show hosts, the editor of a magazine, a national technol-

ogy spokesman, and an occasional actor on the community theater stage.

Dan still considers himself a writer and computer “guru” whose job it is to

remind everyone that computers are not to be taken too seriously. His

approach to computers is light and humorous, yet very informative. He

knows that the complex beasts are important and can do a great deal to help

people become productive and successful. Dan mixes his vast knowledge of

computers with a unique, dry sense of humor that keeps everyone informed —

and awake. His favorite quote is “Computers are a notoriously dull subject,

but that doesn’t mean I have to write about them that way.”

Dan Gookin’s most recent books are PCs For Dummies, 10th Edition, Laptops

For Dummies, 2nd Edition, and some new titles he can’t yet discuss under

threat of death. He holds a degree in communications/visual arts from UCSD.

Dan dwells in North Idaho, where he enjoys woodworking, music, theater,

riding his bicycle, and spending time with the lads.

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page v

Publisher’s Acknowledgments

We’re proud of this book; please send us your comments through our online registration form

located at www.dummies.com/register/.

Some of the people who helped bring this book to market include the following:

Acquisitions, Editorial, and

Media Development

Project Editor: Paul Levesque

Acquisitions Editor: Greg Croy

Copy Editor: Rebecca Whitney

Technical Editor: Lee Musick

Editorial Manager: Leah Cameron

Media Development Specialists: Angela Denny,

Kate Jenkins, Steven Kudirka, Kit Malone

Media Development Coordinator:

Laura Atkinson

Media Project Supervisor: Laura Moss

Media Development Manager:

Laura VanWinkle

Editorial Assistant: Amanda Foxworth

Sr. Editorial Assistant: Cherie Case

Cartoons: Rich Tennant (

www.the5thwave.com)

Composition Services

Project Coordinator: Adrienne Martinez

Layout and Graphics: Lavonne Cook,

Denny Hager, Stephanie D. Jumper,

Clint Lahnen, Barbara Moore,

Barry Offringa, Lynsey Osborn,

Erin Zeltner

Proofreaders: Laura Albert,

Christine Pingleton, Techbooks

Indexer: Techbooks

Anniversary Logo Design: Richard Pacifico

Special Help: Mary Lagu

Publishing and Editorial for Technology Dummies

Richard Swadley, Vice President and Executive Group Publisher

Andy Cummings, Vice President and Publisher

Mary Bednarek, Executive Acquisitions Director

Mary C. Corder, Editorial Director

Publishing for Consumer Dummies

Diane Graves Steele, Vice President and Publisher

Joyce Pepple, Acquisitions Director

Composition Services

Gerry Fahey, Vice President of Production Services

Debbie Stailey, Director of Composition Services

01_036583 ffirs_2.qxp 12/15/06 10:14 AM Page vi

Contents at a Glance

Introduction .................................................................1

Part I: Hello, Word!......................................................9

Chapter 1: Word Hokey-Pokey ........................................................................................11

Chapter 2: Making Friends with the Keyboard.............................................................25

Chapter 3: A Quick Guide to Word (For the Impatient)...............................................35

Part II: Word Processing Basics...................................45

Chapter 4: Moving Around a Document Hither, Thither, and Yon .............................47

Chapter 5: Editing Text ....................................................................................................55

Chapter 6: Find and Replace ...........................................................................................65

Chapter 7: Text Blocks, Stumbling Blocks, Writer’s Blocks ........................................79

Chapter 8: Proofing Your Document (Spelling and Grammar) ...................................95

Chapter 9: Documents and Files...................................................................................111

Chapter 10: The Printer, the Paper, the Document Maker ........................................125

Part III: Formatting ..................................................137

Chapter 11: Formatting Text .........................................................................................139

Chapter 12: Formatting Paragraphs.............................................................................153

Chapter 13: Setting Tabs................................................................................................167

Chapter 14: Formatting Pages.......................................................................................183

Chapter 15: Formatting Documents.............................................................................197

Chapter 16: The Styles of Word ....................................................................................211

Chapter 17: Themes and Templates ............................................................................227

Chapter 18: Misc. Formatting Stuff...............................................................................239

Part IV: Making Your Document

All Fancy-Schmancy.................................................251

Chapter 19: Borders, Boxes, and Background Color .................................................253

Chapter 20: Turning the Tables ....................................................................................261

Chapter 21: Carousing with Columns ..........................................................................273

Chapter 22: I Love Lists .................................................................................................279

Chapter 23: Going Graphical.........................................................................................289

Chapter 24: Stick

This in Your Document....................................................................301

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page vii

Part V: What Else Is Left? .........................................309

Chapter 25: Multiple Documents, Multiple Windows,

Multiple Formats, Multiple Madness.........................................................................311

Chapter 26: Other Ways of Viewing a Document........................................................321

Chapter 27: Working This Out Together......................................................................331

Chapter 28: Merrily We Mail Merge..............................................................................339

Chapter 29: Labels of Love............................................................................................351

Chapter 30: Customizing Word .....................................................................................357

Part VI: The Part of Tens ...........................................365

Chapter 31: The Ten Commandments of Word...........................................................367

Chapter 32: Ten Cool Tricks..........................................................................................371

Chapter 33: Ten Odd Things .........................................................................................379

Chapter 34: Ten Avuncular Suggestions......................................................................385

Index .......................................................................389

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page viii

Table of Contents

Introduction..................................................................1

What’s New in Word 2007?..............................................................................1

About This Book...............................................................................................2

How to Use This Book .....................................................................................3

Foolish Assumptions .......................................................................................4

How This Book Is Organized...........................................................................4

Part I: Hello, Word!..................................................................................5

Part II: Word Processing Basics............................................................5

Part III: Formatting .................................................................................5

Part IV: Making Your Document All Fancy-Schmancy........................5

Part V: What Else Is Left?.......................................................................5

Part VI: The Part of Tens .......................................................................5

What’s Not Here ...............................................................................................6

Icons Used in This Book..................................................................................6

Where to Go from Here....................................................................................7

Part I: Hello, Word!.......................................................9

Chapter 1: Word Hokey-Pokey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

How Do I Start Word? Let Me Count the Ways. . . . ....................................11

The good, yet unimaginative, way to start Word .............................12

The better and best ways to start Word............................................13

Starting Word by opening a document..............................................15

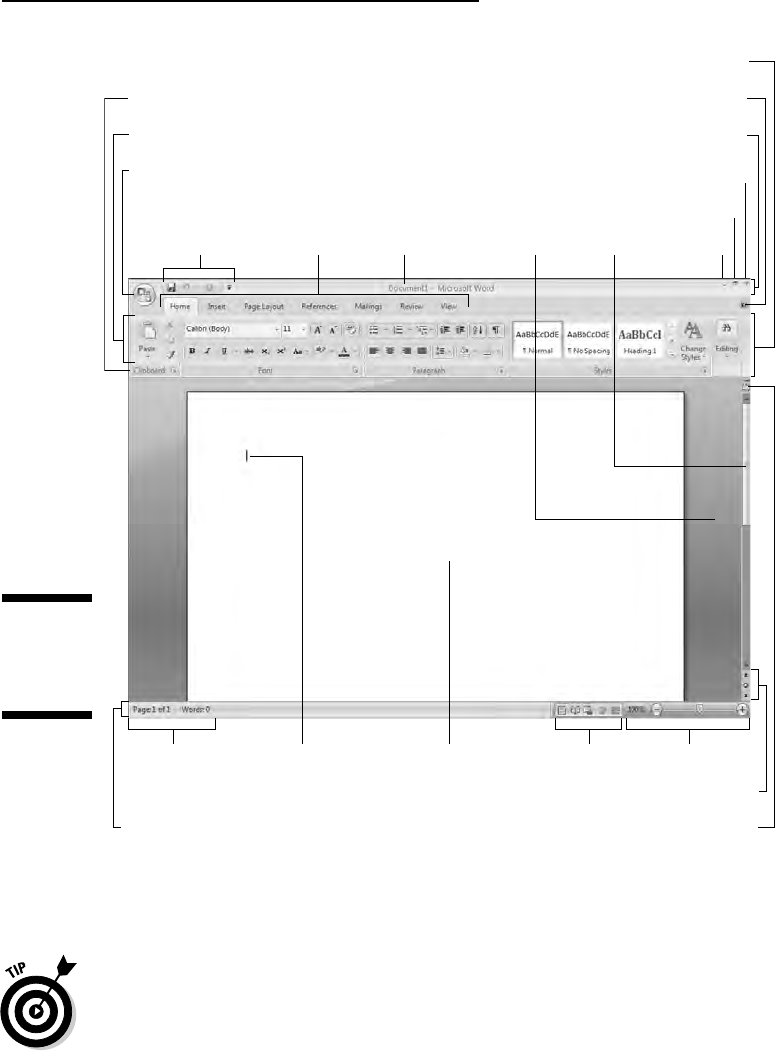

Behold Word! ..................................................................................................16

Maximize Word’s window size ............................................................16

Look! Up on the screen! .......................................................................18

The blank place where you write.......................................................19

The mouse pointer in Word ................................................................20

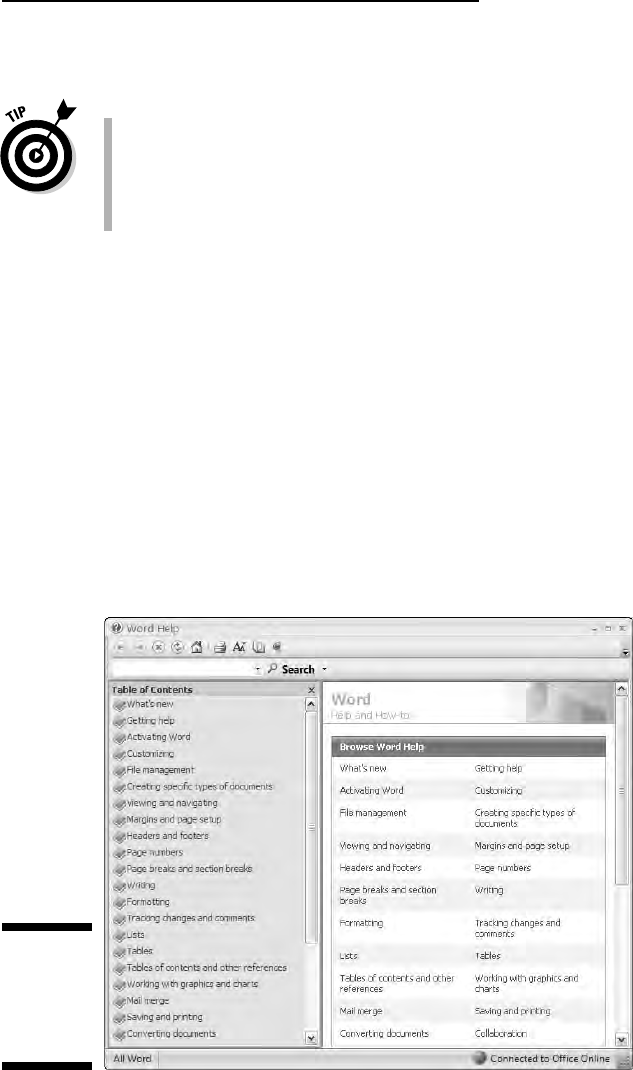

Cajoling Word to Help You ............................................................................21

When You’re All Done....................................................................................22

Quitting Word........................................................................................22

How to quit what you’re doing without quitting Word....................23

Putting Word away for a spell.............................................................24

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page ix

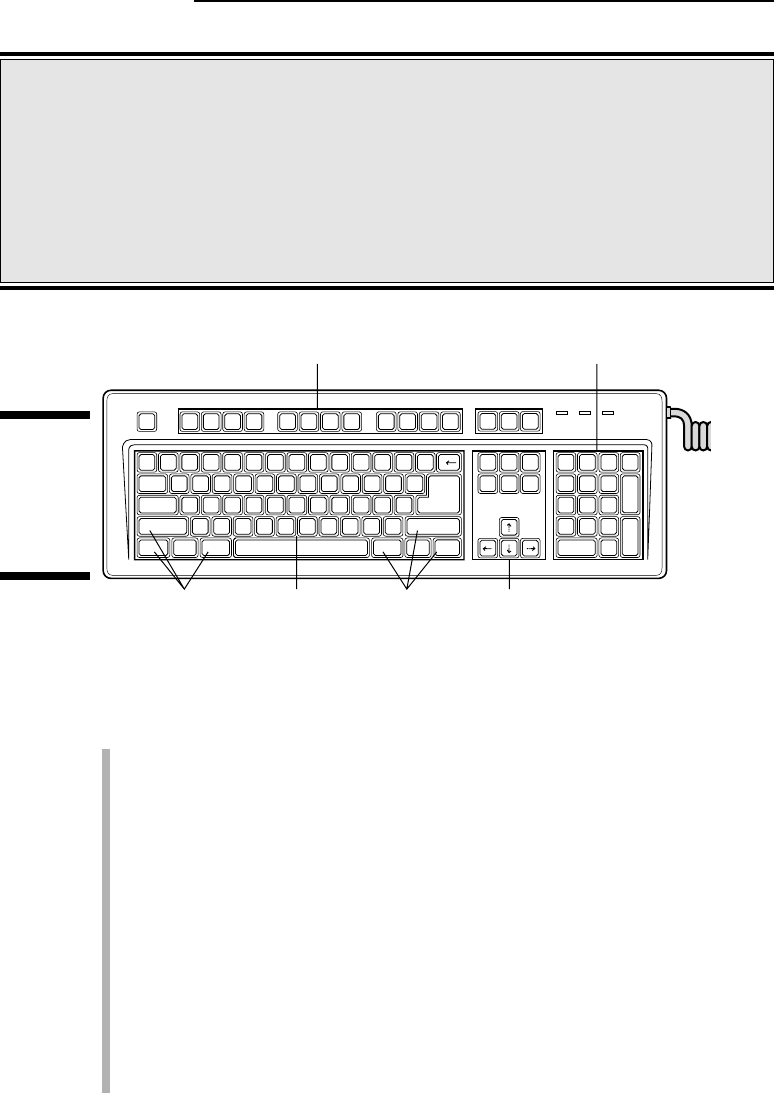

Chapter 2: Making Friends with the Keyboard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Behold the PC Keyboard! ..............................................................................25

Typing (Or, the Old Hunt-and-Peck) ............................................................27

Follow the blinking cursor ..................................................................28

When to press that Enter key .............................................................28

When to whack the spacebar .............................................................29

Backing-up and erasing keys...............................................................30

Mind your 1’s and 0’s and L’s and O’s ................................................30

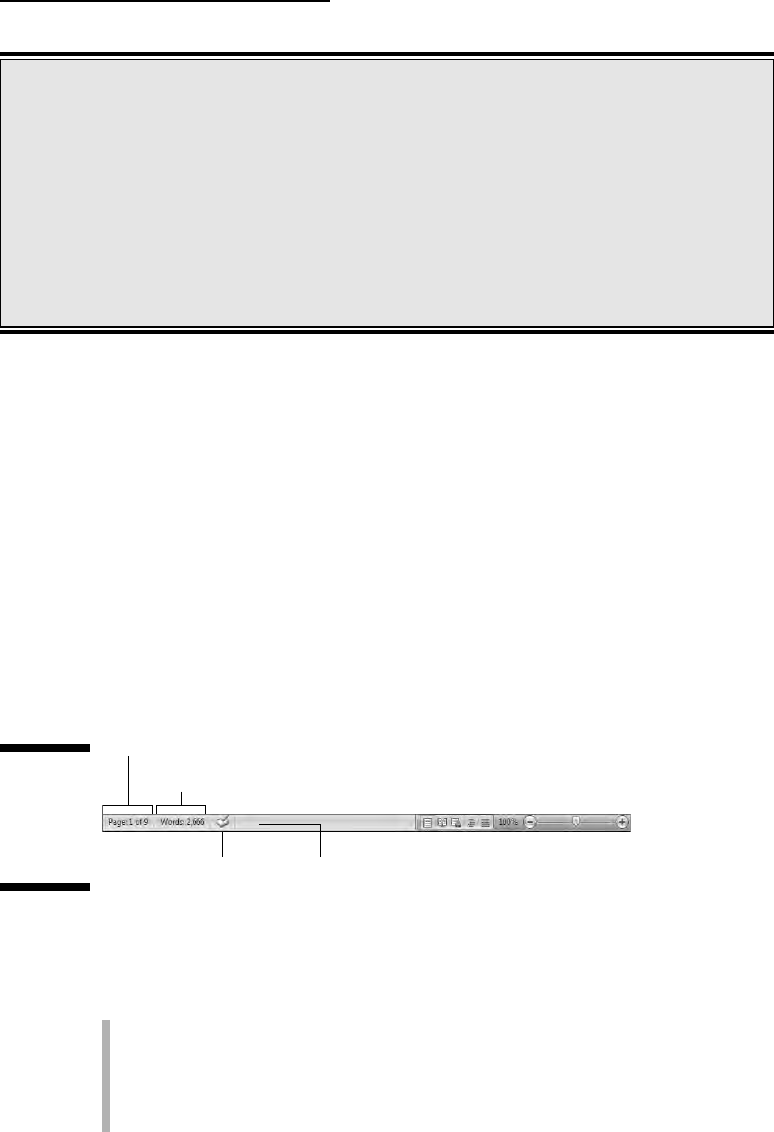

Things to Notice Whilst You Type ...............................................................31

The left end of the status bar..............................................................31

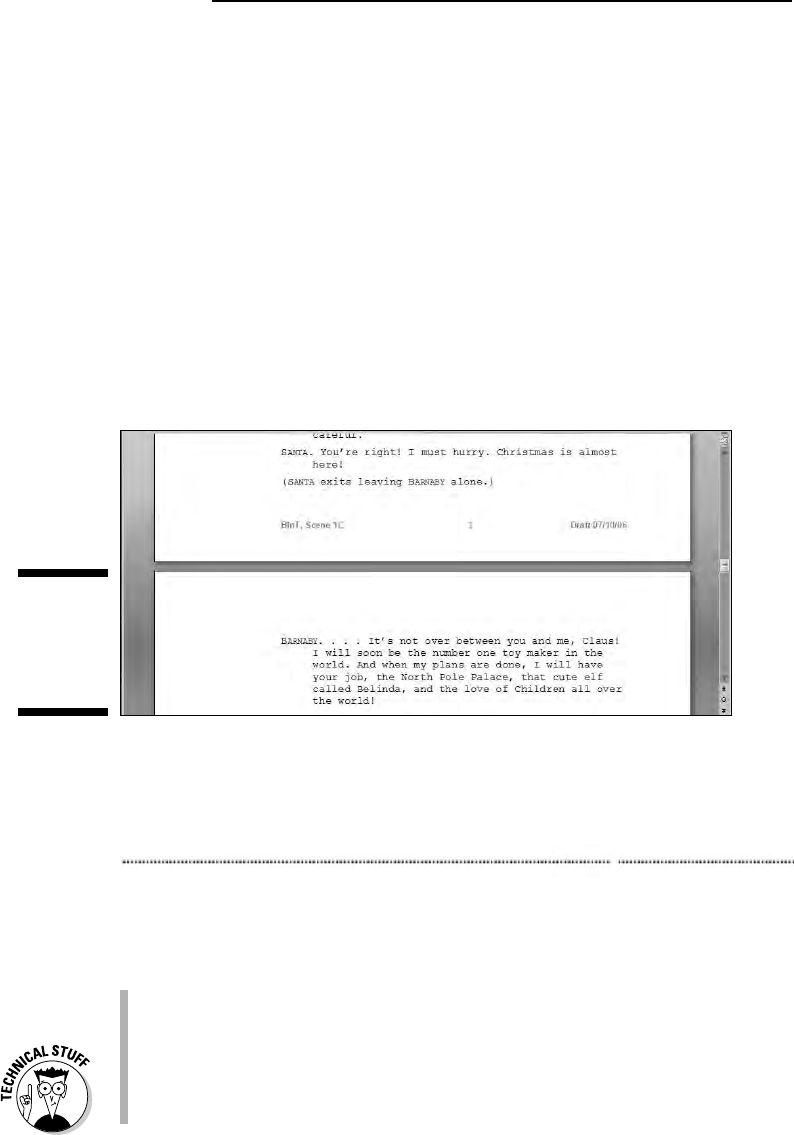

Life between pages...............................................................................32

Spots and clutter in your text.............................................................33

Strange underlines and colored text..................................................33

Word can type that for you .................................................................34

Chapter 3: A Quick Guide to Word (For the Impatient) . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

The Overview .................................................................................................36

Starting Out with a New Document .............................................................37

Typing the Text...............................................................................................38

Formatting a Document.................................................................................38

Save Your Stuff!...............................................................................................39

Finishing a Document ....................................................................................41

Proofing your work...............................................................................42

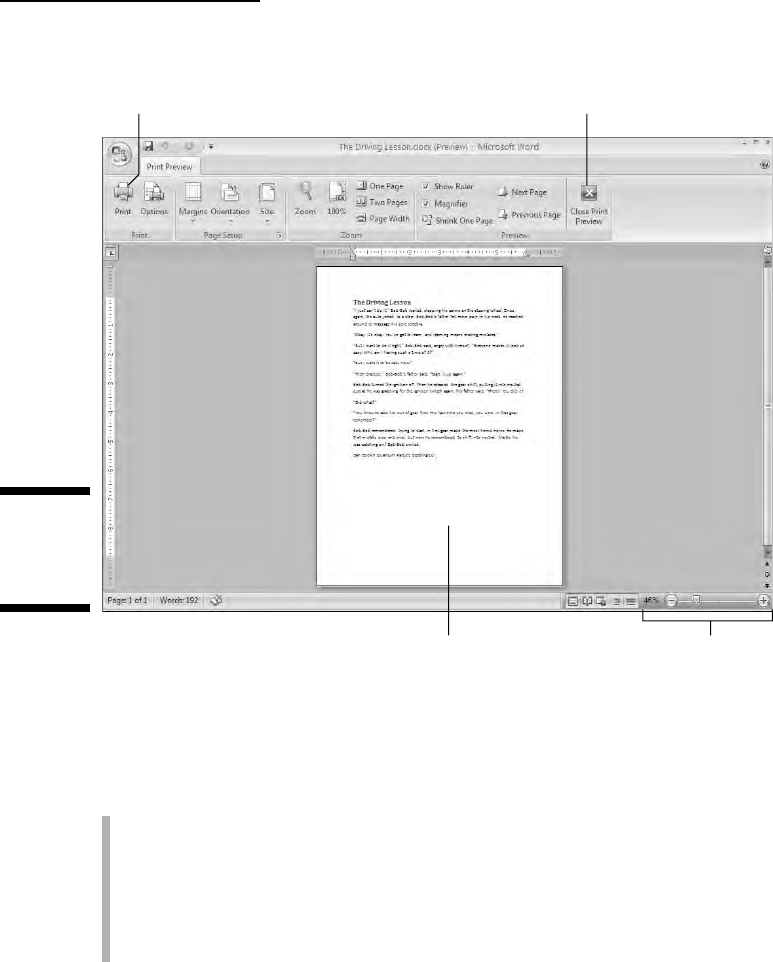

Previewing a document .......................................................................42

Printing a document.............................................................................42

Wrapping Things Up ......................................................................................44

Part II: Word Processing Basics....................................45

Chapter 4: Moving Around a Document Hither, Thither, and Yon . . . .47

Scrolling a Document.....................................................................................47

The vertical scroll bar .........................................................................47

One paragraph on the horizontal scroll bar.....................................49

Mouse scrolling tricks..........................................................................49

Moving the Insertion Pointer........................................................................50

Commanding the insertion pointer with the mouse........................50

Moving in small increments (basic arrow keys)...............................50

Moving from beginning to end............................................................51

The peculiar cases of PgUp and PgDn ...............................................51

Using Browse Buttons to Navigate...............................................................52

Getting Lost and Going Back ........................................................................53

Go to Wherever with the Go To Command.................................................53

Word 2007 For Dummies

x

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page x

Chapter 5: Editing Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55

Deleting Stuff...................................................................................................55

The delete keys: Backspace and Delete ............................................56

Deleting single characters...................................................................56

Deleting a word.....................................................................................57

Deleting more than a word..................................................................57

Splitting and Joining ......................................................................................59

Making two paragraphs from one ......................................................59

Making one paragraph from two ........................................................60

Splitting lines with a soft return.........................................................60

Mistakes? Mistakes? Undo Them with Haste .............................................60

Now mark me, how I will undo myself...............................................61

Redo, the Undo-Undo command ........................................................61

Redo, the Repeat Typing command...................................................62

Chapter 6: Find and Replace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

Text Happily Found........................................................................................65

O villainous text tidbit! Seek it out! ....................................................66

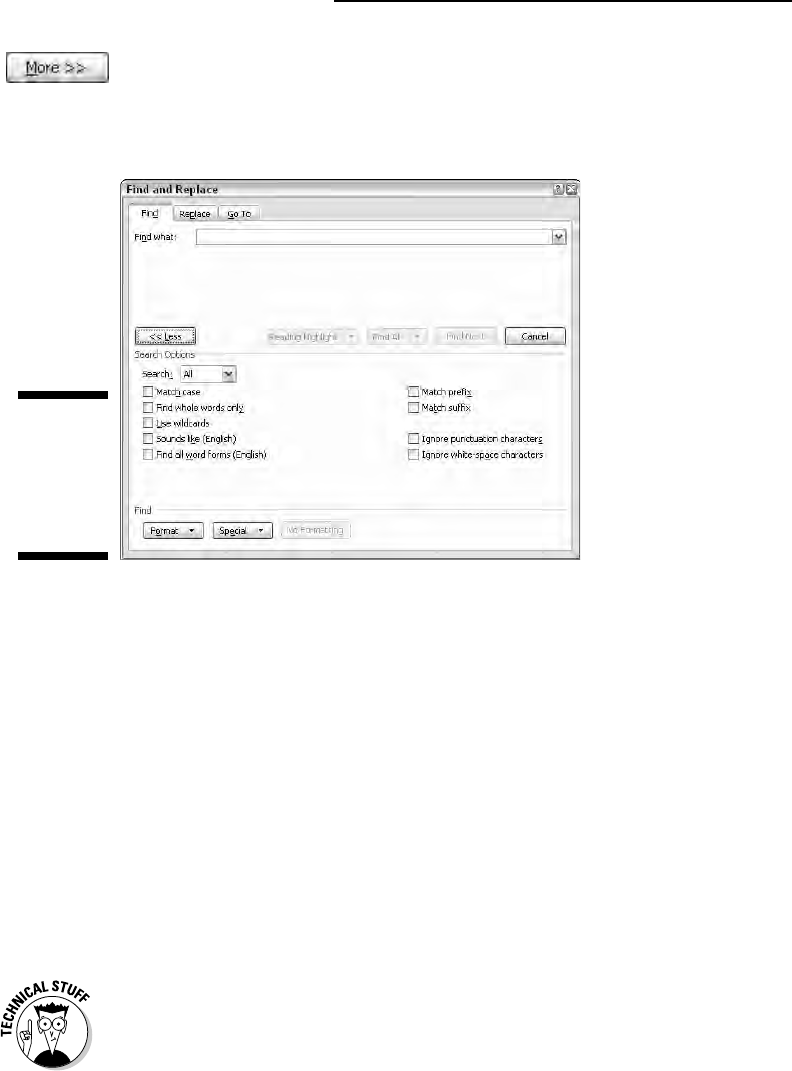

The Super Find command ...................................................................67

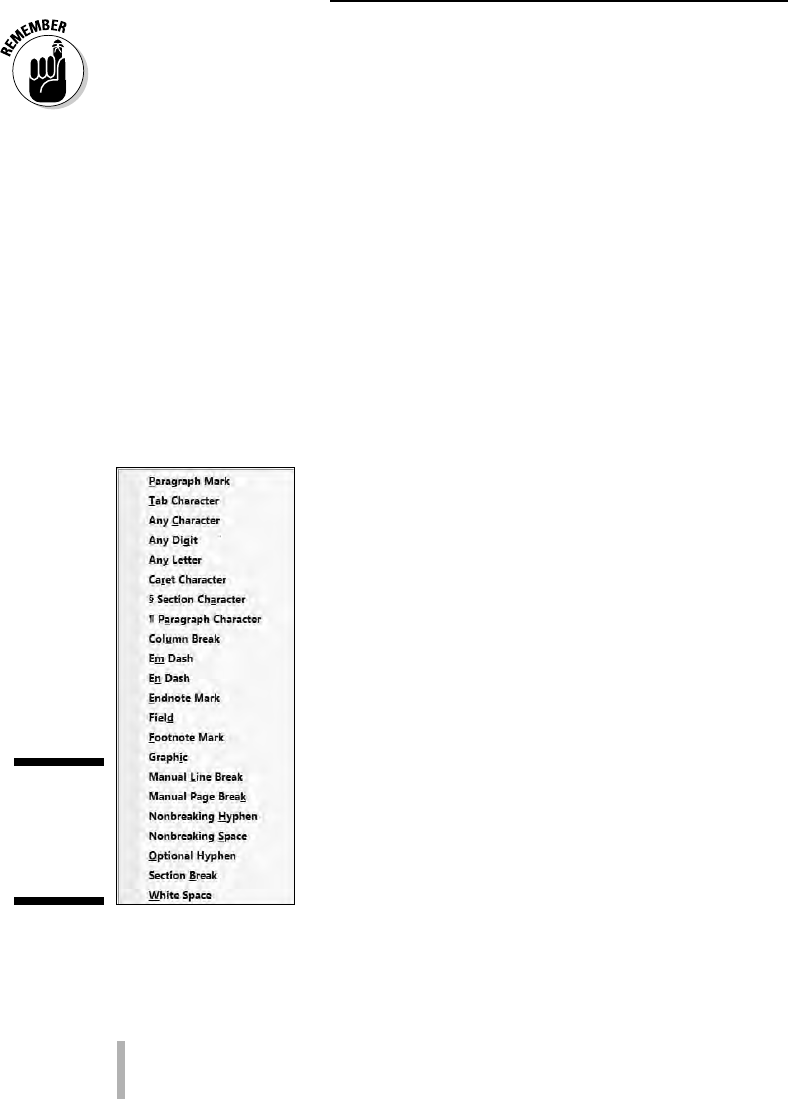

Finding stuff you can’t type in ............................................................70

Finding formatting................................................................................72

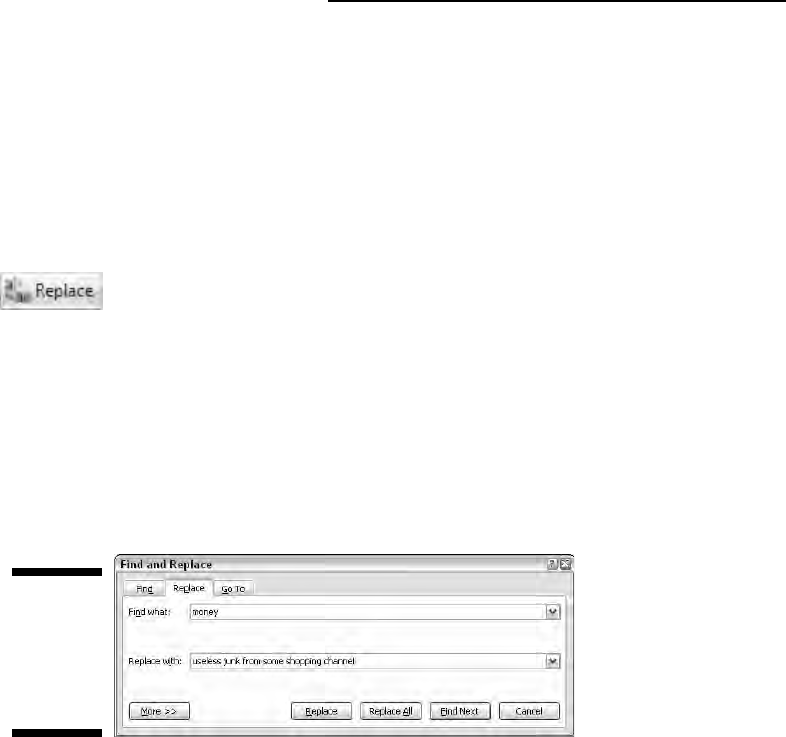

Replacing What’s Been Found ......................................................................74

The miracle of the Replace All button...............................................76

Finding and replacing formatting.......................................................76

Chapter 7: Text Blocks, Stumbling Blocks, Writer’s Blocks . . . . . . . .79

What Is a Block of Text? ................................................................................80

Marking a Chunk of Text As a Block ............................................................81

Using the keyboard to select text.......................................................81

Marking a block with the mouse ........................................................82

Using the F8 key to mark a block .......................................................84

Blocking the whole dang-doodle document .....................................85

Deselecting a Block........................................................................................86

You’ve Marked the Block — Now What?.....................................................86

Copying a block ....................................................................................87

Moving a block......................................................................................88

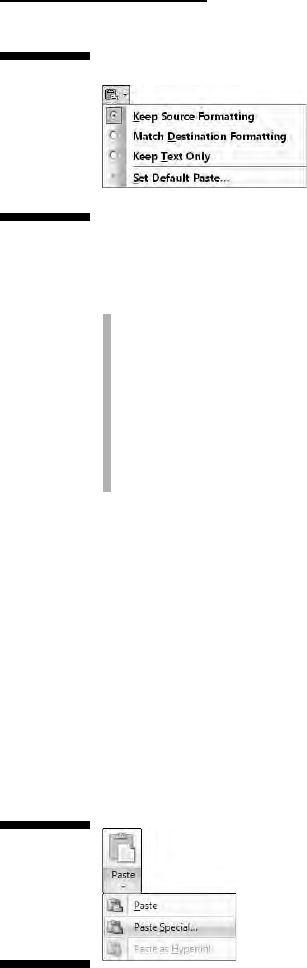

Options for pasting text.......................................................................88

Special pasting......................................................................................89

Copying or moving a block with the mouse .....................................90

Copying and moving with the F2 key.................................................91

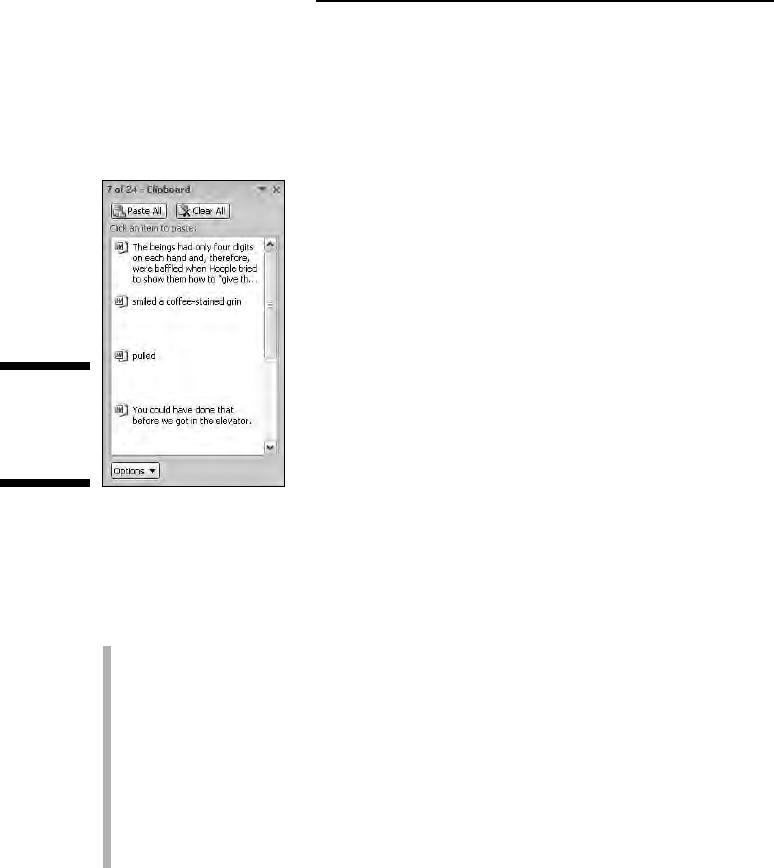

The Miracle of Collect-and-Paste .................................................................91

Looking at the Clipboard.....................................................................91

Pasting from the Clipboard task pane ...............................................92

Cleansing the Clipboard task pane.....................................................93

xi

Table of Contents

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xi

Chapter 8: Proofing Your Document (Spelling and Grammar) . . . . . . .95

Hun Dewing Yore Mist Aches........................................................................96

Check Your Spelling .......................................................................................96

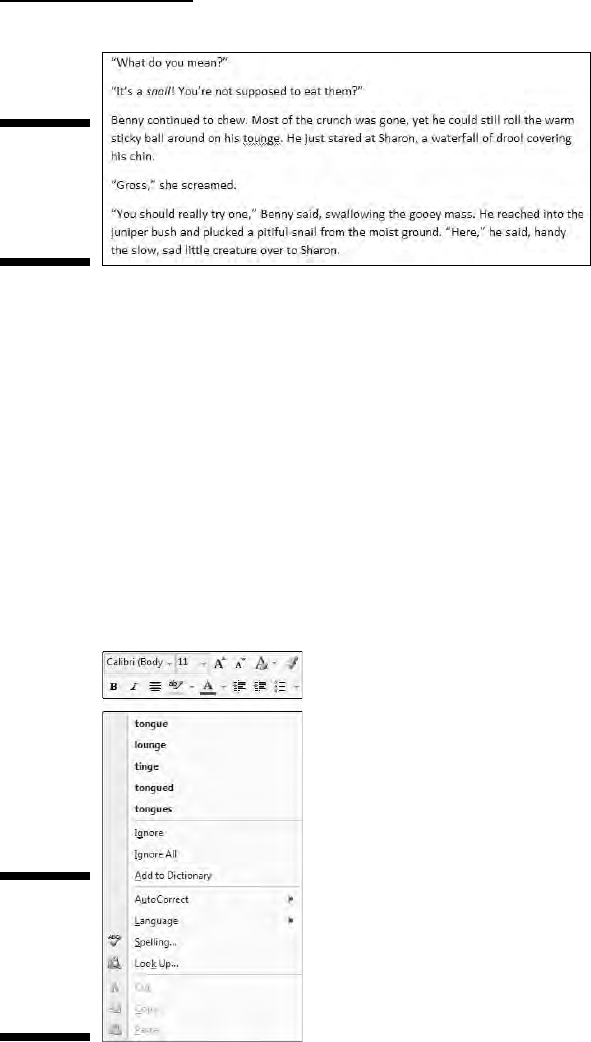

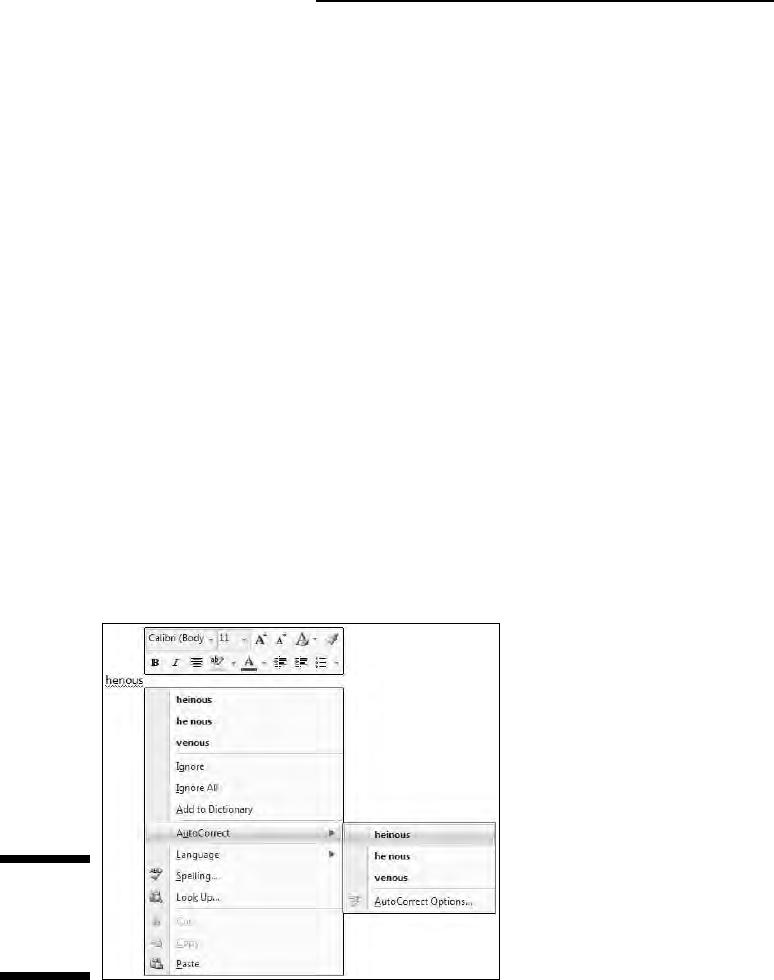

The red zigzag of shame......................................................................96

What to do when the spell checker stupidly assumes

that a word is misspelled but in fact it isn’t..................................98

Undoing an Ignore All command........................................................99

Un-adding words to the dictionary ..................................................100

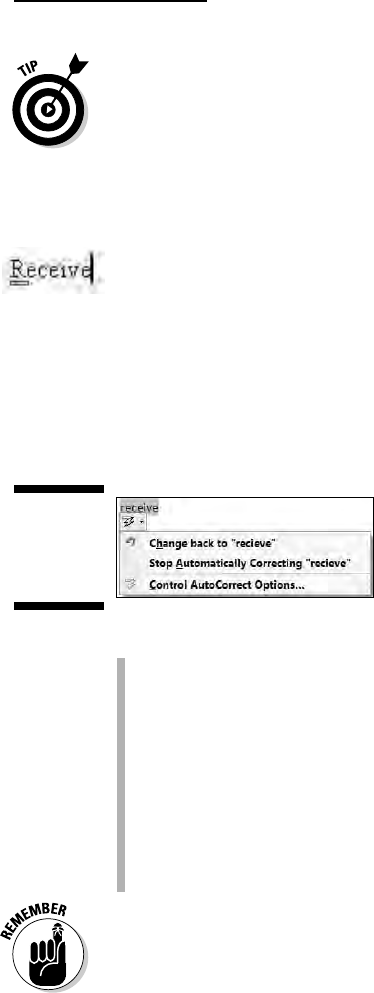

Instant Text-Fixin’ with AutoCorrect .........................................................101

AutoCorrect in action ........................................................................101

Do your own AutoCorrect entries....................................................102

Undoing an AutoCorrect correction ................................................103

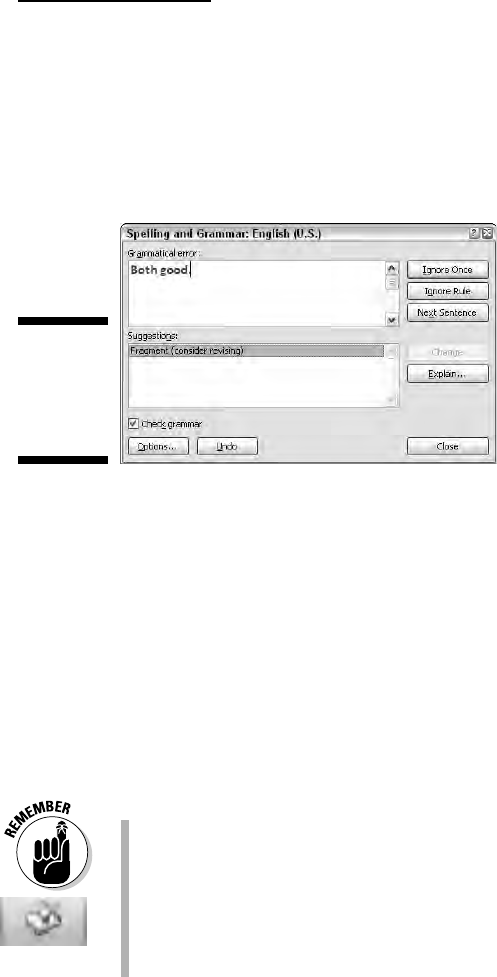

Grammar Be Good........................................................................................104

Proofing Your Entire Document at Once...................................................104

Customizing Proofing Options....................................................................106

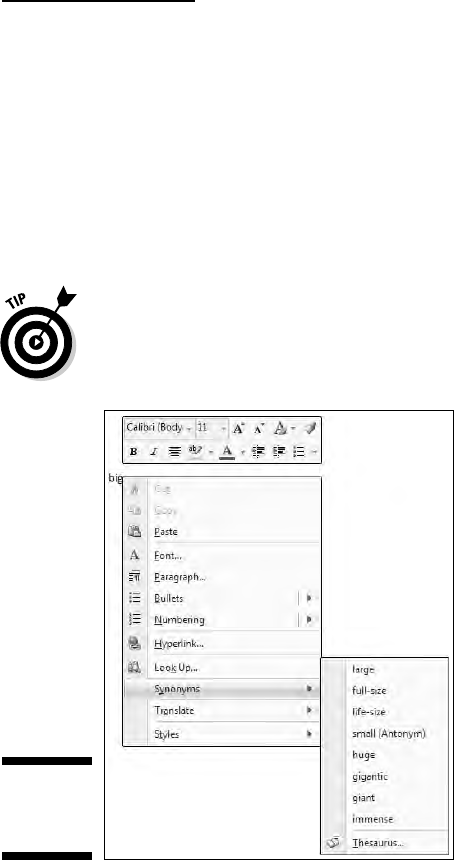

Improving Your Word Power.......................................................................106

A thesaurus is not a colossal prehistoric beast .............................107

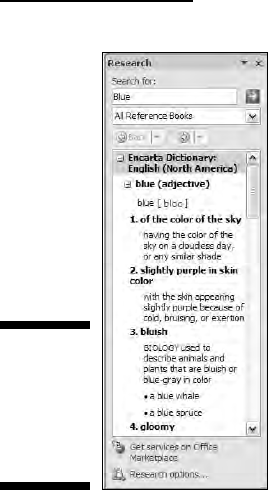

The Research task pane.....................................................................108

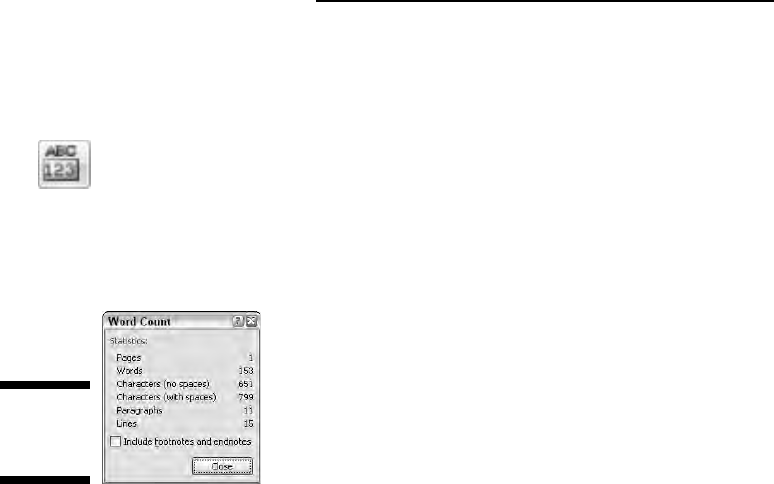

Making Every Word Count ..........................................................................109

Chapter 9: Documents and Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

All About Files...............................................................................................111

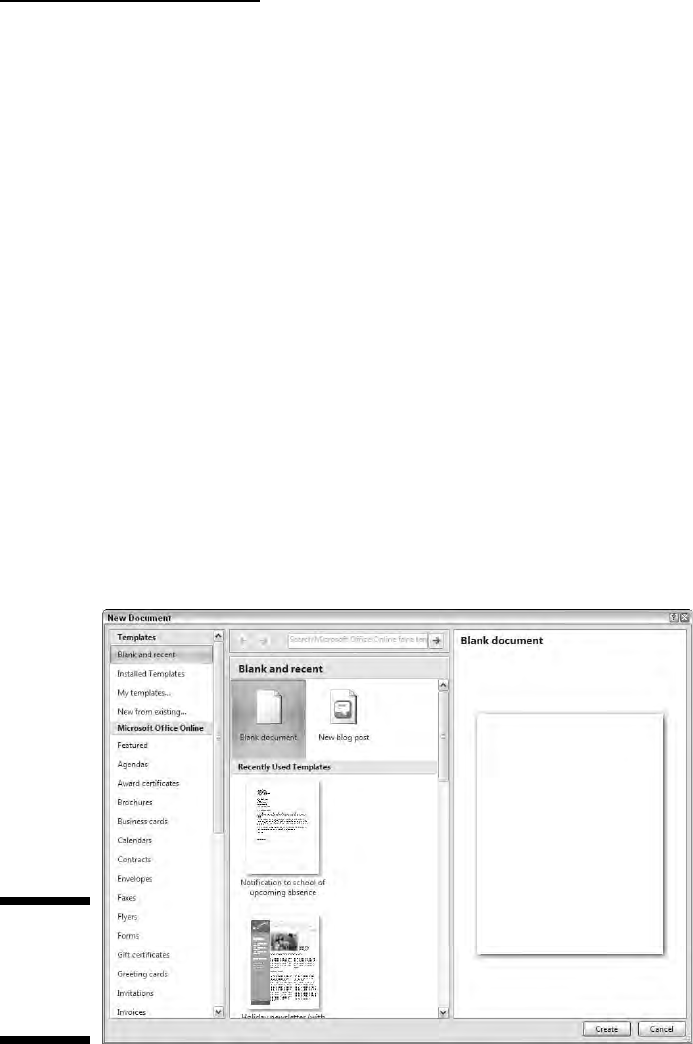

Making a New Document.............................................................................112

Quick! A blank sheet of paper!..........................................................113

Using a template.................................................................................114

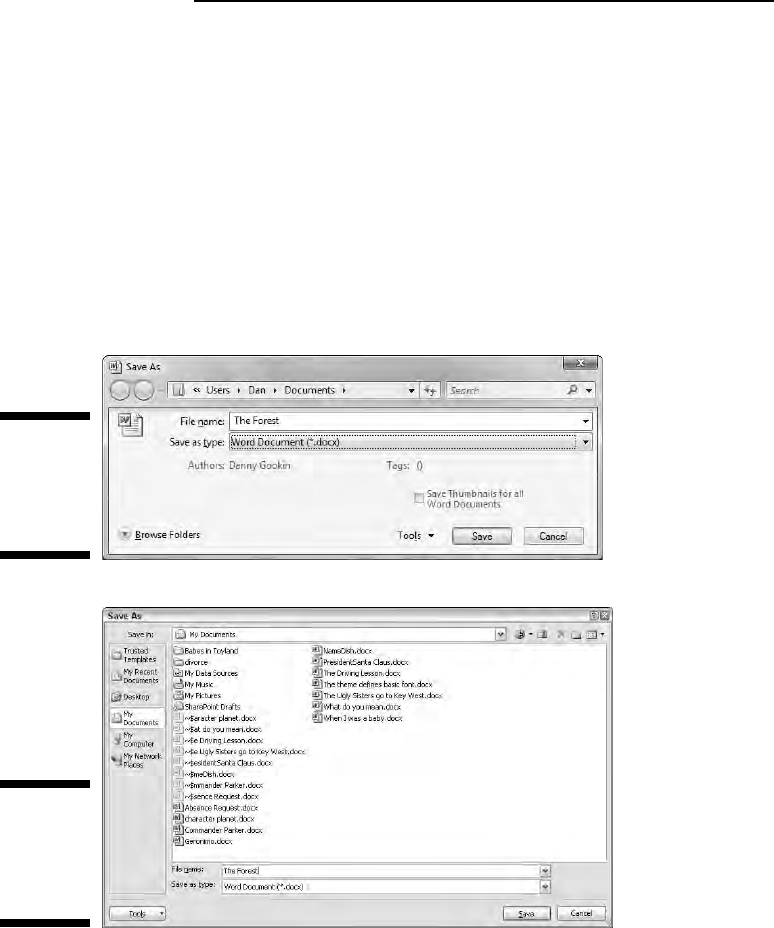

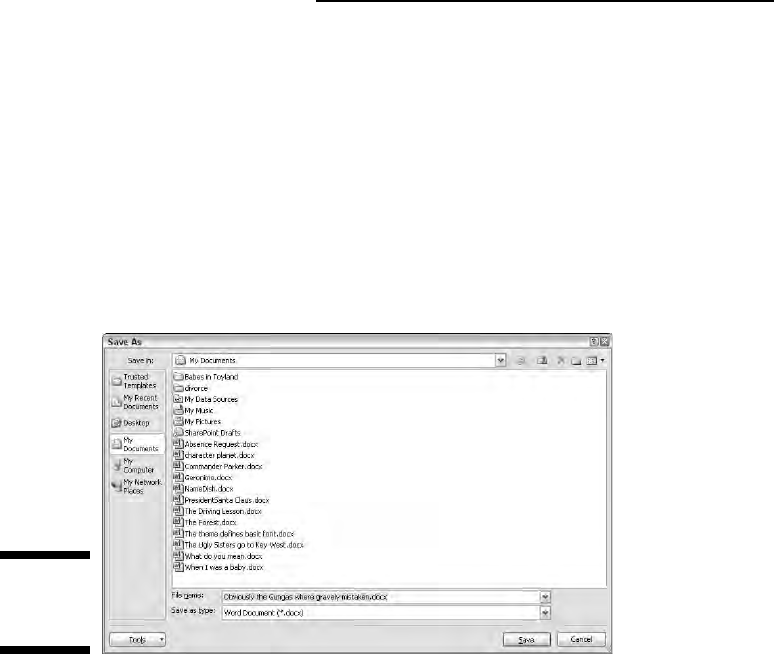

Saving a Document.......................................................................................115

Saving a new document to disk the first time.................................115

Problems with saving a document to disk......................................117

Saving or updating a document........................................................118

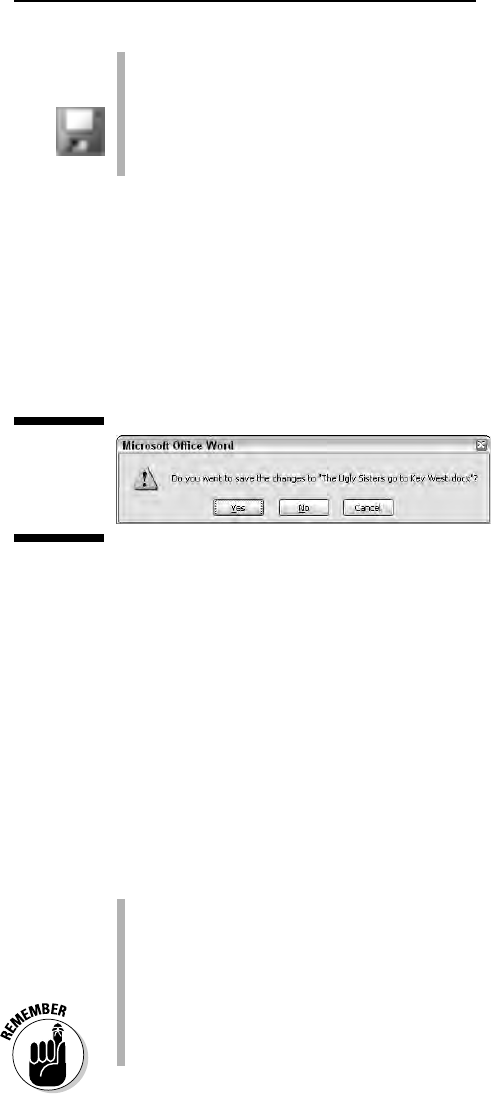

Saving when you’re done...................................................................119

Not saving a document......................................................................120

Opening a Document ...................................................................................120

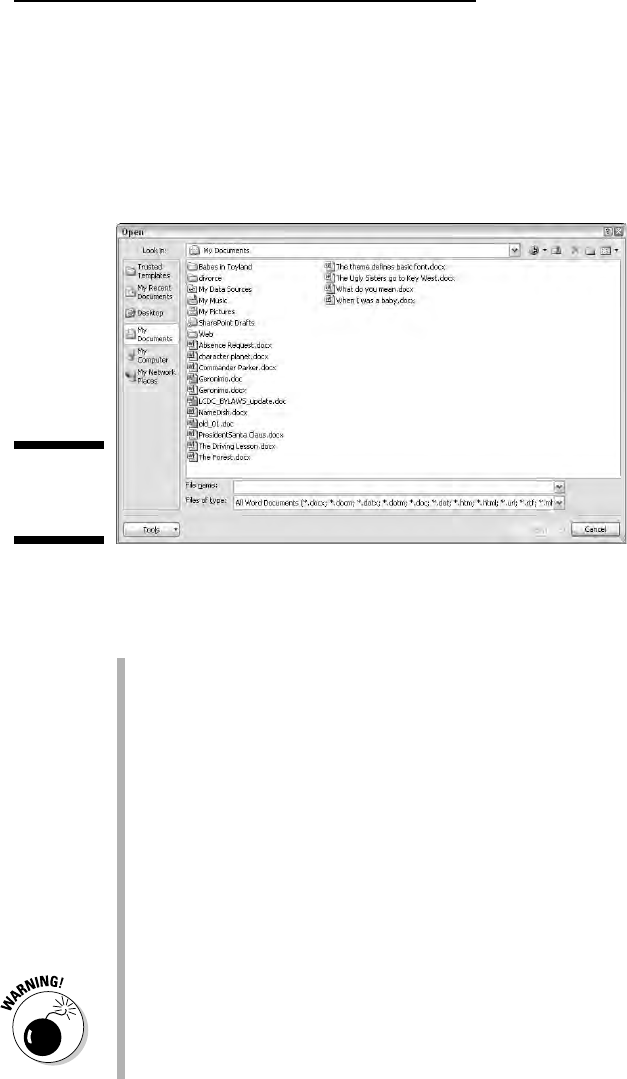

Using the traditional Open command..............................................120

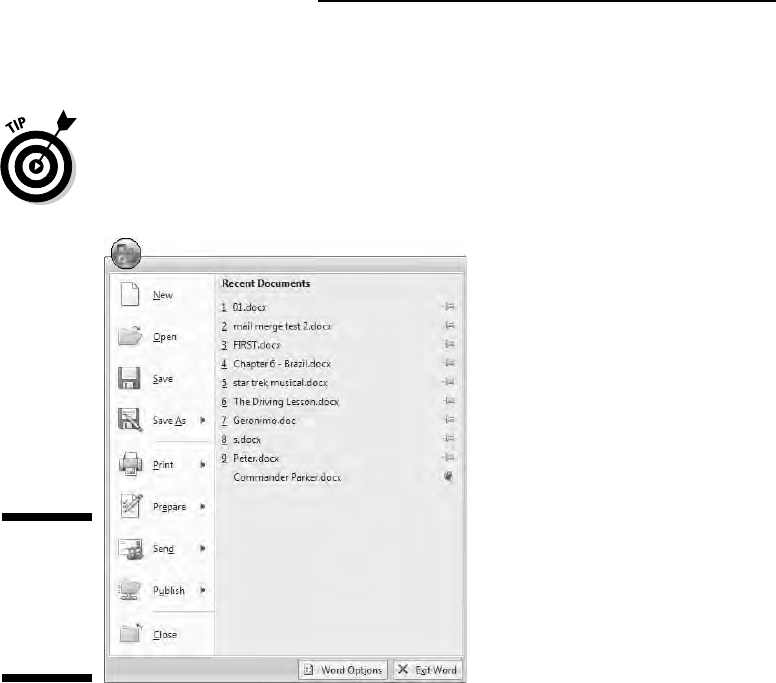

A handy way to open a recent file....................................................122

Opening one document inside another...........................................122

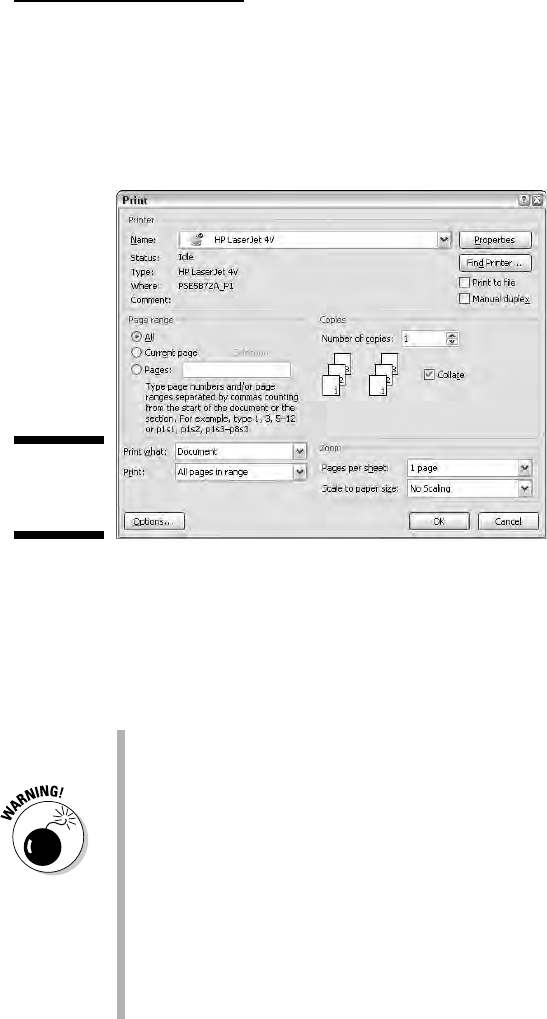

Chapter 10: The Printer, the Paper, the Document Maker . . . . . . . . .125

Preparing the Printer...................................................................................125

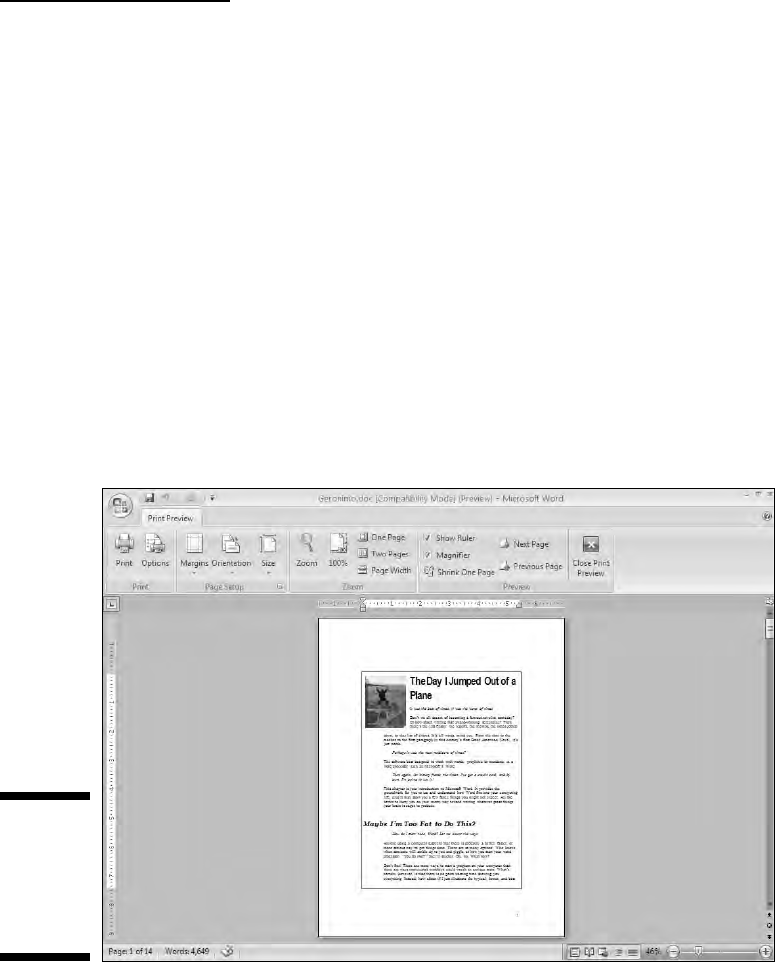

Preview Before You Print ............................................................................126

Printing a Whole Document........................................................................128

Printing backward ..............................................................................130

Printing a document quickly.............................................................131

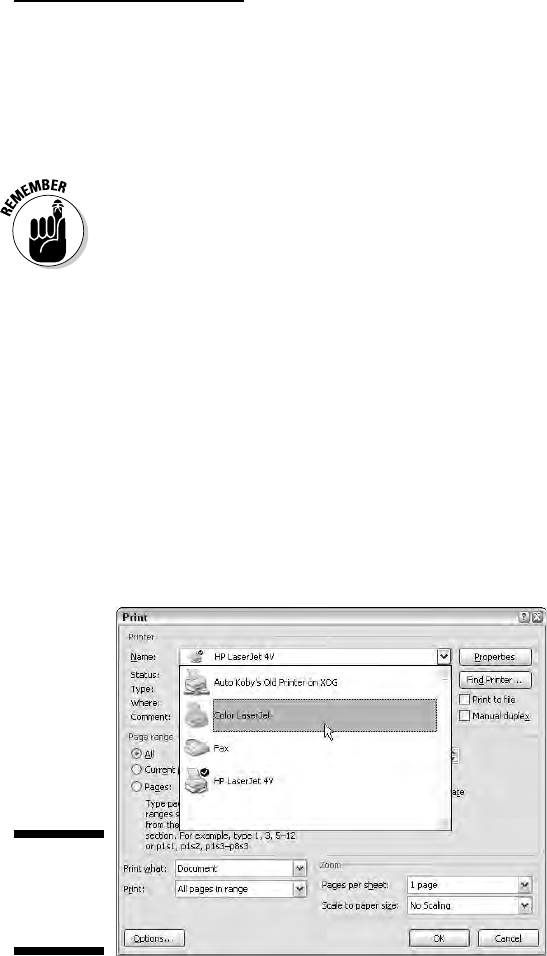

Choosing another printer..................................................................131

Word 2007 For Dummies

xii

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xii

Printing Part of a Document .......................................................................132

Printing a specific page .....................................................................132

Printing a range of pages...................................................................133

Printing a block...................................................................................134

Printing More than One Copy of Something.............................................134

Canceling a Print Job (Omigosh!)...............................................................135

Part III: Formatting...................................................137

Chapter 11: Formatting Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .139

How to Format Text .....................................................................................139

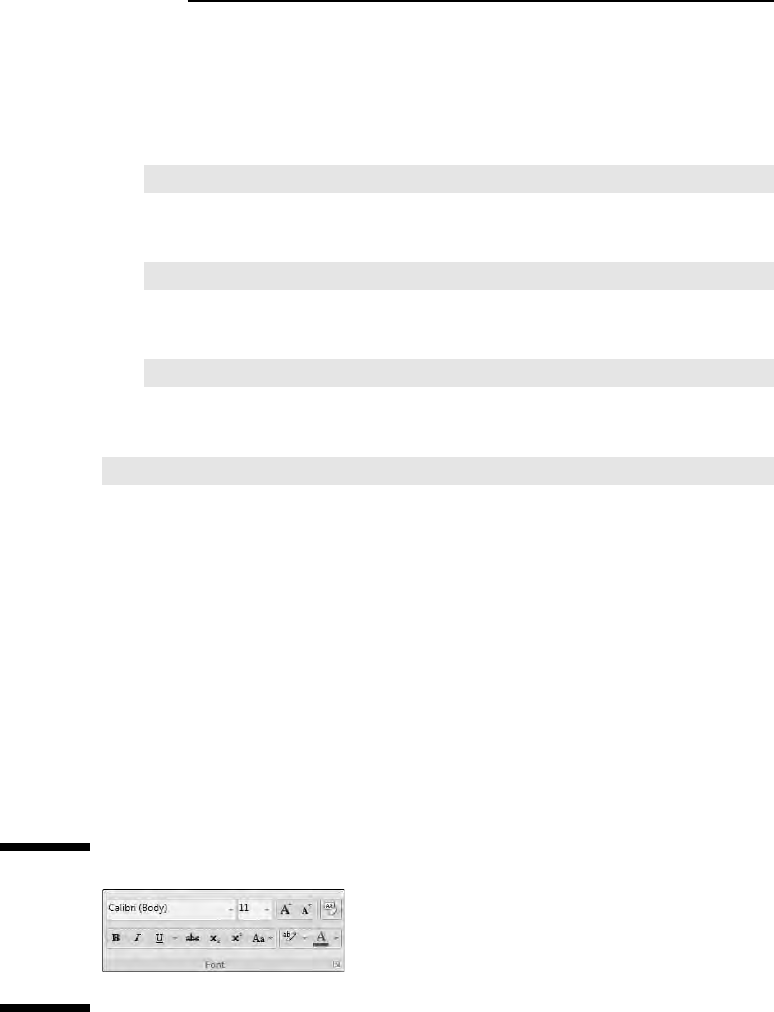

Basic Text Formatting..................................................................................140

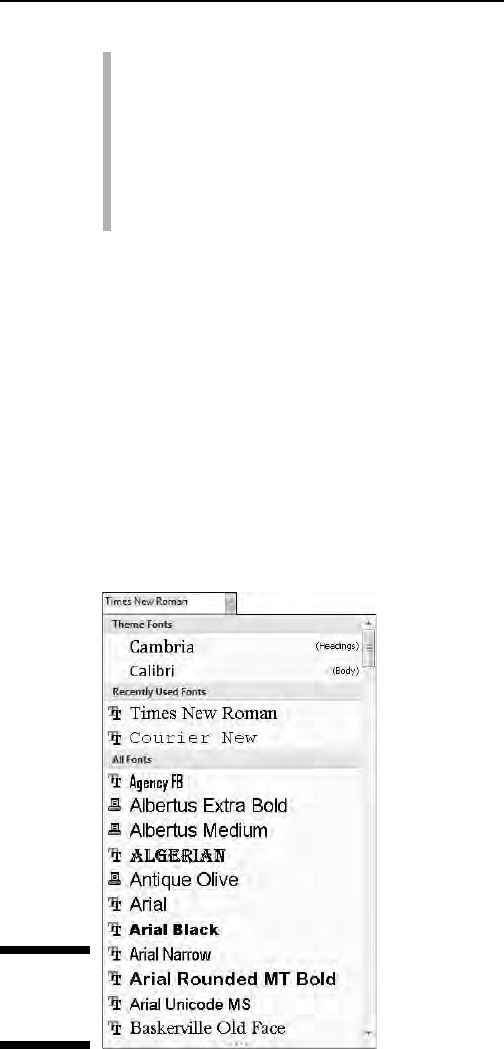

Changing the font ...............................................................................141

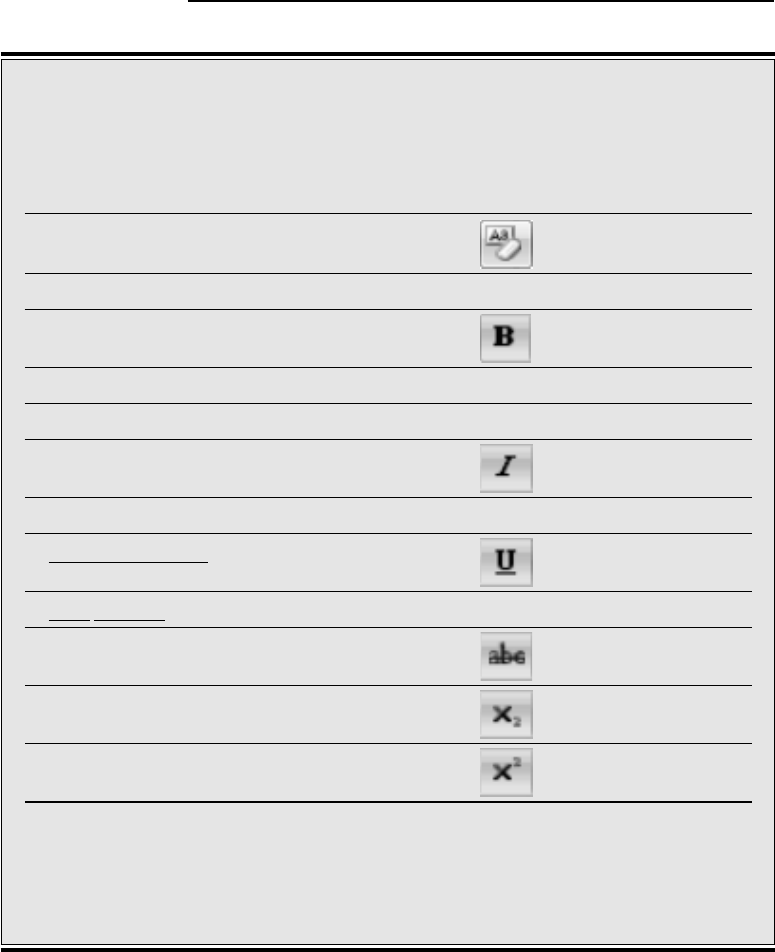

Character formats (bold, italic, and so on).....................................142

Text Transcending Teeny to Titanic ..........................................................144

Setting the text size............................................................................145

Nudging text size ................................................................................145

More Colorful Text Makes Not for More Colorful Writing.......................146

Undoing All This Text-Formatting Nonsense............................................147

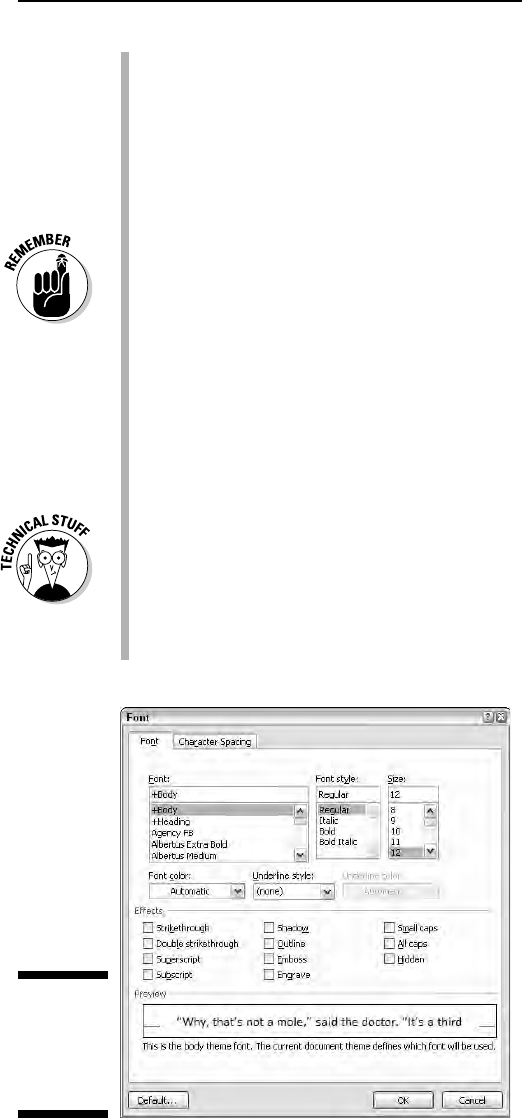

Fun and Formatting in the Font Dialog Box ..............................................148

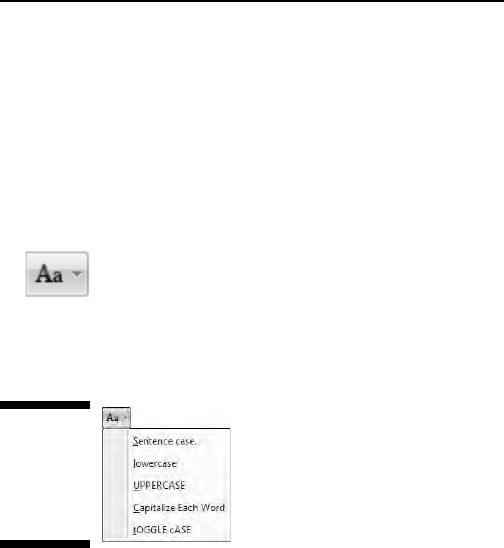

Changing the CASE of Text..........................................................................151

Chapter 12: Formatting Paragraphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .153

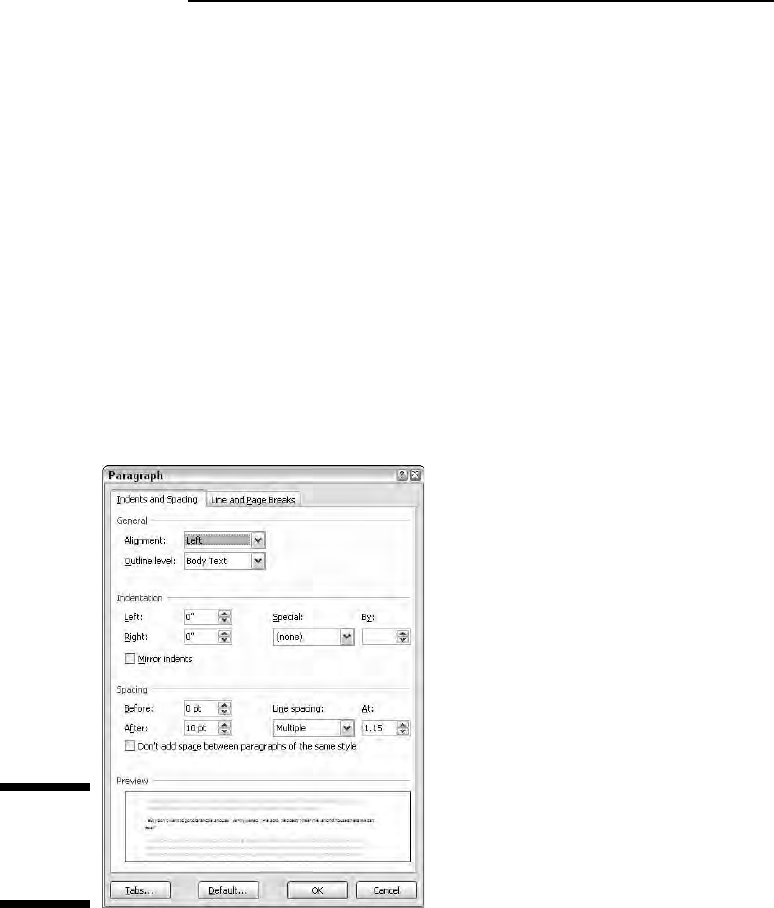

How to Format a Paragraph........................................................................153

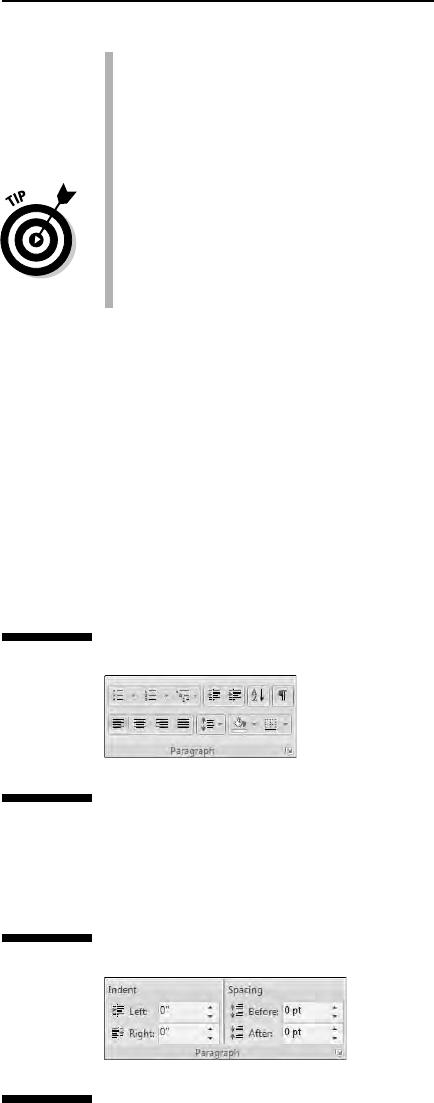

Where the Paragraph Formatting Commands Lurk.................................155

Paragraph Justification and Alignment .....................................................156

Line up on the left!..............................................................................157

Everyone center!.................................................................................157

Line up on the right!...........................................................................157

Full justification! (Full justification — aye, sir!)..............................158

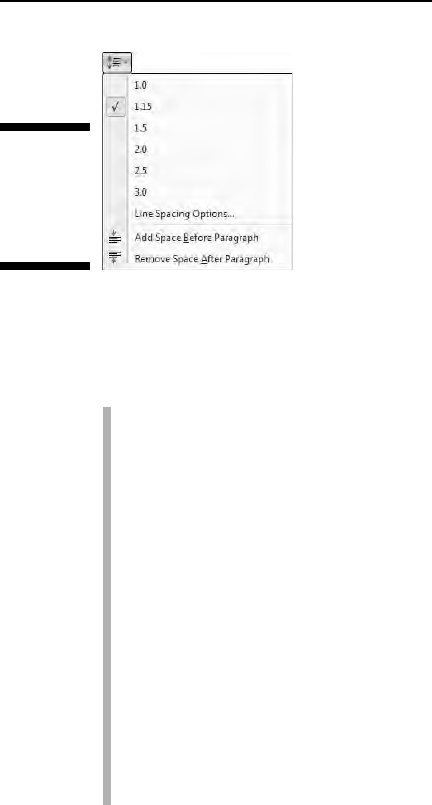

Making Room Before, After, or Inside Your Paragraphs..........................158

Traditional line spacing.....................................................................158

More line spacing options.................................................................159

That space between paragraphs......................................................160

Paragraph Indentation.................................................................................161

Indenting the first line of a paragraph.............................................161

Making a hanging indent ...................................................................162

Indenting a whole paragraph............................................................163

Setting the paragraph margins .........................................................163

Who Died and Made This Thing Ruler?.....................................................164

xiii

Table of Contents

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xiii

Chapter 13: Setting Tabs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .167

The Story of Tab...........................................................................................167

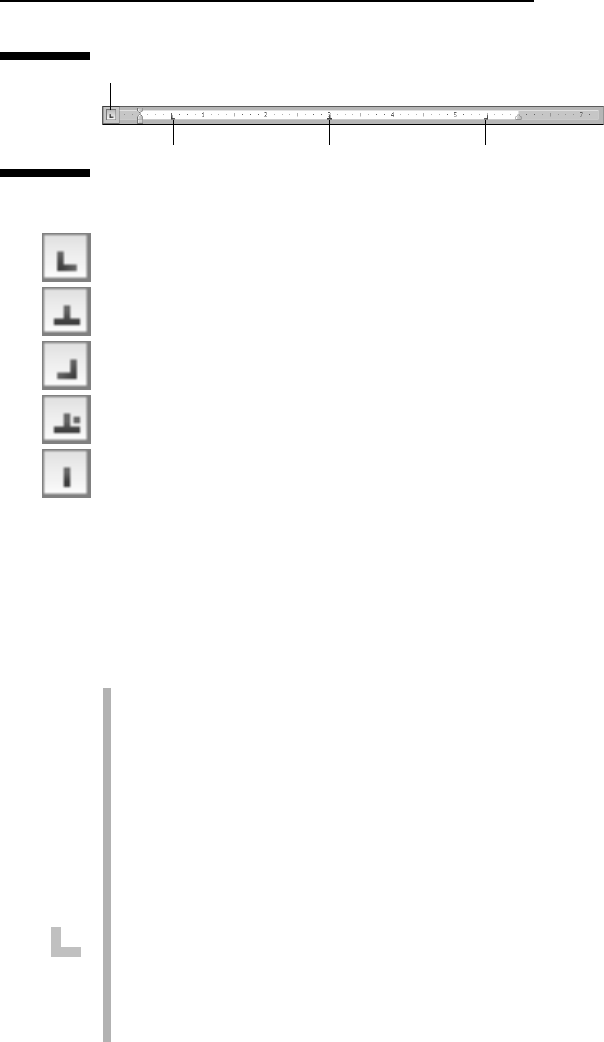

The Tab Stops Here......................................................................................168

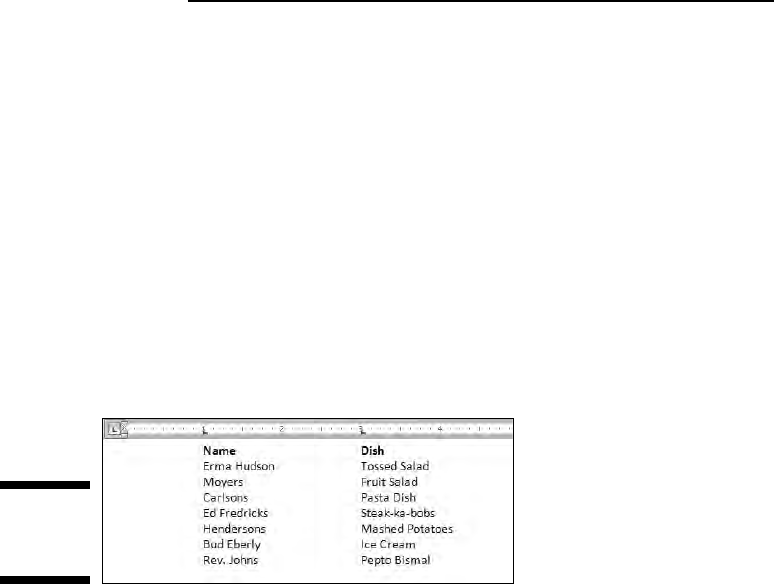

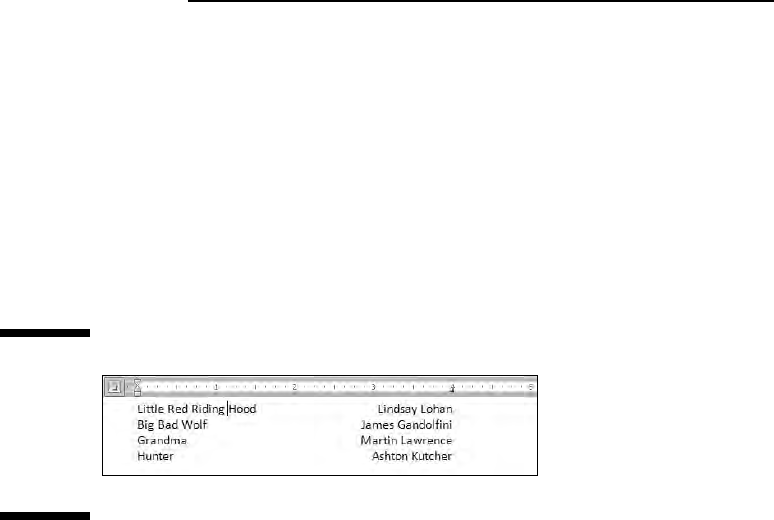

The Standard Left Tab Stop ........................................................................170

The tabbed list....................................................................................170

The tab-tab-paragraph thing.............................................................172

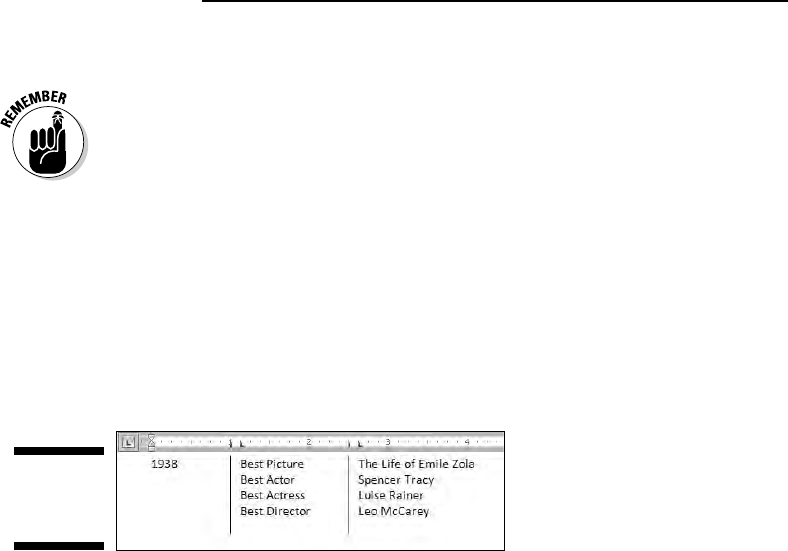

The Center Tab Stop....................................................................................173

The Right Tab Stop.......................................................................................174

Right stop, left stop list .....................................................................175

Tab, right stop list ..............................................................................176

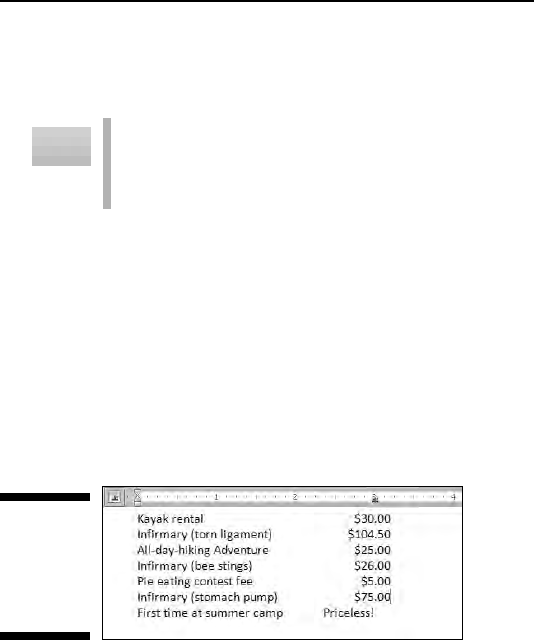

The Decimal Tab...........................................................................................177

The Bar Tab...................................................................................................178

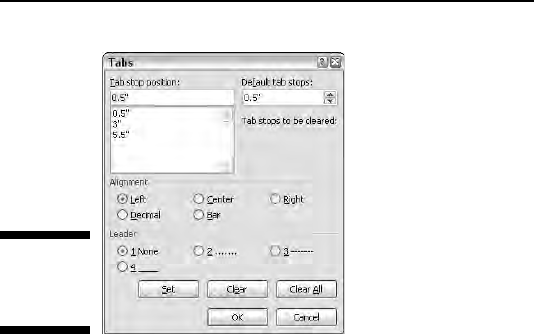

The Tabs Dialog Box ....................................................................................178

Setting a tab in the Tabs dialog box.................................................179

Setting leader tabs..............................................................................180

Default tab stops ................................................................................181

Unsetting a Tab Stop....................................................................................182

Chapter 14: Formatting Pages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .183

Describe That Sheet o’ Paper .....................................................................183

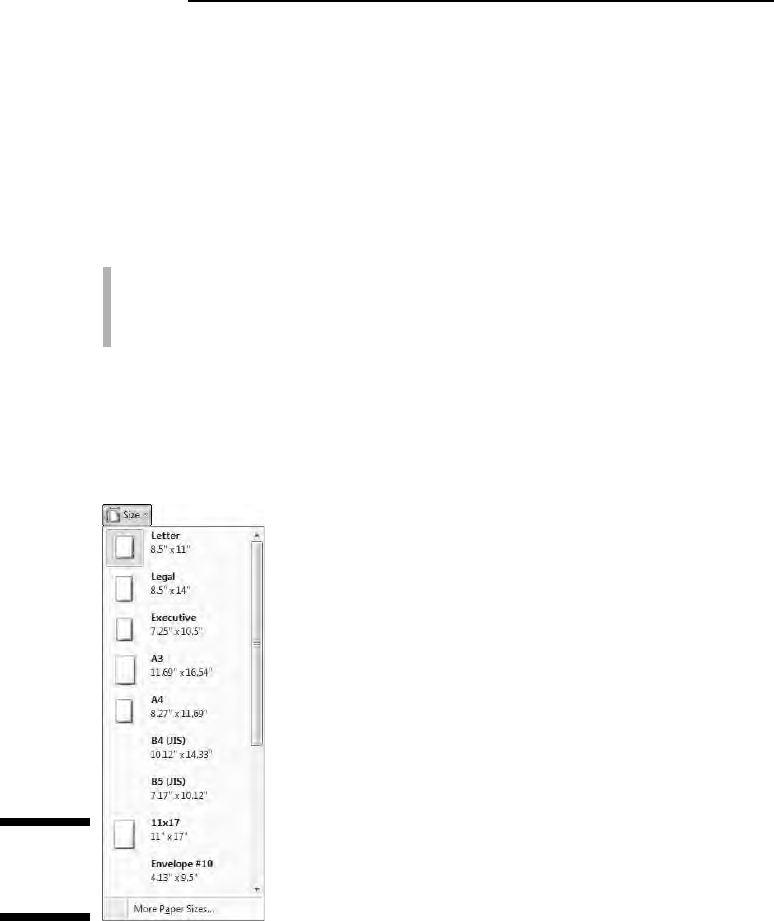

A page is a sheet of paper about “this” big.....................................184

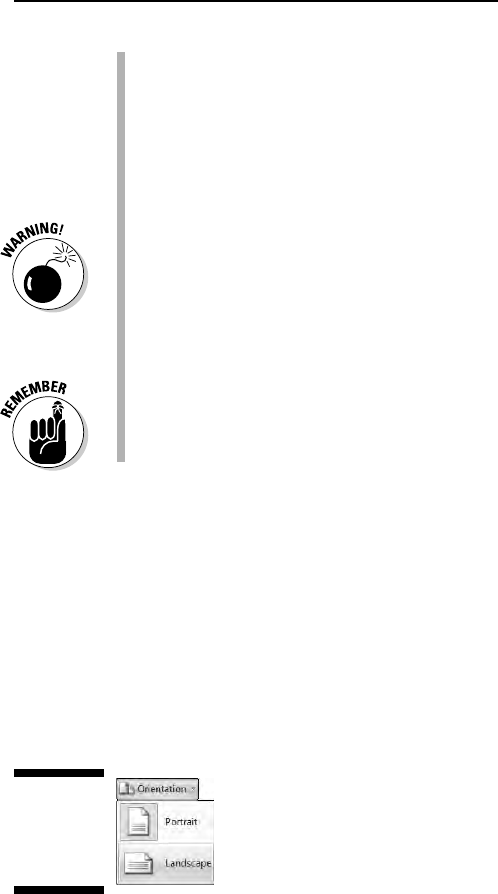

Page orientation (landscape or portrait) ........................................185

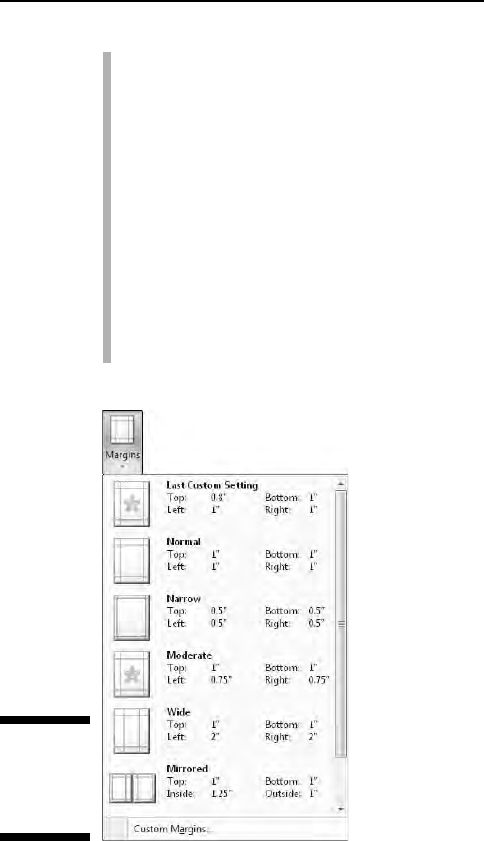

Marginal information .........................................................................186

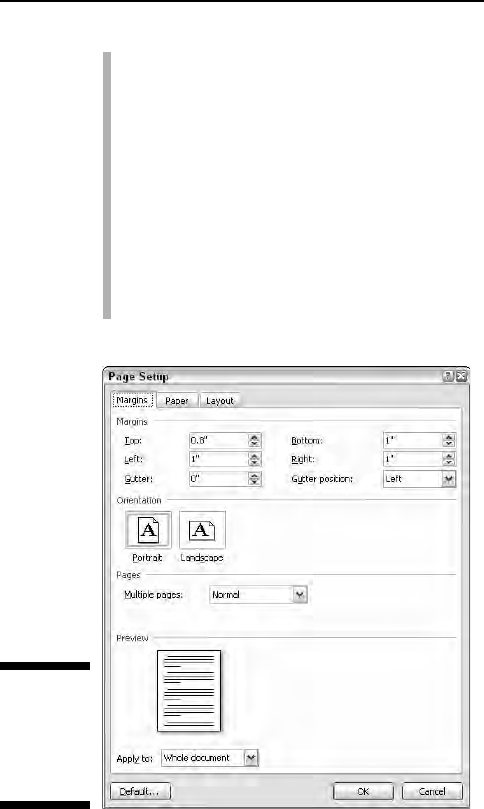

Behold the Page Setup dialog box....................................................187

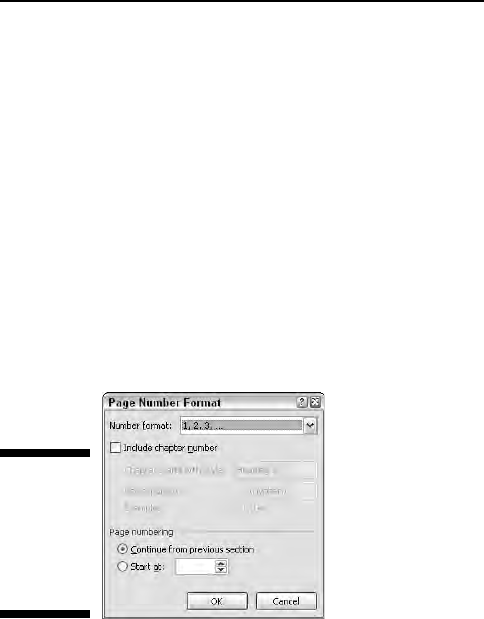

Page Numbering ...........................................................................................189

Where to stick the page number? ....................................................190

Starting off with a different page number .......................................191

Numbering with Roman numerals ...................................................192

Removing page numbers...................................................................192

New Pages from Nowhere ...........................................................................192

Starting afresh on a new, blank page ...............................................192

Inserting a whole, blank page ...........................................................193

Page Froufrou ...............................................................................................194

Color your page ..................................................................................194

The distinguished watermark...........................................................195

Chapter 15: Formatting Documents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .197

The Oft Misunderstood Yet Useful Concept of Sections.........................197

Understanding sections.....................................................................198

Creating a section...............................................................................199

Using a section....................................................................................200

Deleting a section break ....................................................................201

Adding a Cover Page (Sneaky and Quick).................................................201

Word 2007 For Dummies

xiv

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xiv

Hats and Shoes for Your Pages (Headers and Footers) ..........................202

Adding a header .................................................................................203

Editing a header..................................................................................204

Making odd and even headers..........................................................206

“But I don’t want a header on my first page!”.................................207

Headers and document sections......................................................207

Removing a header.............................................................................209

Chapter 16: The Styles of Word . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .211

The Big Style Overview ...............................................................................211

Types of styles....................................................................................212

Styles quick and custom....................................................................213

Using a style........................................................................................213

Effortless Formatting Fun with Quick Styles ............................................214

Applying a Quick Style to your text .................................................214

Employing the Styles task pane........................................................216

The Styles task pane lite....................................................................218

Discovering which style you’re using..............................................218

Switching to another style set ..........................................................219

Unapplying a style..............................................................................219

Do-It-Yourself Styles.....................................................................................220

Creating a style based on text you’ve already formatted .............220

Creating character, list, and other types of styles .........................223

Modifying a style ................................................................................223

Giving your style a shortcut key ......................................................224

Deleting a style ...................................................................................225

Managing All Your Various Styles...............................................................225

Chapter 17: Themes and Templates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .227

Formatting Fast and Fancy with a Theme.................................................227

Applying a document theme.............................................................228

Modifying or creating a theme..........................................................229

Whipping Out Similar Documents Based on a Template ........................230

What is a template?............................................................................231

Creating a template based on a document you already have ......231

Making a new template from scratch...............................................234

Modifying a template you created ...................................................234

Attaching a template to a document ...............................................235

Understanding NORMAL.DOTM .......................................................236

Chapter 18: Misc. Formatting Stuff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .239

Automatic Formatting..................................................................................239

Enjoying automagical text.................................................................240

Paragraph formatting tricks..............................................................241

Undoing an AutoFormat ....................................................................242

Disabling the @#$%&! AutoFormat...................................................243

xv

Table of Contents

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xv

Become an Expert in Your Fields ...............................................................244

Inserting a field into your document ...............................................244

Playing with fields ..............................................................................246

Center a Page, Top to Bottom.....................................................................248

Steal This Format! ........................................................................................249

Part IV: Making Your Document

All Fancy-Schmancy..................................................251

Chapter 19: Borders, Boxes, and Background Color . . . . . . . . . . . . . .253

This Border Situation ..................................................................................253

The Border command button...........................................................254

The Borders and Shading dialog box...............................................255

Lines and Boxes Around Your Text............................................................255

Drawing a fat, thick line.....................................................................256

Making rules........................................................................................256

Boxing text or paragraphs.................................................................257

Boxing a title .......................................................................................257

Putting a border around a page of text............................................258

Removing borders..............................................................................259

Background Colors ......................................................................................259

Chapter 20: Turning the Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .261

Furnish Forth the Tables.............................................................................261

Starting your table-creation fun .......................................................262

Creating a table yay-by-yay big.........................................................263

Drawing a table...................................................................................264

Transmuting tabbed text into a table ..............................................266

Turning a table back into plain text.................................................266

It’s Your Turn to Set the Table....................................................................267

Using the mouse with a table............................................................267

Putting text into a table .....................................................................268

Table Craftsmanship....................................................................................269

Designing a table ................................................................................269

Adjusting the table.............................................................................271

Deleting a table...................................................................................272

Chapter 21: Carousing with Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .273

All About Columns .......................................................................................273

Here Come the Columns!.............................................................................275

Making more than three columns ....................................................275

Mixing column formats......................................................................276

Adjusting the columns in the Columns dialog box ........................276

The End of the Column................................................................................277

Word 2007 For Dummies

xvi

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xvi

Chapter 22: I Love Lists . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .279

Basic Bullets and Numbers.........................................................................279

Making a bulleted list.........................................................................280

Numbering a list .................................................................................280

Numbering lines of text .....................................................................281

Lists of Things in Your Document..............................................................281

Creating a table of contents..............................................................282

Building an index................................................................................283

Footnotes and Endnotes .............................................................................286

Chapter 23: Going Graphical . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .289

Here Come the Graphics! ............................................................................290

Inserting a picture from a file on disk..............................................290

Inserting a clip art image...................................................................291

Slapping down an AutoShape ...........................................................292

Inserting a picture or text into an AutoShape ................................293

Deleting an image or artwork ...........................................................294

Images and Text Can Mix ............................................................................294

Wrapping text around the image......................................................295

Moving an image hither and thither ................................................296

Image Editing ................................................................................................297

Changing an image’s size...................................................................298

Cropping an image .............................................................................298

Rotating the image .............................................................................299

Arranging multiple images ................................................................299

Chapter 24: Stick

This

in Your Document . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .301

Characters Fun and Funky ..........................................................................301

Nonbreaking spaces and hyphens ...................................................301

Typing characters such as Ü, Ç, and Ñ............................................302

Adding a dash of en or em ................................................................303

Inserting special characters and symbols ......................................303

Say It in WordArt ..........................................................................................304

Spice Up Your Document with a Text Box ................................................306

Instant Graphical Goodness with SmartArt..............................................307

Part V: What Else Is Left?..........................................309

Chapter 25: Multiple Documents, Multiple Windows,

Multiple Formats, Multiple Madness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .311

Multiple Document Mania...........................................................................311

Managing multiple documents .........................................................312

Viewing the same document in multiple windows.........................314

Using the old split-screen trick.........................................................315

xvii

Table of Contents

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xvii

Working with Non-Word Document Formats............................................316

Using the Files Type drop-down list.................................................317

Loading an alien document...............................................................317

Saving a file in a horridly strange and unnatural format...............319

Updating older Word documents .....................................................319

Chapter 26: Other Ways of Viewing a Document . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .321

Organize Your Thoughts .............................................................................322

Entering Outline view ........................................................................322

Adding topics to your outline...........................................................323

Demoting a topic (creating subtopics)............................................324

Promoting a topic...............................................................................325

Adding a text topic.............................................................................326

Rearranging topics .............................................................................326

Expanding and contracting topics ...................................................326

Printing an outline..............................................................................328

Sit Back and Read.........................................................................................328

Chapter 27: Working This Out Together . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .331

Here Are My Thoughts ................................................................................331

Adding a comment .............................................................................332

Hiding comments ...............................................................................333

Reviewing comments.........................................................................333

Printing comments (or not) ..............................................................334

Deleting comments ............................................................................334

Whip Out the Yellow Highlighter................................................................334

Look What They’ve Done to My Text, Ma .................................................335

Comparing two versions of the same document............................335

Reviewing the changes ......................................................................337

Tracking changes as you make them...............................................338

Chapter 28: Merrily We Mail Merge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .339

All About Mail Merge ...................................................................................339

Mail Merge Ho!..............................................................................................340

Creating the main document (Task 1 of 5)......................................341

Assigning fields (Task 2 of 5) ............................................................343

Building records (Task 3 of 5)...........................................................345

Inserting fields into the main document (Task 4 of 5)...................347

Merging it all together (Last task)....................................................348

Chapter 29: Labels of Love . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .351

The Label Thing............................................................................................351

Here’s a Sheet of Identical Labels ..............................................................352

Print That Address List ...............................................................................353

A Label Trick with Graphics .......................................................................355

Word 2007 For Dummies

xviii

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xviii

Chapter 30: Customizing Word . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .357

All the Better to See You, My Dear.............................................................357

The Status Bar Configuration Menu...........................................................359

The Quick Access Toolbar ..........................................................................360

Finding the toolbar.............................................................................360

Moving the toolbar.............................................................................361

Adding command buttons to the toolbar........................................361

Removing commands from the toolbar...........................................363

Restoring the Quick Access toolbar ................................................363

Part VI: The Part of Tens............................................365

Chapter 31: The Ten Commandments of Word . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .367

Thou Shalt Remember to Save Thy Work .................................................367

Thou Shalt Not Use More Than One Space...............................................368

Thou Shalt Not Press Enter at the End of Each Line ...............................368

Thou Shalt Not Neglect Thy Keyboard......................................................368

Thou Shalt Not Manually Number Thy Pages ..........................................369

Thou Shalt Not Use the Enter Key to Start a New Page ..........................369

Thou Shalt Not Click OK Too Quickly........................................................369

Thou Shalt Not Forget Thy Undo Command ............................................369

Honor Thy Printer........................................................................................370

Thou Shalt Have Multiple Document Windows Before Thee .................370

Chapter 32: Ten Cool Tricks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .371

Automatic Save with AutoRecover ............................................................371

Keyboard Power!..........................................................................................372

Build Your Own Fractions ...........................................................................372

Electronic Bookmarks .................................................................................373

Document Inspection...................................................................................374

The Drop Cap................................................................................................374

The Document Map......................................................................................375

Add an Envelope to Your letter ..................................................................376

Sort Your Text...............................................................................................376

Text That Doesn’t Print ...............................................................................377

Chapter 33: Ten Odd Things . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .379

Equations ......................................................................................................379

Math...............................................................................................................380

Document Defense Options ........................................................................381

Hyphenation .................................................................................................381

Document Properties...................................................................................381

The Developer Tab.......................................................................................382

xix

Table of Contents

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xix

Cross-References..........................................................................................382

Smart Tags.....................................................................................................383

Click-and-Type..............................................................................................383

Word and the Internet .................................................................................384

Chapter 34: Ten Avuncular Suggestions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .385

Keep Printer Paper, Toner, and Supplies Handy ......................................385

Get Some References ...................................................................................386

Keep Your Computer Files Organized .......................................................386

Know a Little Windows................................................................................386

Back Up Your Work ......................................................................................387

Use AutoCorrect...........................................................................................387

Use Those Keyboard Shortcuts..................................................................387

Try New Things ............................................................................................388

Let Word Do the Work .................................................................................388

Don’t Take It All Too Seriously ...................................................................388

Index........................................................................389

Word 2007 For Dummies

xx

02_036583 ftoc.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page xx

Introduction

A

re you nervous? Intimidated? Befuddled and confused beyond all

recourse?

What did they do to Word? Just when you thought you finally

had a leg up on the program, just as you finally remembered that the Sort

command is on the Tables menu, they’ve gone and changed . . . everything!

What a headache!

Welcome to

Word 2007 For Dummies, which is a better solution to your word

processing pains than taking two aspirin and calling tech support in the

morning. This book is your friendly, informative, and entertaining guide to

the newfangled way of processing words that is Word 2007.

I’m not telling you that this book will make you all cozy and pleased with the

new ways of Word. No, I’m merely promising that this book eases the pain

everyone feels with Word 2007. Let other authors apologize for the program!

I’m here to kick Word in the butt and, hopefully, you’ll enjoy watching that.

What’s New in Word 2007?

Earlier versions of Word all looked alike. They had menus, toolbars, task

panes, and other pop-up, drop-down, leak-out nonsense. With Word 2007, all

that stuff is gone, nailed shut in a box and wheeled away into that huge ware-

house where the U.S. government keeps the Ark of the Covenant. Word 2007

sports no menus. It has only one tiny toolbar.

Replacing the menus and toolbars is a tabbed Ribbon system. The tabs are

like the menus of old, but their commands are grouped into graphical com-

mand buttons. Some buttons are commands, some buttons are menus. This

setup can be overwhelming at first, but I must admit that it makes it possible

to do some tasks in fewer steps than with the old Word interface. Knowing

that, of course, doesn’t make the thing less intimidating.

Beyond the interface, Word is a bit stricter on styles and formatting. The ben-

efit here is

instant previews, or the ability to instantly see how changes affect

your document as you browse a menu. Part III of this book explains more.

Word’s main mode of operation is Print Layout view. If you were a fan of

Normal or Draft view in previous versions of Word, I highly recommend that

you switch to Print Layout view, if you haven’t already.

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 1

Finally, many commands didn’t survive the transition from older versions of

Word to Word 2007. You won’t find any of the following in Word 2007:

AutoFormat Save All

Close All Save As Web Page

Character Animation Speech

File Search Wizards

Frames WordPerfect Help

Office Assistant

These items were either dropped entirely or replaced with something better.

About This Book

I don’t intend for you to read this book from cover to cover. It’s not a novel,

and if it were, it would be a musical novel and you’d be required to sing the

songs and go through the dances with all the characters in a book and, quite

honestly, I don’t think that the people near you would let you get away with it.

This book is a reference. Each chapter covers a specific topic or task that

Word does. Within a chapter, you find self-contained sections, each of which

describes how to perform a specific task or get something done. Sample sec-

tions you encounter in this book include:

Saving your stuff

Moving a block of text

Quickly finding your place

Aligning paragraphs

Cobbling a table together quickly

Creating a table of contents

Adding topics to your outline

There are no keys to memorize, no secret codes, no tricks, no videos to sleep

through, and no wall charts. Instead, each section explains a topic as though

it’s the first thing you read in this book. Nothing is assumed, and everything

is cross-referenced. Technical terms and topics, when they come up, are

neatly shoved to the side, where you can easily avoid reading them. The idea

here isn’t for you to learn anything. This book’s philosophy is to help you

look it up, figure it out, and get back to work.

2

Word 2007 For Dummies

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 2

How to Use This Book

You hold in your hands an active book. The topics between this book’s

yellow-and-black covers are all geared toward getting things done in Word

2007. Because nothing is assumed, all you need to do is find the topic that

interests you and read.

Word uses the mouse and keyboard to get things done. Still, the program

looks different from traditional Windows programs, so pay attention!

This is a keyboard shortcut:

Ctrl+P

This shortcut means that you should press and hold the Ctrl (control) key

and type a P, just as you would press Shift+P to get a capital P. Sometimes,

more than two keys need to be pressed at the same time:

Ctrl+Shift+T

In this line, you press Ctrl and Shift together and then press the T key.

Release all three keys.

Commands in Word 2007 exist as

command buttons on the Ribbon interface.

This book may refer to the tab, the command group, and then the button

itself to help you locate that command button — for example, the Page

Layout tab, Page Background group, Page Color button. Or, I might say “the

Page Color button found in the Page Layout tab’s Page Background group.

Often times, command buttons are shown in the margin, which can help you

locate them.

Menu commands are listed like this:

Table

➪Insert Table

This command means that you choose the command named Insert Table

from the Table menu. Note that Table is most likely a button on the Ribbon.

The File menu from previous versions of Word now exists as the Microsoft

Office Button menu, which I refer to as the Office Button menu. You still press

Alt+F to access this menu, and it contains items similar to the old File menu.

3

Introduction

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 3

When I describe a message or something you see on-screen, it looks like this:

Why should I bother to learn about compound interest when

robots will eventually destroy the human race?

If you need further help operating your computer or a good general reference,

I can recommend my book

PCs For Dummies, published by Wiley Publishing,

Inc. The book contains lots of useful information to supplement what you find

in this book.

Foolish Assumptions

Though this book was written with the beginner in mind, I still make a

few assumptions. Foremost, I assume that you’re using a computer. You

use Windows as the computer’s operating system, either Windows Vista

or Windows XP or any other version of Windows that can run Word 2007.

There are no specific issues between Word and Windows as far as this book

is concerned, but keep in mind that this book isn’t about Windows.

Your word processor is Microsoft Word 2007. It is

not Microsoft Works. It is

not an earlier version of Word. It is not WordPerfect. It is not a version of

Word that runs on a Macintosh.

Throughout this book, I use “Word 2007” and “Word” interchangeably. Both

refer to the same thing. (Word 2007 may also be referred to as Word 12 in

some instances, although not in this book.)

Word 2007 is a part of the Microsoft Office 2007 suite of programs. This book

doesn’t cover any other part of Microsoft Office, nor do I assume that you

even have the Microsoft Office suite installed.

How This Book Is Organized

This book contains six major parts, each of which is divided into several chap-

ters. The chapters themselves have been sliced into smaller, modular sections.

You can pick up the book and read any section without necessarily knowing

what has already been covered in the rest of the book. Start anywhere.

Here’s a breakdown of the parts and what you can find in them:

4

Word 2007 For Dummies

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 4

Part I: Hello, Word!

This part provides a quick introduction to Word and word processing.

Information is offered on how best to use your keyboard, plus a simple

overview of the typical word processing day. Part I contains lots of good,

basic information.

Part II: Word Processing Basics

The chapters in this part of the book cover the 7 basic tasks of any word

processor: moving around a document, editing text, search and replace,

working with blocks of text, document proofing, saving and opening, and

finally printing.

Part III: Formatting

This part deals with formatting, from the smallest iota of text to formatting

commands that span an entire document and more. Formatting is the art of

making your document look less ugly.

Part IV: Making Your Document

All Fancy-Schmancy

This part is formatting dessert, or things you can do beyond regular format-

ting to help make your document look like more than a typical, boring docu-

ment. It covers lines, borders, tables, columns, lists, graphical goodness, and

all sorts of stuff that makes Word more than a typical word processor.

Part V: What Else Is Left?

This part covers a few dangling details that I consider myself fortunate to

write about, such as outlining, collaboration, mail merge, label-making, and

other interesting things that Word does.

Part VI: The Part of Tens

The traditional last part of any For Dummies book contains chapters with lists

of ten items. You’ll find lots of helpful stuff here, some weird things you may

not know about, plus even more useful tips, tricks, and good suggestions.

5

Introduction

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 5

What’s Not Here

Word is one heck of a program. Covering the entire thing would take a book

several thousand pages long. (I kid you not.) My approach in this book is to

cover as much basic word processing as possible. Because of that, some

advanced features did get pushed off the table of contents.

You won’t find any information here on macros in Word. Although they can be

useful, it’s tough to get into macros without broaching the more technical topic

of Microsoft Office Visual Basic, which is a true programming language —

definitely not beginner stuff.

Some of the more esoteric features are touched upon lightly here. For exam-

ple, I could spend about 70 pages detailing what can be done with graphics in

Word, but I limited myself to only a dozen pages.

Finally, this book doesn’t cover using Word to do anything on the Internet.

That includes using e-mail, making a Web page, blogging, online publishing,

creating forms, or doing that kind of stuff. This is a word processing book,

and Word is a word processor.

Icons Used in This Book

This icon flags useful, helpful tips or shortcuts.

This icon marks a friendly reminder to do something.

This icon marks a friendly reminder

not to do something.

This icon alerts you to overly nerdy information and technical discussions of

the topic at hand. The information is optional reading, but it may enhance

your reputation at cocktail parties if you repeat it.

6

Word 2007 For Dummies

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 6

Where to Go from Here

Start reading! Observe the table of contents and find something that interests

you. Or, look up your puzzle in the index.

Because Word 2007 has changed, whether you’re new to the program or not,

you should start reading at Chapter 1.

Read! Write! Let your brilliance shine on a sheet of paper.

My e-mail address is

dgookin@wambooli.com. Yes, that’s my real address. I

try to reply to all the e-mail I get, although sometimes I’m not that speedy.

And, although I enjoy saying “Hi” or answering questions about this book,

please do not e-mail me with technical support questions or problems with

your computer. For that, I can recommend reading my book

Troubleshooting

Your PC For Dummies

(Wiley).

You can also visit my Web page for more information or as a diversion:

www.wambooli.com. Be sure to check out the Wambooli Forums while

you’re there.

Enjoy the book. And enjoy Word. Or at least tolerate it.

7

Introduction

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 7

8

Word 2007 For Dummies

03_036583 intro.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 8

Part I

Hello, Word!

04_036583 pt01.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 9

In this part . . .

B

lame it all on Homer. One day, he was telling his

epic poem

The Iliad to a crowd of eager Greeks.

The Greeks were thrilled. One Greek in particular was

so enamored with the tale that he blurted out, “This

stuff is great! If only we could remember it all!”

Irritated at being interrupted, Homer replied, “Why not

write it down?”

The Greeks collectively went “Huh?”

Homer explained, “Me? I’m blind. I had to memorize the

whole thing. You — you have sight. You can write it down.

Of course, it would be nifty if you had a word processor,

which would make typing the thing easy, as well as format-

ting and printing it. But you’re thousands of years too early

for that. So my advice is to start by creating an alphabet.

Better still, you’re Greeks: Steal an alphabet.”

And so the long quest began. From the Greek alphabet

to reading and writing for the masses to moveable type to

the fountain pen and the typewriter, and now . . . this, this

word processor, which I introduce to you in the chapters

that comprise this part of the book.

04_036583 pt01.qxp 11/16/06 12:43 PM Page 10

Chapter 1

Word Hokey-Pokey

In This Chapter

Starting Word

Reading the Word screen

Getting help from Word

Exiting Word (or not)

C

heer up! Word processing is one of the best things that a computer can do.

It’s much better than trying to compose your thoughts on a typewriter. It’s

better than worrying about good penmanship. It’s much more efficient than

using Gutenberg’s moveable-type machine. It’s cheaper than paying a scribe to

scribble hieroglyphics on a papyrus roll. And it’s certainly better than chipping

a stone tablet with a rock. Keep that rock handy, though: You may still need

something to smash the computer when it frustrates you.

This chapter provides an overview of Microsoft Word 2007. It’s your introduc-

tion to the newfangled way that people are word processing during this, the

breakfast of the 21st century. So, sit back, relax, grab a refreshing beverage,

and definitely put down that rock! You’ll be on your way to writing words

electric in no time.

How Do I Start Word? Let Me

Count the Ways. . . .

Anyone using a computer suspects that there’s probably a better, faster, or

more serious way to get things done. There are so many options! Who knows

when someone will amble up to you and point at how you start your word

processor. “You do

that?” they’ll snicker and walk away. Oh, no. What now?

The question isn’t really how to start Word, but rather how

best to start Word.

In Windows, there are a bazillion ways to start any program. Other books drag

out every last method, but for starting Word (or any program that you use

05_036583 ch01.qxp 11/16/06 12:44 PM Page 11

often), there are definitely good, better, and best ways. Before going there,

consider taking some general steps before you begin your word processing

odyssey:

1. Ensure that your computer is on and toasty.

Any computer that’s on is, in fact, toasty. The only way to make it

toastier is to insert bread, which I don’t recommend.

2. Prepare yourself physically.

Make sure you’re seated, with a nice, upright, firm posture. They tell me

that your wrists should be even with your elbows and that you shouldn’t

have to tilt your head forward. Shoulders are back and relaxed.

Close your eyes. Unwind. Breathe in, breath out.

3. Prepare yourself mentally.

Yes, you can do this! Hail the muse scribborrhea, the forest nymph of

electronics and typing. Think calm thoughts. Concentrate on letting the

thoughts flow from your brain and rush down your arms and into your

fingers as they dance upon the keyboard. Remember that you are the

master. Mutter that over and over: “I am the master. . . .”

If you need help starting your computer, refer to my book

PCs For Dummies

(Wiley Publishing) for quick and accurate turning-on-the-computer instructions.

You can stop muttering “I am the master” now.

The good, yet unimaginative,

way to start Word

Without fail, the place to start any program in Windows is at the fabled Start

button. It may not be the coolest way to start a program, but it’s consistent

and reliable — good things to have in a computer. Obey these steps:

1. Click the Start button.

Use your computer mouse to click the Start button, which is often found

on the left side of the taskbar, at the bottom of the screen, adorned with

the Windows logo and often (cleverly) the word

Start.

Clicking the Start button displays the Start menu.

2. Choose Word from the All Programs menu.

Now, you may be lucky and see the Word program icon on the Start

menu. If so, click the Word icon to start Word. If not, you have to click the

All Programs menu and look for Word in that vast labyrinth.

12

Part I: Hello, Word!

05_036583 ch01.qxp 11/21/06 10:39 AM Page 12

Behold! Word starts! Watch in amazement as your computer whizzes and

whirs. Before too long, Word appears on the computer’s monitor, trying to be

friendly and inviting but failing utterly.

Don’t let Word’s appearance overwhelm you! I describe what you’re looking

at later, in the section “Behold Word!”

If you can’t find Word on the All Programs menu, look for a submenu

named Microsoft Office or Office 12 or even Office 2007. Word may be

lurking on that submenu.

The Start menu contains a list of many interesting things, including pro-

grams, recently used programs, and fun locations to visit in Windows.

One of those Start menu things is the All Programs menu, which may

also be called Programs (without the word

All).

Supposedly, every program ever installed on your computer has

installed its icon in a spot somewhere on the All Programs menu.

I refer to the program as Word, though the icon may be labeled Microsoft

Word, Microsoft Office Word, Word 2007, or some other clever variation

on that theme.

The better and best ways to start Word

When you use Word a lot, it helps to have quick access to its icon — that icon

is the way you start Word — and then start your work. A better way than

keeping Word hidden on the All Programs menu is to create a Word shortcut

icon on the desktop. Heed these steps:

1. Locate the Word icon on the All Programs menu.

Don’t start Word now! Just point the mouse at the Word icon on the Start

button’s All Programs menu or wherever else it may be found.

13

Chapter 1: Word Hokey-Pokey

Automatically starting Word every

ding-dong time you start Windows

To get your computer to start Word whenever you

start Windows, you need to move the Microsoft

Word item from its current location on the All

Programs menu to the All Programs

➪Startup

folder. The items in the Startup folder start up auto-

matically when Windows begins its day. As with

all things in Windows, there exists a multitude of

ways to accomplish the move. Refer to your

favorite Windows reference for the details, or just

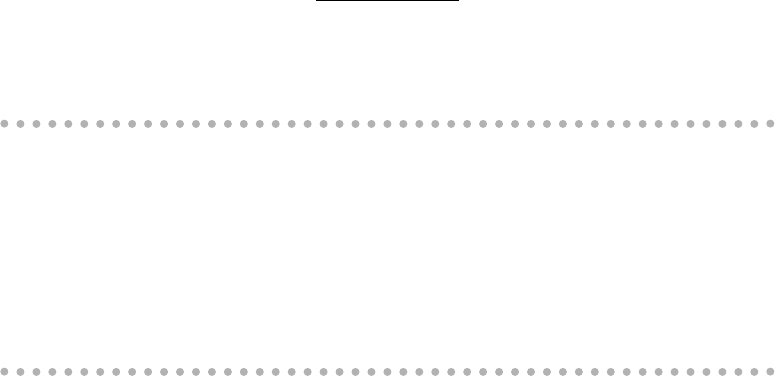

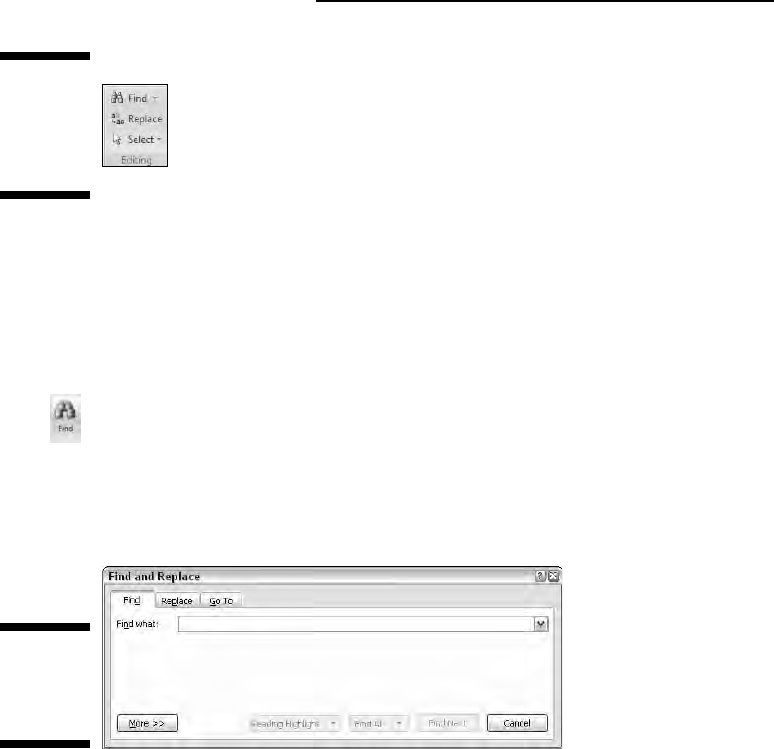

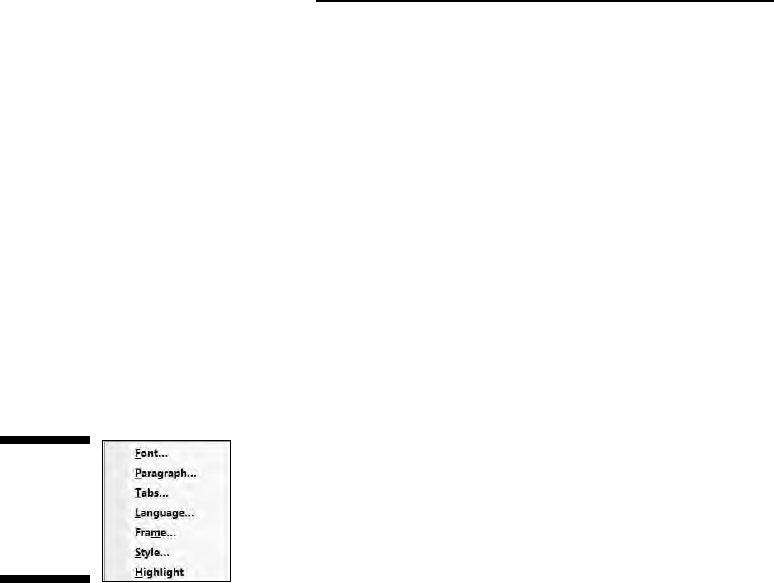

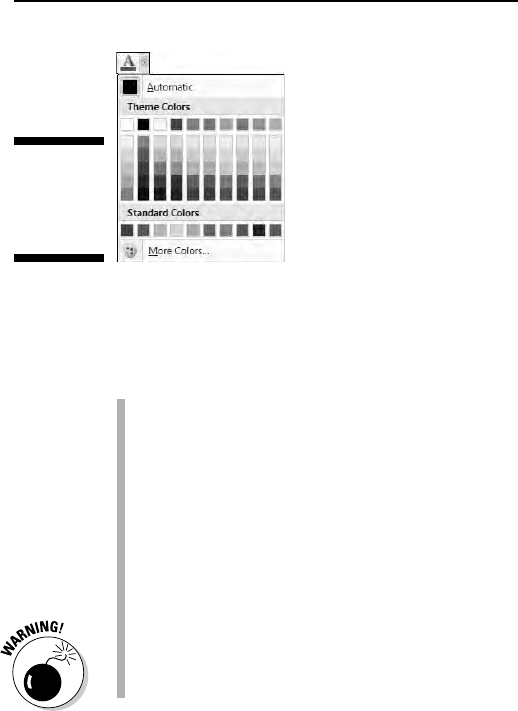

grab someone who looks like a Windows nerd and