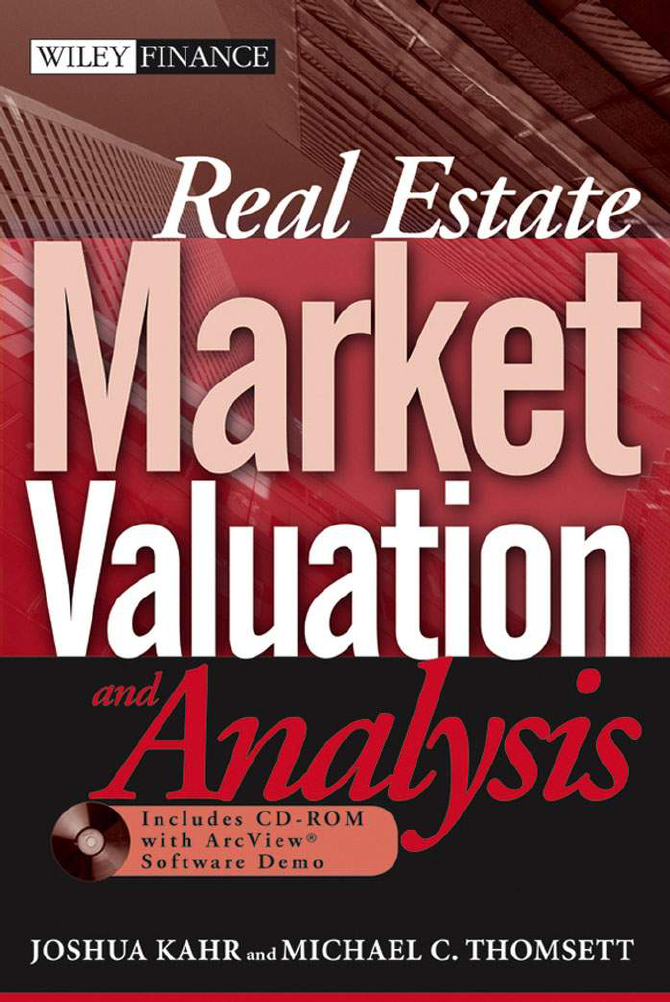

Real Estate Market Valuation and Analysis

JOSHUA KAHR

and

MICHAEL C. THOMSETT

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Real Estate

Market Valuation

and Analysis

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page iii

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page ii

Real Estate

Market Valuation

and Analysis

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page i

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page ii

JOSHUA KAHR

and

MICHAEL C. THOMSETT

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Real Estate

Market Valuation

and Analysis

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page iii

Copyright © 2005 by Joshua Kahr and Michael C. Thomsett. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or

otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States

Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization

through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.,

222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the

web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed

to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ

07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their

best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect

to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any

implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may

be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and

strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a

professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss

of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental,

consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services, or technical support, please

contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at 800-762-2974,

outside the United States at 317-572-3993 or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears

in print may not be available in electronic books.

For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Kahr, Joshua, 1974-

Real estate market valuation and analysis / Joshua Kahr and Michael C.

Thomsett.

p. cm—(Wiley finance series)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-471-65526-8 (cloth/cd-rom)

ISBN-10: 0-471-65526-0 (cloth/cd-rom)

1. Real property—Valuation. 2. Real estate investment. I. Thomsett,

Michael C. II. Title. III. Series.

HD1387.K3135 2005

333.33'2—dc22

2005012597

Printed in the United States of America.

10987654321

ffirs.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page iv

Contents

Preface A

Practical

Approach vii

CHAPTER 1

The Essence of Analysis 1

CHAPTER 2

Using Analysis Effectively 29

CHAPTER 3

Valuation of Real Estate 47

CHAPTER 4

Single-Family Home and Condo Analysis 73

CHAPTER 5

Multi-Unit Rental Property Analysis 99

CHAPTER 6

Retail Real Estate Analysis 119

CHAPTER 7

Office and Industrial Real Estate Analysis 145

CHAPTER 8

Lodging and Tourism Industry Real Estate 161

CHAPTER 9

Mixed-Use Real Estate Analysis 177

v

ftoc.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page v

Internet Sources for Further Study 195

Bibliography 207

Glossary 211

Using a GIS Tool in Real Estate Market Analysis 225

Notes 235

Index 241

vi CONTENTS

ftoc.qxd 8/5/05 12:39 PM Page vi

Preface—A

Practical

Approach

H

ow much is it worth?”

Every investor begins with this question. The question of value is at

the core of the decision. It is the essence of the decision to buy one property

and to reject another.

Value is a complex topic because it is partly subjective and partly deter-

mined by outside forces. A particular piece of property—whether residen-

tial, commercial, or industrial—will be valued based on its location,

improvements, zoning, competition, local employment, and the availability

(or lack of availability) of other, similar properties. For the serious analyst,

the question should be, How is real estate value properly determined?

There are numerous methods and theories available, some scientific and

others utilizing inaccurate statistical bases or national (rather than regional

or local) trends. We propose the use of scientific methods and, at the same

time, an overlay of practical considerations regarding local markets, risk

tolerance, cash flow, experience, tax benefits, and real estate-focused funda-

mental analysis. Just as stock investors recognize the importance of the fun-

damental analytical tools in the selection of stock, the same approach can

and should be used in the analysis of real estate.

It is neither possible nor advisable to try to determine value based

merely on a visual inspection or other nonfundamental indicators. Such de-

cisions are better made based on comparative shopping and analysis and a

thorough comparative approach to the entire real estate market. Ironically,

some investors make a decision to purchase without careful and thorough

analysis and, in some cases, without even defining the means for assigning

value. For some consumers, a property is worth whatever its listed price

may be, or whatever a real estate broker says. Considering that the same

consumers are likely to purchase automobiles with greater care, this is a

puzzling way to buy real estate. A car buyer will likely visit two or more

dealers and, at the very least, take cars out for a test drive. Why compari-

son shop for $20,000 cars but impulse-buy a $250,000 investment prop-

erty or residence?

The example of the impulse-buying real estate buyer is the extreme.

Most people are not that impulsive. However, real estate investors are faced

with the problem of how to analyze real estate values and, if they are to

vii

“

fpref.qxd 8/5/05 12:40 PM Page vii

succeed, they also need to develop the means for reliably analyzing the real

estate they are considering buying. What factors determine value? What

are the appropriate means for comparison between like-kind properties?

Why does a subtle difference in location make a vast difference in price?

These and similar questions are enormous challenges for the real estate

investor. We cannot shop for property based on a single criterion, and we

cannot limit our examination to the same criteria in all cases. For example,

it is not prudent to shop for commercial rental property using the same val-

uation methods as we use when buying residential property. We cannot

even make the same underlying assumptions about two similar properties

in different locations. The collective economic, demographic, and local fac-

tors affecting real estate values have to be studied and analyzed collectively

if we are to make an informed decision. Real estate analysis can be per-

formed by anyone; however, it is not enough to place trust in a broker or

seller, and we cannot pick real estate from classified advertising. Those me-

dia are starting points in the search; informed decisions rely on more de-

tailed analysis and study.

It is a mistake to rely on others to identify value without further study.

Even so, a vast number of investors do not ask the right questions or even

know what questions to ask. Those who do inquire usually limit their dia-

logue to one with a real estate broker, who may not even be conversant in

the art of real estate analysis. Most state tests for real estate licensing are

surprisingly easy and require little in the way of actual analytical knowl-

edge. Emphasis is usually placed on more mundane matters such as know-

ing how to fill in the standard forms for real estate contracts; agent and

broker liability and how to prevent it; and knowing about buyer and seller

rights and duties. Few real estate agents can provide advice on estimating

cash flow, analyzing relative value and investment potential, or the current

state of local supply and demand.

Even so, the buying public (including many mom-and-pop investors)

presumes that the real estate broker has the answers. The broker’s job is to

move property onto the market, and the more properties they close, the

more commission they earn. Emphasis is placed on bringing together a

willing seller and a willing buyer. But as many prospective buyers often

overlook, the broker usually works for the seller. Consequently, so the

process of real estate analysis—which is of greater interest to buyers than

to sellers—is not within the bundle of motivations that the broker has in

mind. Therefore, if you do not know how to critically analyze real estate

values and you depend on the assurances of a broker, you are on your own.

This book addresses the problems of analyzing real estate with several

possible readers in mind. A number of investors allocate a portion of their

capital to real estate through direct ownership, partnerships, or pooled in-

viii PREFACE: A PRACTICAL APPROACH

fpref.qxd 8/5/05 12:40 PM Page viii

vestments (mortgage pools, for example, operate much like mutual funds,

with portfolios consisting of mortgage debt rather than stocks or bonds).

Business and real estate students and professors will also find this reference

to be valuable in developing—at the very least—an approach to issues of

valuation and investment in real estate.

The book has been organized to present material in a practical manner.

What does this mean? Many years ago, a workshop was held at a confer-

ence for stockbrokers. One of the audience members asked a panel, “How

can we do a better job helping our clients to make investment decisions?”

One of the panel members advised, “Pretend it’s real money.”

We are going to offer the same advice in this book. When we use the-

ory by itself, we can have all of the answers. However, to make theory

practical, we also need to provoke thought within ourselves. We ask basic

questions and try to provide answers that may surprise many readers.

Good rule-of-thumb advice, whether conceptual or practical, is valuable as

a starting point; but we want to go beyond, to help our readers to think of

money invested in the real estate market as real money, and not just as an

exercise in the theoretical process of investing.

We begin with three chapters that discuss real estate analysis overall.

These topics are essential for all investors, consumers, and students of real

estate topics. Chapters 4 through 6 discuss specific popular types of prop-

erty and isolate their unique features. The analysis of each type of real es-

tate rests largely with the features each type of property contains. Thus,

valuation of single-family residences (Chapter 4) will not be identical to the

process of analysis for multi-unit properties (Chapter 5) or retail properties

(Chapter 6). Chapters 7 through 9 examine valuation and means for analy-

sis of nonresidential investment properties: office and industrial (Chapter

7), lodging and tourism (Chapter 8), and mixed-use real estate (Chapter 9).

Throughout the book, our goal has been to provide useful tools in the

form of statistical information, examples, charts and graphs, and case

studies. The organization and format of the book is intended to ensure that

the information can be absorbed and converted to practical applications.

Preface: A Practical Approach ix

fpref.qxd 8/5/05 12:40 PM Page ix

fpref.qxd 8/5/05 12:40 PM Page x

CHAPTER

1

The Essence of Analysis

Analysis is an elusive process; whether investor, appraiser, or

student, understanding the essential points to consider is itself a

difficult process. In this chapter, we introduce the fundamental

methodology as a starting point for deciding whether an

investment makes sense. We examine the question, Who uses

market analysis and why? Finally, we demonstrate how raising

capital for investment purposes must be premised on a foundation

of solid analysis.

K

nowing the right questions to ask is a wise starting point in any inquisi-

tive task. Otherwise, we cannot identify the underlying assumptions nec-

essary to arrive at an informed conclusion. A market analysis may have

several different meanings, just as a real estate market is not necessarily go-

ing to mean the same thing to different people. We recognize a definition of

real estate market as

the interaction of individuals who exchange real property rights

for other assets, such as money. Specific real estate markets are de-

fined on the basis of property type, location, income-producing

potential, typical investor characteristics, typical tenant character-

istics, or other attributes recognized by those participating in the

exchange of real property.

1

We also need to recognize that analysis may fall into several distinct

and separate functions within the broad function of market analysis.

1

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 1

BASIC MARKET ANALYSIS CONCEPT—AN OVERVIEW

We view market analysis as a broad overview of supply and demand attrib-

utes for property, including site-specific and local factors and current as

well as emerging competition. To begin, we provide some basic definitions.

Additional definitions may also be found in the book’s Glossary. Studies

that focus on the market include:

Analysis of local economies: Studies the fundamental determinants of

the demand for all real estate in the market.

Market analysis: Studies the demand for and supply of a particular

property type in the market.

Marketability analysis: Examines a specific development or property to

assess its competitive position in the market.

Studies that focus on individual decisions include:

Feasibility analysis: Evaluates a specific project as to whether it is

likely to be carried out successfully if pursued under a proposed

program. May relate to developability. Most often related to finan-

cial feasibility.

Investment Analysis: Evaluates a specific property as a potential in-

vestment. Usually incorporates specific financing in the analysis,

and may evaluate alternative financing options to select most ap-

propriate financing or consideration of income taxes. Emphasis is

on risk and reward, sensitivity analysis, and internal rate of return.

With these definitions in mind, the value of the market analysis be-

comes apparent. It is a study that tries to identify the market for a particu-

lar real estate product. Why would we want to understand the market?

Real estate markets are not efficient markets like the stock market, and

pricing does not occur every day.

Whenever someone undertakes a real estate transaction, a market

analysis must be performed. This could range from an informal process to

a two-inch-thick book.

Three key questions should be answered by the study:

1. Will there be users to rent or buy the proposed product?

2. How quickly and at what rent or price will the proposed project be ab-

sorbed in the market?

3. How might the project be planned or marketed to make it more com-

petitive in its market?

2 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 2

In market analysis, three phases are involved: collection of data, analy-

sis, and recommendations. It all starts with data, which may be found in

many places.

Primary, or raw data is unanalyzed, often collected in person by the

analyst. It may include reading classified ads, new development announce-

ments and legal notices, or Census data. Secondary data has gone through

the analytical process by someone else, who tells the analyst what to con-

clude. Secondary data has bias.

The analyst needs to consider bias for all types of data. For example,

even primary data may include unintentional bias. Even Census data may

include undercounts of immigrants, as one example. Secondary data helps

the analyst develop a sense of the market, but primary data is much more

valuable and accurate.

Think of the data as coming from two sides—demand and supply—

and in that order. Why? On the demand side, the analyst includes:

■ Population, number of households, and demographic characteristics.

■

Income, affordability, and purchasing power.

■

Employment, by industry or occupation.

■

Migration and commuting patterns.

■

Other factors.

On the supply side, the following are included:

■ Inventory of existing space or units.

■

Vacancy rates and character of existing property inventory.

■

Recent absorption of space, including types of tenants or buyers.

■

Projects currently under construction and proposed.

■

Market rents/sale prices and how they differ by location and quality.

■

Features, functions, and advantages of existing and proposed projects.

■

Terms and concessions.

Information sources are not limited, either. Analysts may include,

among other sources newspapers, Census and private databases, tax rolls,

advertisements, and maps—in other words, any source that reveals some-

thing of interest.

The value of direct interviews should not be forgotten in this informa-

tion-gathering process. The analyst may interview brokers, owners, urban

planners, local officials, and so on. Interviews provide guidance and open

the analyst’s eyes. The goal in the interview is to ask as many people as

many questions needed to understand the marketplace in order to synthe-

size a complete picture.

Basic Market Analysis Concept—An Overview 3

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 3

The data gathering process should be thought of as competitive intelli-

gence. Market analysis should be tied in with an understanding of the psy-

chology of the different players. In order to understand whether a

proposed project is real, we need to understand the game of business. It is

not enough to just say what is going on; we need to understand the players

involved. Going even further, it is not just enough to know the players. The

analyst also needs to know the local government. In the real estate busi-

ness, government is your largest partner. If you want to do a project, you

need to understand how the political framework either supports or hinders

you based on the desires of elected officials.

Market analysis is generated by virtually everyone in real estate:

Private Sources of Analysis

Appraisers.

Brokers (leasing and sales).

Developers.

Investors.

Asset managers.

Lenders.

Public Sources of Analysis

Urban planners.

Economic development consultants.

Public agencies.

It is interesting to determine—and to study—whether private and pub-

lic analyses mesh or even agree in their conclusions. There are certain ways

that the two sides may be specifically biased. In the private sector, market

analysis is used to maximize profits (and to reduce losses by reducing mar-

ket risks). However, the goals of the public sector are often quite different,

including a context of impacts beyond profitability or feasibility, such as

density, traffic, or design.

Is there such a thing as an unbiased analysis? The answer: Yes. Which-

ever one you are doing.

The serious analyst—absence of bias aside—should be keenly aware

that the process itself invites bias. The analyst cannot fall in love with a

project and remain objective.

One effective method for identifying market analysis is by taking

note of which group or groups use the analysis. These may include

4 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 4

developers/builders, investors and lenders, designers, marketing managers,

local governments, appraisers, assessors, tenants and occupants, sellers,

purchasers, landowners, and property managers. Within the context of

identifying the end-user, it also is important to note that the market

analysis data feeds into the process of feasibility analysis. The two

phases—market and feasibility—are directly affected by the analyst’s

conclusions about market area.

Defining the market area can be broken down into attributes of the

question, What location and physical space make up the market area? This

includes natural features, constructed barriers, population density, political

boundaries, neighborhood boundaries, type and scope of development,

and location of the competition. This level of analysis next leads to a study

of primary and secondary trade areas. Some important considerations de-

fine how accurate the analyst’s work will be. For example, do you use geo-

graphic rings to define the trade area? Putting it another way, is the trade

area a circle? In practice, trade areas are actually formed by travel time and

other market factors, and true trade areas are rarely suitable to explain

with the use of perfect circles. For example, residential zoning and com-

mercial clusters may more accurately define the trade area.

Following the gathering of data, the next step is to analyze. A site’s ad-

vantages and disadvantages can be studied and compared in terms of zon-

ing and comparisons to the competition: location/linkage to other services

and properties, rent or purchase price, unit sizes, occupancy costs, parking

ratios, building/project amenities, technology, security, and maintenance

(current expense level and any deferred maintenance).

In performing the range of analytical tasks, one aspect of real estate

valuation within the broader scope is the more concentrated analysis of lo-

cal economics. This study of supply and demand is viewed as specific to a

narrowly focused region or city. Furthermore, whereas market analysis

tends to be associated with the economic conditions affecting valuation of

a particular property or property type, analysis of local economics applies

to all real estate within a region.

We also want to make a clear distinction between market analysis and

marketability analysis. The latter is a study of the relative competitive posi-

tion of a project within the existing market and anticipated market trends

in the near future.

While studies such as these (market analysis, local economics, and

marketability) tend to be broad-view market studies, two additional types

of analyses are more specific to a particular project. First is the process of

feasibility analysis, which is intended as a study of whether the numbers

work, given the current perception about how a project should proceed,

what it will cost, and who will buy or rent the property. The range of

Basic Market Analysis Concept—An Overview 5

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 5

analysis includes a feasibility study, which we examine later in this chapter.

However, the analysis is a larger process focused on financial questions but

intended as a critical review. If the financial aspects of the project are im-

practical, it needs to be modified so that questions relating to financial fea-

sibility produce more favorable answers.

A related process is called investment analysis, and it looks at the

same financial questions but from the investor’s point of view. Feasibil-

ity—usually associated with developers and project management—is a

part of the developer’s market analysis, whereas investment analysis

takes the same issues and examines them with a different set of choices.

A developer may tend to compare various projects, sites, and real estate

markets; an investor is likely to compare potential real estate invest-

ments to nonreal estate alternatives as well. The investor will, of course,

review financing considerations as part of the analysis; however, financ-

ing is not isolated to investors alone. Lenders and potential lenders will

perform a variation of investment analysis to analyze risk and to identify

the most appropriate type of project financing. Overall, investment

analysis, whether performed on behalf of equity investors or potential

lenders, will want to include an analysis of cash flow, tax benefits and

costs, and comparative return analysis.

To what extent should analysis go? Is it expensive, formal, and time-

consuming in all situations, or should the extent of the process be deter-

mined by the project? For an experienced speculator, for example, who is

familiar with local conditions and trends, an analysis may include a quick

and informal study of a specific property. For an outsider, analysis may in-

volve a more detailed study. For someone requiring local approval or ex-

tensive financing, that analysis may be a thorough research on many levels.

An expanded definition explains how analysis continues to work after

initial decisions have been made concerning where, when, and how to

build a project. Market analysis and research are not isolated functions oc-

curring only at the very front processes of the project but are best utilized

throughout:

Market analysis is a crucial part of the initial feasibility study for a

real estate project, but it does not end there. Market research con-

tinues to play an important role in shaping the project throughout

its development and management phases. Market analysts are

commonly consulted for repositioning strategies after a project is

up and running and the developer realizes that absorption does

not meet projections. As many types of market analysis exist as

variations in development projects, stages of development, and in-

terests being served.

2

6 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 6

In its final form, analysis may be published as a market study or a

feasibility study. In some cases, these are one and the same. How-

ever, we make a clear distinction. Market analysis, as a collective

process, includes an identification of the timing for demand; the

direct relationship between demand and supply (the analysis of

which should consider the role of competition), and calculations

of investment rates of return.

MARKET STUDY AND FEASIBILITY STUDY:

THE DISTINCTIONS

A market study should always begin by answering specific questions that

may be raised by lenders or equity partners, or by investors themselves.

The document has added value as well. For example, regarding subdivision

developments, a survey among developers and bankers concluded “that a

well-documented market survey was a key component of the appraiser’s re-

port.”

3

Such a survey often is mandatory in defining the market area itself.

That definition phase should be the first step, according to a real estate re-

search company’s president, who also advises that “all market analysis

should focus on three basic areas of evaluation: the site, the demand for the

product, and the supply of comparable products.

4

The issues of site plus supply and demand analysis lead us to a series of

critical questions:

1. Is there adequate demand for the improvements existing or proposed,

so that assumed vacancies will be low? This should include analysis of

population demographics, income, employment, and growth forecasts.

Additional market components beyond the analysis of supply and de-

mand may go to price segmentation and coordination with mar-

ketability (development concept in the context of the market, current

available sites versus what end-users want, and market absorption

analysis, for example).

2. Is there a market demand for such improvements and how readily will

the development be sold on the market? How will the proposed devel-

opment impact on current supply in the immediate area (local market)

and the broader market (regional)?

3. How will the development be paid for, and what is the source of

funds?

These three questions will be expressed in the next chapter in a some-

what different form, that of supply and demand. We recognize three forms

Market Study and Feasibility Study: The Distinctions 7

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 7

of supply and demand, involving tenants, real estate acquisition/sale, and

financing. For now, we want to review these important questions and even

expand upon them in defining the scope of a market study. To continue, a

market study will also include the following questions, concerned with

marketability rather than with the conditions of the market:

4. What competitive developments exist and how should this project

be designed, planned, and marketed to effectively compete? In other

words, what is the specific development concept in terms of site

plan, architecture, design, and the proposed market itself (tenant,

shopper, user)?

5. What relevant factors affect our determination of the market? (Con-

sider the effects of local employment trends, population mix, and

even the existence or lack of similar properties.) What is needed in

the market today, and how does this development address that de-

mand? Can the design and concept of this development be improved,

and if so, how?

These five questions—involving questions of supply and demand—are

at the heart of the market study. In comparison, a feasibility study focuses

on financial aspects of a proposed development or acquisition. While the fi-

nancial aspects of market analysis and valuation may be viewed as coldly

factual, a lot of room for interpretation is likely to be found. The numbers

reflect varying forms of reality, but the whole question comes back to sup-

ply and demand and the marketability of a project concept. Expressing this

in market terms, “three possible courses of action . . . exist in real estate

feasibility: (1) a site in search of a use, (2) a use in search of a site, and (3)

an investor looking for a means of participation.”

5

What is the purpose of the feasibility study? If we view it simply as a

means for crunching numbers, then the value of the report will be limited.

In fact, number crunching can and should provide a developer, builder, or

potential investor with a far more important outcome: the determination

of whether the risks of proceeding are justified. A skeptical approach—as-

suming a project will not work—is often a smart approach. One business

consultant explained this aspect of feasibility:

The first goal of a feasibility study or business plan should be

to determine whether or not the potential entrepreneur should

actually take the plunge . . . the default conclusion should be

that the [project] will not succeed. Thus, the plan must convince

potential investors [and] lenders . . . that the [project] will

succeed.

6

8 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 8

Another expert has observed that the process of feasibility analysis

should relate more to what will work and less to what the costs will be, a

concept that often is forgotten in numbers-oriented feasibility work. That

expert observed that

. . . the steps necessary to evaluate the economic feasibility of a

project are frequently confused with a variety of other tasks. Of-

ten this confusion leads to the recital of various statistics dealing

with population size, growth rates, average income, median home

selling price, employment growth, unemployment listings, and the

like. Too often the result is that pure statistical information is sub-

stituted for the analytical process necessary to determine the eco-

nomic feasibility of a project. . . . Some believe the [analyst’s] role

should be limited to answering the question “what is it worth?”

and leaving the question “will it work?” to others.”

7

We can accurately define feasibility—at least in part—as the matching

between various elements of supply and demand, expressed in terms of

cost and benefit. The kinds of questions you will find in a feasibility study

are broader in scope because these various elements are complex; however,

the primary areas involved will include:

■

What is the target market for the proposed development? (In retail

projects, the target has two components: potential tenant stores, and

shoppers, so the target needs to be evaluated with both of these groups

in mind. In residential projects, the target may be either a home-buying

family or a renter, depending on the project and scope envisioned in

the development process. Mixed-use projects are especially complex

regarding target markets. For example, in urban areas such as Man-

hattan, some projects involve retail shopping areas and hotel, residen-

tial, and recreational features in a single complex.

■

What comparable properties are on the market, and how will competi-

tion affect pricing in our case? (If a lot of similar properties exist, does

it make sense to build another? If so, why?)

■

What is the performance level and market demand of the competition?

(This may include vacancy rates in multi-family complexes or sales in a

mall, for example.)

■

What level of financial performance is projected? Specifically, the feasi-

bility study works like the well-known business plan model in its pro-

jection of cash flow, intended to demonstrate that the proposed project

will remain solvent even with a reasonable assumption about vacancy

rates, market rental rates, and seasonal variation. Both investors and

Market Study and Feasibility Study: The Distinctions 9

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 9

lenders will also be keenly interested in conclusions drawn concerning

the cash flow impact of debt financing and the impact—positive or

negative—of taxes.

■

What risks are faced in investing in this project (for equity partners) or

in lending money to finance this project (for lenders)? The range of

risks may involve negative cash flow caused by high vacancies and

unanticipated expenses, changes in the local economic climate, and re-

versal of current demographic trends; the feasibility study should raise

all of these questions.

WHAT SHOULD A MARKET AND FEASIBILITY

STUDY CONTAIN?

While there is no set format for the study document, the typical market

analysis will contain the following items:

Cover page—The type of study, address of property, and names of the

team members.

Letter of transmittal—Major findings, conclusions, and recommen-

dations.

Table of contents—A list of all the sections.

Nature of the assignment—Description of the assignment, methodolo-

gies, and approaches used, and the scope of services undertaken.

Economic background—Establishes the market framework; discusses

the larger market areas first (i.e., regions and/or cities) and the

smaller market areas last (i.e. neighborhoods). Analysts should be

sure to cover all the influences: physical, economic, governmental,

and sociological.

Description of the property and proposed development—A descrip-

tion of the site and improvements should be provided separately.

This section explains the physical and economic plan proposed

for the site.

Competitive developments—While the economic background will in-

clude market data on the competitive supply, this section should in-

clude details on the development’s most significant competition

(existing, planned, and proposed). It should include rental rates and

sale prices, vacancy rates, size of projects, and other information.

Market potential—Here the analyst establishes how well the proposed

development will capture demand in light of the economic back-

10 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 10

ground and compared to the competitive developments. This is the

place to quantify demand for the development. Where does the de-

mand come from for the proposed plan? How is your proposed

plan different or the same as the competition?

Conclusion of marketability—This section should not include any

new data. This is the part dedicated to pure analysis. Everything

included in the body of the report analysis so far is used to make

a case for how the proposed development will compete in the

marketplace.

A 10-year pro forma should be used, based on an assumed

sale of the property at the end of year 10. The pro forma will re-

quire certain assumptions about rental rates, vacancy rates, ab-

sorption rates, and operating expenses. If the proposal is for a

condominium development, the concept is the same, but an appro-

priately shorter holding period should be used.

Addendum—This section is used for any supporting documents such

as site plans, maps, and material supporting other sections of

the report.

Exhibits—In specific sections or as an appendix, include valuable addi-

tional items, including a map identifying the location of the sub-

ject, competitive developments, and the market area; photographs

of the subject property, its block front and the block facing it; and

schedules of competition (size, rent/sale price, and vacancy).

This format is meant only as a guideline. Actual format should be dic-

tated by materials needed to make the case; the unique attributes of the

proposal; and a mandate given to the analyst as part of the assignment.

The reporting format may include both market and feasibility study

features. The distinctions between the two types of studies demonstrate

that the range of requirements for thorough market analysis is comprehen-

sive. An important difference to remember is that the market study may re-

main relevant for a considerable period of time, whereas a feasibility study

is likely to evolve as financial realities change, including employment, con-

struction and land costs, and other economic data (market rents for resi-

dential, lodging, office, and industrial properties, for example). The

problem of reliability in a feasibility study in the lodging industry has been

expressed by a market expert:

Are feasibility studies accurate? They probably are at the time they

are performed. But hotel markets are highly dynamic, and unfore-

seen changes . . . can have a devastating effect on a hotel’s future

What Should a Market and Feasibility Study Contain? 11

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 11

operating performance. With all these interrelated factors (positive

and negative) occurring in a highly random pattern, predicting the

future income and expense of a hotel is like determining the Dow

Jones average three years from now.

8

THE FIRST STEP IN THE MARKET STUDY:

MARKET AREA

The market study is usually the result of thorough market analysis; but

what form does this report take? In order to make this study useful to the

reader (whether approval-granting agencies, equity partners, or lenders),

the study should be organized in a logical manner, so that information pre-

sents a clear picture of the market in all of its meanings; so that important

information can be easily located; and so that decisions can be made.

As with all well-organized reports, the body of the report should be in

a narrative form, with supporting documentation within the report pro-

vided in graphic forms; and with detailed supporting documentation pro-

vided in appendix form. This format makes the report easy to read and

digest; it keeps the body of the report fairly short (even when the support-

ing back matter is voluminous); and it highlights and explains four key ar-

eas of evaluation: overall market area, location-specific factors, demand

factors, and supply of comparable properties.

These four aspects of the market analysis are designed to ask critical

questions. In other words, if we are able to demonstrate that the market

area, location, demand, and supply elements favor proceeding, then it

would make sense to others as well. Equally important, if in the process

of performing market analysis, we are unable to make a convincing case

for the project, then why would anyone else want to proceed? The pur-

pose to market analysis is to critically evaluate the underlying questions,

and to determine whether or not the market is situated so that the project

should proceed.

The starting point is a study of the market area. This is the range in

which supply and demand operates. Traditionally, market area has been

analyzed on the basis of studying the land physically. Today, however, new

technology has expanded the potential of market area analysis, explained

in one real estate book as being a new tool to assist market analysts in

many ways:

Although analysts have traditionally been forced to approximate

market areas by using census tracts, zip codes, or county bound-

aries because of data limitations, emerging geographic information

12 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 12

systems (GIS) technology, or electronic mapping, is liberating real

estate decision makers from relying on arbitrary boundaries.

9

This new technology enables the analyst to look at geographical infor-

mation from a truly big picture view. Artificial boundaries do, indeed, ob-

scure the true market area in many instances. For example, a retail

shopping center would be designed to serve a specific population and geo-

graphical market area, which also makes it possible to estimate the reason-

able assumptions concerning traffic volume and potential sales. However, a

careful study of the market area may point out that the results are not al-

ways as obvious as they may seem at first glance.

Everyone will agree that market area is an important starting point.

You will want to identify the regional realities defining the potential

The First Step in the Market Study: Market Area 13

CASE STUDY: BELLIS FAIR, WASHINGTON STATE

In the typical market area analysis for a retail shopping center, we

would study local population in order to determine whether a project

is supported by the market. This does not always work, however; you

also need to study the specific area to determine how market forces

work. In Bellingham, Washington, the regional mall called Bellis Fair

opened in 1988 on Interstate 5 in Whatcom County. At the time,

many people criticized the plan for this development, arguing that the

local population could not support the mall. Population at the time in

the largely rural county was only about 120,000 (as of 2004, What-

com County, Washington’s population is 157,477). However, Bellis

Fair has been a huge success.

Daily shopper traffic exceeds 35,000 people. The mall has 150

stores, with anchors of Bon-Macy’s, J.C. Penney, Mervyn’s, Sears, and

Target. Overall, Bellis Fair has 768,906 square feet of leaseable store

area on its single level, and 4,730 parking spaces.

How is it possible? The location—Bellingham—is the largest city,

but its population is less than 70,000. The closest large city in Wash-

ington is Seattle, nearly two hours to the south. Bellis Fair is not a

destination from that distance, so where is this market coming from?

The answer: Canada. Bellis Fair is a mere 23 miles from the busiest

border crossing, known as the Peace Arch. Here, U.S. Interstate 5

(Continued)

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 13

market itself. One modern tool worth using for the more complex mar-

ket area studies is Geographic Information Systems (GIS). These systems

may include any database with the ability to indicate a geographical lo-

cation or spatial dimension for the variables in the database....

10

Given

the case history of Bellis Fair, it is clear that such regional factors are not

always obvious. In any modern market area study, GIS would very likely

uncover valuable insights for similar project studies. Additional market

analyses may also be required beyond the geographic location of a per-

ceived market. Some guidelines:

■

Identify the region not only in geographical terms, but also in terms of

where the market exists.

■

The market area for tenants may be drawn from the immediate area as

well as from other areas. For example, with residential projects this

14 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

CASE STUDY: BELLIS FAIR, WASHINGTON STATE (Continued)

crosses into British Columbia. The metro Vancouver region (the area

encompassing the border, north to the suburbs of Vancouver itself)

has more than four million population. This is the dominant market

area for Bellis Fair. A majority of shoppers in Bellis Fair come from

Canada. The current exchange rate is 80 cents of Canadian to U.S.

dollars, so Canadian shoppers enjoy a 20 percent discount by taking a

short trip south. Given the added impact of high Canadian sales

taxes, shoppers have even greater incentive to shop south of the bor-

der. British Columbia sales tax is 7.5 percent (as of 2004), plus federal

taxes of 7.0 percent paid by all Canadians. So shopping at home costs

15.5 percent on top of the retail price, compared to a Washington

State tax rate of about 8 percent.

Conclusion: Any market area study must look realistically at the

effective market. The border between the United States and Canada

(or between any two states) is artificial in terms of market area. It

would be inaccurate for Kansas City, Kansas, to draw conclusions

limited only to Kansas residents; obviously, the larger Kansas City,

Missouri, market would dominate the market area. The same ratio-

nale applies in the case of Bellis Fair. The local population could not

support a larger retail mall (daily traffic exceeds one-fourth of the

county’s population). The success of this mall has to be defined in

terms of broader economic and demographic forces.

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 14

could be related to the location of employment and ease of access to

transit lines.

■

Any project’s analysis should include consideration for how the new

project will affect existing projects. For example, meeting an assumed

demand for residential housing may lead to higher vacancy rates in ex-

isting multi-unit developments.

■

Be aware of the differences between artificial boundaries (county lines,

state borders, etc.) and built boundaries like freeways that cut through

neighbors, thus defining or restricting a market area.

■

Be aware of historical patterns of development based on ethnic or cul-

tural ties. These boundaries change and evolve over time, but they are

remarkably persistent.

■

Be cautious in making undocumented assumptions concerning the ap-

propriate size of a development or the size of an existing market area.

Initial assumptions should be studied critically and conclusions should

be subjected to testing.

THE SECOND STEP IN MARKET ANALYSIS:

SITE EVALUATION

Studying the market area enables us to take a broad view of the region.

Clearly, the features of one area over another will vary considerably, and

the factors are not always obvious. The features within an area affect the

conclusions. For example, an interstate freeway, major border crossing, or

employment trends in one city or region are going to significantly impact

your conclusions about the market area. This leads into the second step,

the more specific site evaluation.

A site evaluation should include comparative analysis—site to site—of

physical properties such as topography, shape of the land, surrounding

uses, and proximity to important features (such as transportation, for ex-

ample). Comparative analysis helps you to assess a particular property or

series of potential sites with features in mind. A shopping mall situated

near a freeway exit would, naturally, have greater potential than one out-

side the city limits and away from the visibility of potential shoppers, the

convenience of access via roads and transit stations, and the overall practi-

cality of siting a shopping mall on well traveled routes. For residential

property, local transit and access to conveniences such as schools and

shopping, also play an important role in comparative site evaluation.

While it may be obvious to some, it is important that the analyst walk the

The Second Step in Market Analysis: Site Evaluation 15

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 15

site. Sound real estate analysis cannot be done thoroughly from a desk or,

for that matter, from behind the wheel of a car.

The question of zoning cannot be overlooked in site analysis, either.

We cannot simply assume that, given the acquisition of land for a specific

purpose, a rezone is automatically going to be granted. Lower-priced prop-

erty may be so priced due to its current zoning, and local authorities (not

to mention citizens living nearby) are likely to resist a rezone merely for the

convenience (and profit) of development interests. On the other hand, in

some cases approval for rezoning is relatively easy to obtain if the new pro-

ject will benefit the community and local government through increased

tax revenues. The potential problems of investing in land when zoning

problems may arise is one risk factor in the site evaluation. You may need

to compare overlooked but potentially profitable land with more obvious

sites. The cost of already-zoned commercial land may be far higher, but the

risk of antigrowth movements among citizens, or denial of rezone applica-

tions by local governments, is largely removed when zoning issues are not

on the table.

The many questions that arise in site evaluation apply to every type of

land use. The questions include whether a particular site is appropriate for

the planned use; whether it is the best available property; whether there are

amenities close by (public recreation, shopping, schools, etc.); and the

larger question of whether citizens and local government would welcome

your planned use.

Potential resistance to your proposal may exist even when zoning is in

place. Those states that have enacted growth management legislation may

impose restrictive growth limitations.

For example, a common principle in growth management laws is that

a specifically identified urban growth area (UGA) should be in-filled be-

fore any new development is to be allowed outside its boundaries. While

intended as a means for preventing urban sprawl, the actual result may

be draconian density within the urban fringe with little or no growth on

the outside.

For the purpose of site evaluation, it is crucial that you also check state

16 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

Valuable Resource

A web site linked to many of the state growth management sites, and iden-

tifying additional useful publications on the topics, is http://www.realtor

.org/sg3.nsf/pages/landusezonegrowmgmt?OpenDocument

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 16

and local laws beyond mere zoning. The zoning itself is meaningless if, due

to GMA legislation, you will not be able to gain approval for your project

because the site lies outside the UGA.

Growth management rules may further require that you prove the

need for the development you propose as a precondition for approval.

For example, you may need to evaluate a site within the context of a

county’s inventory of land sharing the same zoning. How much of that

land is developed and under operation? Can you establish a demand for

additional lands both zoned and developed in the same way? You may

discover that opponents will use GMA rules to prevent new development,

even when zoning is appropriate. While we may assume in most cases

that properly zoned land is implied approval for your development, it is

not necessarily so. You may win the point, but delays and legal fees could

make it less feasible. In comparing one site to another in GMA states,

you may need to limit your site evaluation to available land inside the ex-

isting urban fringe, or be prepared to prove the need for your develop-

ment outside that boundary.

THE THIRD STEP IN MARKET ANALYSIS:

DEMAND FACTORS

Closely related to the site evaluation and the practicality of developing a

specific piece of land is the question of demand. Demand may be a factor

of current zoning, inventory of lands zoned in that manner, and the bound-

aries of an urban area that has access to reasonably priced municipal ser-

vices. It may not be limited to the widely understood definition of market

demand.

Because demand does not necessarily mean the economic version of

demand, we need to be cautious in interpreting statements made by others.

For example, a local politician or antigrowth activist may state that “there

is no demand for a project like this” in the area. What does that mean? In

fact, it could mean that forces are at work to prevent such projects,

whether market demand exists.

Economic demand is a form of demand in which consumers need and

want more of a commodity or type of outlet (shopping center, apartments,

houses, etc.) or, when that demand would be likely to follow if and when

the development occurred. For example, a community may reside 60 miles

from the closest large-scale regional mall. The lack of such a mall right in

town does not prove that there is lack of demand; in fact, were such a de-

velopment to be built, it is logical that shoppers would arrive almost imme-

diately at that destination rather than traveling 60 miles.

The Third Step in Market Analysis: Demand Factors 17

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 17

So a study of demand should include an understanding and study of

market forces and trends, but it is not necessarily so limited. We may face a

more political definition of demand as well. At times, the real agenda may

be to prevent change in any form; in that environment, appropriate zoning

and municipal code provisions may not be enough to gain approval for

your project. This is understandable; development is change, and change is

often resisted for no other reason than because it is perceived as negative

by some people. You may need to include as part of your demand analysis

the local political demand for development. In some jurisdictions, political

demand is at zero. From a development perspective, regardless of the eco-

nomic demand, the project may simply not be feasible because of politics.

This problem is prevalent in many areas, but the range of problems as-

sociated with antigrowth sentiment in residential development (and most

notably against low-income housing) is especially severe. As a matter of

public policy, slow growth policies may ultimately prove the point that

when government tries to control growth, it causes only badly planned

growth but cannot truly prevent it. This problem is aptly described in one

GMA-oriented web site, observing:

Jurisdictions are not accommodating growth because they either

refuse to comply with the law, need political cover from NIMBY

mentality, or lack the resources necessary to provide infrastructure,

amenities and low income housing. During times of high demand,

jurisdictions must do more to accommodate the need for housing.

While the private sector determines the market for housing, each ju-

risdiction determines the availability of land to develop through

comprehensive plans, zoning codes, permit requirements, fees, taxes,

and other costs that may serve to encourage or inhibit growth.

11

THE FOURTH STEP IN MARKET ANALYSIS:

EXISTING SUPPLY FACTORS

The concept of supply is as complex as that of demand in areas where leg-

islation has been drafted in an attempt to control or even to prevent

growth from occurring.

In an economic sense, supply is well understood. It is in reference to

the available properties designated for a specific use. When economic

supply is high, prices will soften because demand lags behind. When

supply is short and demand is greater, prices are driven up. This basic

economic concept is not complex, at least when viewed in its theoretical

definition.

18 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 18

There are three specific kinds of real estate supply: already built, under

construction, and proposed. Each of these has a different level of reliabil-

ity, and the variables should be discounted by the analyst. For example, de-

velopers sometimes announce a project that they do not have tenants for,

only as a way to scare off other developers or to try to attract a potential

tenant in order to drive the development; most downtown office buildings

cannot be built or financed without a committed tenant. So it is a common

practice among developers to announce construction more as a marketing

ploy than as a statement of fact.

In a written market study, the questions of supply and demand may

be limited to a purely economic analysis. If a market study is undertaken

to convince lenders of the viability and cash flow strength in a proposed

project, those economic analyses are quite appropriate. The same is true

when the study is designed to attract equity partners or to gain approval

for tax credits in low-income housing, for example. However, if the pur-

pose of a market study is to determine whether a project is viable both

economically and politically, we need to look beyond the economic ver-

sion of supply.

In residential developments, antigrowth conflict is often associated

with questions of supply. Antigrowth forces may argue that there is an ad-

equate supply of housing and it is not necessary to construct more. This ar-

gument is made even when economic demand is evident. However, the

antigrowth argument continues: If we build more houses, more people will

move here. That means more traffic, higher crime, the need for improved

roads, larger schools, and other consequences of growth. So supply may

come to mean need rather than a purely economic study of whether there

are enough buyers available.

For commercial developments, the question of supply is equally com-

plex. A market study would review buying trends, traffic patterns, logis-

tics, and site-specific questions in order to convince the reader of the study

that a mall, for example, would succeed at a specific site. Included in this

study would be commercial vacancies, affected by shifting traffic and

shopping trends, local and regional competition, and typical rental rates

in the area.

Demand for either residential or commercial developments also needs

to include a study of the trend in net absorption or, in the case of single-

family homes, real estate sales trends in recent months.

Net absorption can be expressed as the square footage of available

space over time, modified by vacancy levels. More specifically:

Net absorption = space occupied – space vacated + space demolished

– construction of new space

The Fourth Step in Market Analysis: Existing Supply Factors 19

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 19

For example, in a particular city, residential vacancies have consis-

tently run below 5 percent; however, in the past two years, several hundred

new apartments have been added to inventory and today, vacancies range

seasonally between 10 percent and 15 percent—a substantial increase. So

net absorption has diminished. The question next becomes, How long will

it take for the market to absorb the oversupply so that net absorption will

improve? This estimate would have to be based on economic and demo-

graphic trends in the area.

In the case of properties for sale, demand is judged based on several

forms of analysis. Checking with local lenders and Multiple Listing Service

(MLS) offices, we find statistics concerning housing sales over the past one

to three years. What is the trend in the inventory of properties? (Inventory

is the number of homes available for sale, expressed in terms of the months

of demand. For example, if 200 homes are sold per month and there are

currently 600 homes on the market, then there is a three-month inventory.)

The trend in inventory levels reveals the demand. If the inventory level is

growing, then demand is falling. The trend reveals the health of the local

housing market.

A related test is the spread between the asked price and the final sales

price for properties. The wider the spread, the softer the demand. In mar-

kets where demand is exceptionally high, spread tends to be low. So again

reviewing the trend, we would analyze demand in terms of whether the

spread is expanding or contracting.

The third important test is time on the market. How long does it take

properties to sell? In a high-demand market, well-priced properties sell

very quickly and, of course, when demand is soft, even bargain-priced

properties may remain on the market for many months. What is the trend?

The answer reveals the level of demand and, more revealing, the trend in

that demand.

Developers hiring outside firms to prepare market studies should en-

sure that the firm is qualified in the particular type of development being

studied. The study should also identify specific factors given the market in

question, rather than relying upon some generalized formula. For example,

many studies are prepared based on markets defined via radius (three or

five miles are common markets in such studies). But this method is not ap-

plicable in most areas. A real market may consist of people living along a

highway as far out as 10 or 15 miles while few other potential buyers or

consumers will be found within a mile-based proximity. The underlying as-

sumptions of the study should be based on the geographical and local fea-

tures rather than on a formula that almost certainly does not apply. For

example, drive time is often a more reliable indicator of markets than ac-

tual physical distance.

20 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 20

One expert has noted that one significant error

is the failure to recognize that a new development will be able to

capture only a share of the market, rather than the entire market.

New projects do not necessarily create new demand. Many ana-

lysts incorrectly assume that if there is sufficient demand in the

competitive market to absorb five lots per month, a new project

will automatically capture all this demand.

12

The same argument applies to economic modeling within the market

study. Broad-based assumptions should be rejected and the market study

based on the local realities and economic mix. This is essential if the study

is to truly identify the market in terms of supply and demand. Such eco-

nomic features cannot be formula-based because every region and munici-

pality is unique in terms of its demographic and economic mix. The market

study should analyze the area, rather than be designed to impose general-

ized assumptions on all areas. A competitive analysis within the market

study should be prepared along similar lines: The market study should in-

volve analysis of specific competitive forces rather than upon generalized

observations about the nature of competition.

How can you determine whether a particular consulting firm uses boiler-

plate assumptions or actually goes into the field and studies the market? One

effective method is to ask to see copies of recent market studies and to com-

pare them. Since many such studies are publicly available and not proprietary

(such as studies prepared for government program clients), a consulting firm

should be willing and able to provide copies of recent market studies.

THE VALUE OF THE FEASIBILITY STUDY

The market study is intended to examine conditions of the local market

and to demonstrate, by way of compelling supply and demand factors, that

the development proposal is justified. In comparison, a feasibility study

questions the financial aspects of the proposed development—tax features,

cash flow, and likely profit or loss—in order to show potential lenders (or

equity partners) that the numbers will work.

While the question of feasibility may be largely financial, it is more than

an accounting exercise. The typical accounting revenue forecast, cost and ex-

pense budget, and cash flow projection is limited to documenting possible

outcomes; the feasibility study, in fact, is far more. It is financial in nature, but

it should be compelling beyond what the numbers reveal. A lender reviewing

a feasibility study should be able to conclude that the risk of financing the

The Value of the Feasibility Study 21

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 21

project is acceptable. Feasibility should not translate to an attempt to show

that there are no risks; a lender or potential equity partner would not accept

such a premise, and, under any standards, such a claim would not be sup-

portable. However, the question of risk is going to be on the minds of anyone

approached by developers for financing or investment purposes.

Feasibility, in its most reasonable definition, is part budget and part

disclosure document. It is properly treated as part of a test of the financial

potential, risk, and financing required. All of this, which is part of the due

diligence process, is aimed at testing the assumptions underlying the pro-

ject. Part of that process—and a crucial part for the lender or the in-

vestor—is identifying risk. This risk may come not only in the most

obvious forms of net loss or negative cash flow. In some instances, a far

more troubling risk may be the possibility that initial financing will not be

adequate to complete the project.

The feasibility study presents a pro-forma version of what is expected

to occur during the acquisition, construction, completion, tenancy, and

eventual sale of the project. What happens if initial financing or equity in-

vestment is not enough to complete these steps? Where will additional

funding be acquired? Of course, the fact that the study attempts to show

how currently known facts might look in the future—in other words, a

forecast—should be accepted as one of many possible outcomes. We

should be aware of an important distinction:

A forecast is not a prediction. Predictions require a leap in logic

and are not necessarily based on known or knowable current in-

formation. A prediction does not attempt to show how the future

relates to the present; it is stated as a fact, independent of and un-

related to what currently exists. A forecast, on the other hand, log-

ically links current information with events that are expected to

occur. In a forecast the future is not unrelated to the world as it

currently exists or will exist; rather, current and future events are

viewed as inexorably linked in some logical way.

13

The difference between these two is central to the theme. Consider, for

example, the point of view of the people who are asked to bring money to

the table—lenders or investors. Because the initial financing is the basis for

identifying potential return to investors (or cash flow to lenders), if that fi-

nancing is inadequate, it presents a very serious dilemma. More financing

will be necessary if the initial lender or investor is to profit; however, the

assumptions all change if and when additional funding will be needed.

With this risk in mind, the feasibility study has to address the financial risk

in very comprehensive terms.

22 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 22

As a planning document, the feasibility study serves as a risk disclosure

summary within the due diligence process. It should follow the market

study. Clearly, disclosure has to be based on market assumptions, so a fea-

sibility study cannot precede a test of the market itself. In the market study,

the big question is, Does it make sense in this market to proceed, given site

attributes, supply and demand, and competitive realities? In comparison,

the feasibility study should ask the questions, Can we afford to build the

project as originally conceived, or do we need to examine costs with mar-

ket and financial attributes in mind?

The market study indicates how the project should be completed in

terms of improvement size and scope (thus, cost). So the assumptions that

go into the feasibility study are based on the market study. That is the en-

tire assumption base, in fact, for studying risks and determining whether or

not a lender can reasonably expect timely payments or an investor can ex-

pect a return and, ultimately, a profit.

If a developer prepares an in-house market study and feasibility study

and then goes forward to find financing, it would be normal for the picture

to be optimistic. And many development firms do, in fact, prepare their

market and business planning documents on their own. However, the real

test of feasibility is achieved when an outside, independent consultant

looks at the same questions objectively. As long as the developer pays the

bill, we may expect a degree of bias and that is unavoidable. However, an

outside consultant should adhere to certain standards and that is an impor-

tant feature of the independent feasibility study. An appraisal firm may of-

fer market and feasibility services but may lack the accounting skills to

prepare a comprehensive cash flow analysis; their emphasis would likely be

restricted to cost/value questions. An appraisal firm with a qualified real es-

tate department that specializes in feasibility studies or a consulting firm

with demonstrated experience in preparing feasibility studies, may be the

best source for preparation of this feasibility study. A word of caution,

however, is offered by a principal in one such organization:

Once you have identified qualified feasibility consultants, there are

other factors that need to be weighed in making the selection. The

most important factor is whether or not the chemistry is right and

the match is a compatible one. This doesn’t mean hiring a firm that

will always agree with you. It means hiring people who have the in-

tegrity to tell the truth as they see it, and at the same time work

with the people in your organization in a team effort that is not ad-

versarial in nature. You must feel that you can trust the judgment

of the feasibility consultant that you hire, without feeling that you

can’t challenge their interpretation of the data gathered.

14

The Value of the Feasibility Study 23

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 23

The feasibility study is most effective when it includes three key fea-

tures. First, the pro-forma number crunching has to be based on realistic

underlying assumptions about financing, costs and rents, and these as-

sumptions have to be critically examined to ensure that they are fair and

accurate. Second, the assumptions used in the feasibility study must be an

outgrowth of the market study. Why? Because “recommendations re-

garding overall project size, unit sizes and mix will drive the overall pro-

ject cost as reflected in the development budget.”

15

Third, a feasibility

study should include a series of metrics so that the reader can better un-

derstand the cash flow statement. This could include time value of money

calculations such as the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) or Present Value

calculations. Other metrics that examine return for both investor and

lender should be examined (such as cash-on-cash on both leveraged and

unleveraged bases; loan-to-value; and debt service coverage ratios). Fi-

nally, a competent analyst will include sensitivity analyses that show how

small changes in underlying variables (i.e., capitalization rate) may result

in large changes in project value.

Feasibility cannot be studied in a vacuum but should serve as an out-

growth of competitive analysis as well as an understanding of supply and

demand locally; if the market study shapes the development as it should,

then the feasibility study shapes the financial questions in a meaningful

way, including risk assessment as well as acquisition and development cost

levels and cash flow.

One possible outcome of the feasibility study is the conclusion that, in

fact, the project as originally conceived does not work out financially. If the

investment cost is too high based on potential cash flow, the conclusion

may be that the whole project will have to be scaled back. In the most ex-

treme case, the idea may have to be abandoned and the land used for other

projects (or if land has not yet been acquired, the whole project would be

abandoned). In those instances, it is far less expensive to pay the cost of a

market study and a feasibility study, than it would be to attempt to finance

the project. The cost of proceeding when the numbers do not work would

be far greater for all concerned.

WHO USES MARKET ANALYSIS?

Should market analysis be performed only as a means for obtaining financ-

ing? The market study and feasibility study are essential for raising money

for a project, but is that the end of the process?

In fact, market analysis and the output obtained from it are valuable

24 THE ESSENCE OF ANALYSIS

ccc_kahr_ch01_1-28.qxd 8/3/05 11:50 AM Page 24

planning documents. These can and should be utilized throughout the

project by architect, engineer, and the project planning team. In develop-

ing the raw material, the individual or firm preparing a study considers

population, income, employment trends, commuting and traffic patterns,

and more. But the market and feasibility studies should evolve beyond a

summary of raw data if they are to be effective. Many ineffective reports

end up gathering dust in the project manager’s office, because they are not